- In the past you have gone beyond the bounds of your art of Kyogen. Now I hear that you are working with an Italian and a Swiss comedian to create a new kind of theater.

-

This project is actually an outgrowth of efforts by my son Akira [Shigeyama

(*)

]. Twenty-five years ago Akira took a year off from [Kyogen] performance responsibilities and went to Europe. From a base in Spain, he went around seeing all kinds of theater, old and new, and what especially caught his interest was the comedy theater called Commedia Dell’Arte performed mainly in northern Italy that has a very similar comic style to Kyogen. Akira went to performances of Commedia Dell’Arte numerous times and got to know the performers. From that time he got the idea that he would like to perform with them some day and he kept that idea simmering all these years. He also kept in touch with the performers. A few years ago I also went to visit their theater and studio in Switzerland and I did several Kyogen performances while I was there. At that time we performed on the same stage, but it was alternating performances of Commedia Dell’Arte and Kyogen, which was still far from what Akira was dreaming of.

Now for the first time we are doing a collaboration where we perform together in the same work. Rather than saying that we found a point in common, I would say that we stuck together with a determination to create a production together. This is called the 3G Project. 3G stands for “3 Great Performers,” implying Alessandro Marchetti of Commedia Dell’Arte, the Swiss clown Dimitri and myself representing Kyogen, but I would say that it could actually mean “3 geegee ” (meaning in Japanese “3 old men”). I am 85, and the other two are 78 and 73. I want to see us to work in a direction these three old men can create works and perform together on the same stage.

But, that said, at our age the time we have left isn’t long (laughs), so those around us have been anxious to see it done quickly. As a result we did experimental performances at Verbania in Italy and then in March in Kyoto and Tokyo. In these performances, Dimitri wasn’t able to take part, but Akira prepared a Kyogen version (Japanese) of the comedy Three Tobacco Containers from the Commedia Dell’Arte repertoire and Akira and I performed it in old Kyogen style Japanese while Marchetti and his wife Luisella Sala performed in Italian. I would say a line in Kyogen style Japanese and Luisella would answer in Italian.

From now on we three old men are going continue climbing this staircase, first in three steps then in five. It will by no means be a process of reviving old plays. We will surely be using old traditional devices and methods as our working base to create contemporary plays, and hopefully plays for the future. I’m sure that Marchetti and Dimitri are thinking the same thing. Because the audience is people of today. Our approach is to use a variety of styles and contemporary stage technology and know-how to create contemporary stages. - What is the meaning of initiating this “3G Project” at this time?

-

Kyogen is an art that has been handed down from about 550 years ago, and has been performed constantly down through these centuries. However, the Commedia Dell’Arte art was lost at one point and only revived through the efforts of Marchetti’s grandfather based on the remaining written records he was able to find. And Marchetti has carried on that revived tradition. Dimitri is one who has been working to open up new artistic areas based primarily on the circus clown tradition, and he is already recognized internationally as an artist. We speak different languages and come from different historical backgrounds and different societies, and these factors have naturally produced differences in our styles of stage performance. Nonetheless, theater is universal.

Furthermore, unlike in the past, the world we live in today is one in many ways. We are able to fly anywhere around the world today, transmission waves spread information everywhere and even new influenzas spread globally. In such a world, if we form our own separate sect and do our own separate styles of theater, they will end up being performed only within the confines of our separate regions and ethnic groups, and eventually become narrower and narrower in scope with the passing of time. If theater is a universal art form, won’t the future be one in which where people of different backgrounds collaborate to create new types of theater? We want to try to work in that direction and spread that spirit while we’re still able to perform.

Also, when you think about it, comedy is an area of theater that is well suited to collaboration. In all parts of the world, the scenarios of comedy are relatively simple and the number of characters involved in a comedy play relatively few. What’s more, the characters appearing in comedy are quite clear nature. There are men versus women and masters versus servants. For example, in Kyogen we have the common “Taro-kaja” character who appears as a servant of the lord ( daimyo ) of the local fiefdom. In this case the lord is always trying the servant Taro-kaja to do some kind of work and the Taro-kaja is always wants to slack off and be lazy. This situation is the same in Kyogen and traditional Italian comedy. In the case of a man vs. woman Kyogen, the husband is always lazy, a drinker and lecherous. It is the same in the West too. The wife, in contrast, is eloquent and resourceful. In Kyogen this is called the wawashii (noisy) woman. She chides the husband and tries to get him to work. I believe that this man-woman relationship, husband-wife relationship is universal in East and West, in olden times and today.

Another common characteristic of the comedy theater of the East and West is that it deals with the lives of the common people. You don’t see great figures appearing in comedy and you also don’t find bad characters either. All the characters are good in nature. And there are no fools either. The clown is traditionally a character in which some weakness of human beings are exaggerated, but they are not fools. The daimyo lords as they appear in Kyogen are easily manipulated by their servants almost as if they were fools, but in fact they are acting politicians who have achieved their status through actual accomplishment as such. But all humans have some weaknesses. For example, they may be lacking in knowledge. Those are the qualities that are exaggerated to create characters in a comedy. There are many comedy plays built on this formula in both the Kyogen and Commedia Dell’Arte repertoires.

Now we live in an IT world overflowing with information that makes it easier to get to know and understand each other, and this should surely make it easier than in the past to create things together. - Do you have a stronger feeling now that you can transcend national and language boundaries to work together?

-

Yes. And that feeling is getting stronger with each [3G Project] performance.

I, of course, and Akira as well don’t speak any Italian, and they [the Marchetti and Dimitri] don’t know any Japanese at all. What’s more, in the plays you have moments when we ad lib. Still, when our lines are finished they know when and how to answer [despite not understanding the actual Japanese]. That is because “language” is inherently something that communicates not just “word meaning” but the “will and intent of the speaker.” For example, there are cases where the will of the speaker is communicated even if the specific word meaning of what he/she says is not. Taking this further, language communicates religion and philosophy. And that is why we are able to work together [despite speaking different languages], I believe.

However, in my view, what many Japanese today don’t believe words until they see them in print. I feel that they depend too much on the written word today. - Does that mean that people are depending too much on the communication of word meaning rather than the communication of will or intent?

-

Yes. I believe that today language has become flat like a board [without accentuation] and that is resulting in a tendency toward the communication of word meaning only.

For example, consider the words “I love you.” This expression is made up of three linguistic elements, and the will of the speaker is communicated differently depending on which of those elements the accent is placed, isn’t it? If the person accentuates the “I” and says, “ I love you,” it means “I don’t know if you love me, but I love you.” If on the other hand the “you” is accentuated in saying, “I love you ,” it means “It is you and not any other that I love.” And in Japanese, where the verb can stand alone without a subject or object when the latter are clear in context, if you are alone with the one you love, you can simply say the verb conjugation “ Aishitemasu ” [(I) love (you)]. Thus, the simply expression “I love you” can take on completely different nuances of meaning [will/intent] depending on where the accent is placed.

But in what I call “flat board language” the same stress is put on all words evenly without accentuation. In that type of flat communication, even if you understand the word meaning of “I love you,” it doesn’t communicate to the listener what kind of love it is. - Is your form of “communication of will” one that has been nurtured in the Kyogen tradition?

-

Both Kyogen and Commedia Dell’Arte are oral traditions that have been handed down verbally from master to apprentice, generation after generation. The master says a line in old Japanese such as, “

Kore wa konoatari ni sumaiitasu mono de gozaru

,” (I am a man residing in this area) and the apprentice recites it in the same way. It is an oral process that doesn’t use the printed word. Also, in Kyogen this teaching begins when the apprentice is still a child and before they begin to use the right hemisphere of the brain. I don’t even remember my own first stage performance because I was just a child of 2 years and 8 months. My training must have begun when I was about 2.

In my case my master was my grandfather. He would sit down facing me in a room and there would be some sweets in between us that I could eat when I got the lesson right (laughs). It is the same method used in training a monkey. It is a method that makes learning relatively quick. The movements are also learned by copying the movements of the master until you memorize them. In this method the forms and lines are learned first and then the meaning and expressive content come later.

This method is the same for all the traditional Japanese arts, from Kabuki to traditional Japanese dance. The European methodology may be different, but I believe that the tradition arts have been passed down in the same sort of way. There are similarities in this aspect, too. Whether we perform in Japanese and Italian there in meaning conveyed by the sound of the spoken word. And actors are by nature and by their training very sensitive to spoken language. Especially to rhythm and interval in the delivery of their lines that we call ma in Japanese. When we perform together in 3G, the interval ( ma ) in delivery is very clear to each other [even though speaking in different languages]. The reason for this is the distinctive way an actor ends the last words of a line, and that is what creates the interval. In short, there are special ways of ending lines, and I feel that these are the same in Japanese and any other around the world. It is a kind of verbal magic. The first requirement of a skilled actor and a good play is that this verbal magic that is not based in the written word comes from the mouths of the actors. - Is your desire to communicate “the power of words to convey will” part of the purpose you bring to the 3G Project?

- That is a part of my purpose. I believe that the Japanese have to see more live stage performance. We are now engaged in a program called the “Kyogen Delivery Service” that takes Kyogen performances to schools to be performed in their gymnasiums or theaters, but in recent years the number of theses performances have decreased. Thirty or forty years ago we were doing ten school performances or so a month. Now it is my grandchild’s generation that is doing it and that number is smaller. One of the reasons for the decrease is of course Japan’s decreasing birth rate. There are also economic reasons, I believe. But there is also the problem of parents complaining when their children’s schools plan things like live performances Kyogen or Noh theater or music. They say, if the school has that kind of time they should have the children studying to pass entrance exams. The mothers call it a waste of time. But I want to see the children being exposed to live stage performances more so they can experience power and appeal of words and the inherent function of language.

- Since you have mentioned school Kyogen, I have heard that your Shigeyama family has long been very dedicated to the spread of Kyogen through school performances.

-

During the Middle Ages Kyogen was like the television dramas of today, in that they presented new stories every day and they often included seedy songs. In short, it was contemporary theater. However, in the Edo Period (17th to mid-19th centuries) Noh and Kyogen were labeled ceremonial entertainment and came to be performed only during ceremonies of the samurai class that dominated society. So, Kyogen was almost never performed except in combination with Noh performances. In its place, Kabuki became the contemporary theater that provided entertainment for the common people. Even after the Meiji Restoration at ended the Edo Period, the concept of Kyogen as a ceremonial theater continued, and breaking that rule of performing Kyogen only with Noh was considered a degradation of the art.

Up through my grandfather’s generation, Kyogen performers weren’t even permitted to go see Kabuki plays. They were told that if they went to see such vulgar plays as Kabuki it would degrade Kyogen. My father says that when was a child he used to disguise himself to go see Kabuki. During that era when Kyogen could only be performed with Noh, my grandfather defied that precedent and would perform Kyogen anywhere and anytime there was an opportunity. My grandfather was what we called a “high-collar” of that time, he liked Western style suits and I hear that he was the first among the Kyogen actors of Kyoto to eat beefsteak. He wasn’t one to cling to the old for its own sake. If he received an invitation, he would perform Kyogen, even if it was as a side-event at a garden party. The other Kyogen actors who didn’t like that attitude used to ridicule him, saying, “Shigeyama’s Kyogen is like tofu (bean curd).” - So, the phrase “ Tofu Kyogen” that is now part of the Shigeyama Family Pledge was actually a phrase of ridicule at first.

-

That’s right. It was a term of ridicule. There is the saying, “It you don’t have anything to eat with your rice, you can always have cold tofu or boiled tofu with it.” Well my grandfather’s critics started saying, if you don’t have a sideshow [for your party], you can always call on Shigeyama and have him do Kyogen for you, his Kyogen is just like “tofu.”

I don’t know if my grandfather had a cynical streak or if he was just practical or resolute or what. He’d say, “I’m happy to have them call our Kyogen tofu.” Cold tofu can be a humble side dish for the family table or a delicacy at an expensive restaurant, and it is very nutritional. Depending on the flavorings you add, it can be used in a variety of delicious dishes. And everyone likes it. So he started saying that our family’s Kyogen should indeed be like tofu in that sense. After he kept saying that for a while it became something like a Family Pledge for us and people started referring to it as “tofuism.”

Underlying our current 3G Project is also my grandfather’s kind of “tofu philosophy” that believes Kyogen shouldn’t cling to the old quality standard of only being performed together with Noh. There are some people who call Kyogen art, but personally there is no word I dislike more than art. It is fine with me if other people call our Kyogen art. But, I myself never intend to perform so poorly that I have to call my stages art (laughs). I’m still an unskilled performer, but if I thought that my stages were so poor that I had to call it art in order to feel justified in showing it to people, then I’d rather quit altogether. What our tofu Kyogen is, is Kyogen that doesn’t need the label of “art.” - So the fact that you are able to undertake so many new forms of stage performance is actually an extension of that “tofuism” philosophy.

-

It is probably because I was raised in that kind of family and performed that kind of Kyogen that I am able to work as I do today. If it were only my own will alone, these various opportunities would probably not have come my way. Since people know that most Noh and Kyogen performers don’t perform with other artists, the outside offers do collaborations tend to come to the Shigeyama family, I believe. In July I will be directing a production of the opera

Turandot

at the request of conductor Michiyoshi Inoue. I don’t now much about opera, and the only music background I have is singing in our elementary school chorus, so I can’t even read musical score. So, some of my friends laughed and said jokingly that at the idea of a Kyogen actor like me directing opera is indeed “real Kyogen [comedy].”

In fact, however, traditional Japanese performing arts and opera actually have many points in common. For example, during an opera aria, the singer faces the audience to sing, and there is applause when the song is over. In real theater something so ridiculous could never be, could it? But in Kyogen the actors face the audience and talk to them in the same way, and so do actors in Kabuki. This is a point in common with opera. Another point is the artistic license to use expediency when convenient. They have the freedom to change the conventional order of things if that makes the play flow more smoothly. And the audience goes along with it.

Another thing they have in common is illogical developments that would otherwise be considered absurd. In representative Kyogen plays like Busu and Boshibari the Taro-kaja and Jiro-kaja characters do something bad and run away from their lord. The lord chases them off into the wings shouting, “You can’t get away with that!” and the stage just empties at that point for the intermission. When we perform this at schools the children will come up and ask us, “Hey, Mister, did the lord catch them or what?” We’re in trouble then because there is really no way to answer that question (laughs). There is no answer written in the script, and our masters never told us what happened after that. There are also many Kabuki plays that don’t really reach a conclusion and just end with the words, “We will end it here for today.” That’s more absurd than Becket’s [theater of the absurd]. That is another thing the opera and traditional Japanese theater arts have in common.

I know Kyogen and Noh and I like Kabuki and have worked together on stages with Kabuki people, so I have many friends there. It means I have the various drawers. I have a drawer of contemporary theater friends and a drawer of friends in lighting and sound, so I can say, “For this scene I will open this drawer for help,” and learn from their knowledge and ideas. Drawing on these different drawers I have is the way I create stages as a director. - What have you been asked to do for Turandot ?

-

Of all the forms of theater, opera is the one that requires the most money to produce. But today, the corporations and countries that have supported opera in the past have no money. In order to do opera under these conditions, you have to cut costs. But, if you cut costs with the music or singers you can’t have good opera. So, if you are going to cut costs it has to be in the set, the costumes, the makeup and lighting. And isn’t Kyogen what you have when you reduce all of these aspects to the bare minimum? Kyogen has no set or stage art, and as for props, one fan in the hand of a Kyogen actor serves as everything from a plate to a door to a carpenter’s saw. It only takes a cast of four to do a 2-hour Kyogen performance, so thinking of it in that way, there can’t be a more “ecological” and cost-efficient type of play than Kyogen (laughs). And this time the opera I am directing is a truly “eco opera” with no set.

Still you have the 80-person orchestra, which too large to fit in the orchestra pit of a small theater. So, they have to be brought up on the stage. If the orchestra is placed at the front of the stage, however, you won’t be able to see the [soloist] singers, which means the orchestra has to be positioned on a raised platform at the back of the stage. That makes for a shallow stage for the actors and singer and eliminates the possibility of using drop curtains. Without curtains, the entrances and exits of the actors will all be visible to the audience [like they are with a Noh/Kyogen stage]. So what could we do but use the devices of the Noh staging?

Turandot is supposed to be a story set in China, but in fact the setting is the European image of the Orient at that time. From our perspective it is hard to tell what China it was, so there was no reason to confine ourselves to the Chinese setting. Instead of the makeup used in Peking Opera, we could use the makeup of Kabuki with similar effect, and the costumes could also be Kabuki costumes. In opera the chorus plays a very important role. In the practical European approach they make the chorus palace guards or maids-in-waiting and give them individual roles as well. They also assign roles according to age. In that case their costumes have to be different for the different roles they play. In Noh, the chorus equivalent is the Jiutai performers, and they are all clothed in the same plain crested kimono. So for this opera, I thought that it would be OK to costume the chorus all in the same gray and white kimono, while some extra decoration could be added for actors with specific roles. In that way they can be cast either as guards or maids-in-waiting. I don’t now if it will be successful, but at least it will be easy for the audience to understand. - You are thinking of new projects one after another. In February you did a completely new “Su-kyogen” performance with your older brother Sensaku, in which you both performed sitting for the entire play.

- That was quite an adventurous new attempt, but that response has been rather good. I am having trouble with my knees lately and it is getting difficult for me to do the standing movements of Kyogen. My brother is 90 and most of the time he needs someone supporting him or a standing for the standing movements. But his mind is still clear and you don’t forget the lines you learned when you were young. We want to continue doing Kyogen, so what do we do? I thought we could do a play together if we didn’t have to move, and that led to this plan. It went well and next February we are going to a second Sensaku, Sennojo production.

- Most people think about retiring when they have trouble with standing performance, but you turned that disability around and thought about what you could do next.

- That’s right. I am always thinking about what I can do next. I like doing that. I guess it is just my nature.

- Do you also take on new [contemporary-written] Kyogen plays because it is something you like?

-

I have done a lot of new Kyogen plays. I have even written one myself, but the results are usually boring if it is written by someone who knows Kyogen too well. If you know Kyogen too well, you become confined by the framework and conventions of Kyogen. The chances of a good result are few if you are just trying to fit new themes of motifs into the existing framework of Kyogen. In the past there were thousands, tens of thousands of new Kyogen plays written and discarded as no good, and the ones that survives after several hundred years are the repertoire of traditional Kyogen that we have today. That is why you won’t get good new plays unless you transcend the existing framework of Kyogen. And that is why most new Kyogen plays may be performed once or twice and never performed again.

There are two exceptions that have been successful, however. One is Susugigawa by the playwright Tadasu Iizawa. This is a play Iizawa wrote based on a French story for the theater company Bungakuza. It was not written for Kyogen originally. But I asked for permission to allow us Kyogen actors to rewrite it for Kyogen. Traditional Kyogen was mostly a product of ad lib by the actors, and I believe Susugigawa was successful because we did it by that same process.

The other successful new play I would cite is Hikoichi-banashi by the playwright Junji Kinoshita. This was also written originally with no intention of it being used for Kyogen. But, there is a scene in which Hikoichi jumps into a river, which would be very difficult to stage in a realistic modern theater production. But in Kyogen it is easy. If the Kyogen actor simply does a swimming motion, that in itself turns the stage into a river [in the audience’s mind]. So, bringing Kyogen conventions to the staging of this play made successful. - The Kyogen trilogy written by philosopher Takeshi Umehara was also interesting and drew a lot of attention. The first work of that trilogy, Mutsugoro , brings in the new theme of environmental destruction by telling a story of the small marine animals being displaced by land reclamation projects that are actually going on.

- It is something that could only have been written by Umehara. We could never have thought of a story like that. It could certainly never have been written by a scholar of Kyogen. Umehara is one who has studied the philosophy of humor, and I hear that he did his graduation thesis on [Henri-Louis] Bergson. So he is very much interested in comedy, and I hear that he is a big fan of Japanese traditional Rakugo comedy. That is why he was selected when the National Noh Theater planned a program of new Kyogen. But the work Umehara wrote was so long that the resulting script was so thick it would have taken about five hours to perform by my estimation. I took that and reduced it to about one-third its original length.

- The second work in the trilogy, Clone Ningen Namashima (Human Clone Namashima), is about baseball and the play is full of clones of popular Japanese baseball heroes.

- It was very interesting. When we did Namashima we used a flute to make the sound of a baseball flying through the air. When I was working on directing it, I told the musicians where I wanted sound effects and left it up to them what sounds they would use. They all made suggestions such as where to use taiko drum and where to use Otsuzumi . They got going like that and finally we had the flying flute sound (laughs). And, since the musicians performed in [informal festival] happi coats and headbands, in the past I, as director, would have been forced to quit Kyogen in disgrace.

- These new works take difficult contemporary issues like the environment, cloning humans and war and present them in a clear and appealing wrapping of comedy. Watching these successful new Kyogen plays, your claim that Kyogen is a contemporary art really ring true.

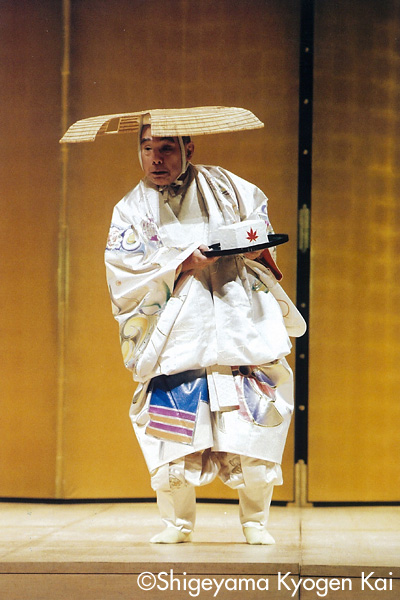

- These new works are indeed interesting. But, many of them are on topical themes of the day and will therefore be difficult to perform again and again over time, I believe. Recently, one new work that has been performed repeatedly and become part of my repertoire is Yokai Kyogen by the novelist Natsuhiko Kyogoku. There is Tofu Kozo and Kokuri-banashi , about a battle of deception with a fox. I don’t know of any other author who could have brought the world of ghosts and specters to Kyogen. These are works that only could have been written by someone like Kyogoku who knows ghost literature so well. We have performed Tofu Kozo more than 20 times.

- With the 3G Project and new Kyogen works, we will be watching your future activities with great interest.

-

I will continue to work with an “everything goes” attitude. But one thing I want to stress is the fact that Kyogen is contemporary theater. This is true for Kabuki, Noh, Kyogen and Bunraku are not old forms of popular entertainment of the common people of olden times. They are contemporary theater using traditional conventions and methods. They are contemporary theater. Whether it is the bureaucrats or the scholars, they describe Kyogen first of all by talking about Zeami and the writer of the original Noh plays and then say that Kyogen was the plays done in between Noh performances. In Kyogen there are several schools, including the Okura school and the Izumi school, which have been handed down over the generations. But to the audience this means nothing. Even though the famous works of opera and ballet were written long ago, they aren’t presented as the “Old traditional arts of Europe,” are they? But now Noh and Kyogen have been designated by UNESCO as World Heritages. I said that if you do that Noh and Kyogen will die. I protested fervently, saying, “Don’t make us traditions with one foot in the coffin.” Now we have to work even harder to show that Kyogen is a contemporary theater.

Anyway, thinking of new things to do as we go along is fun. Maybe that’s why I don’t seem to get old. If your work makes you young and you can enjoy a good drink at the end of the day, who could ask for more?

Sennojo Shigeyama

Cross-over Kyogen master Sennojo Shigeyama’s

quest for a new form of global comedy theater

Sennojo Shigeyama

Sennojo Shigeyama is a Kyogen actor and director born in Kyoto in 1923 as the second son of the late Sensaku Shigeyama III. He was apprenticed under his grandfather, Sensaku Shigeyama II. He inherited the name Sennojo II in 1946. In 1948 he broke the Noh/Kyogen world taboo against working with artists from other arts genre and did radio dramas with other artists. He participated in the theater movement to revitalize Kabuki and other Japanese theater forms led by the director Tetsuji Takechi. He has performed in Kabuki, Shingeki (Modern Theater), films and TV dramas and earned a reputation as the Maverick of the Kyogen World. He has also directed revival productions of eliminated Kyogen pieces and new Kyogen plays, opera and Shingeki in his highly diversified activities. His son Akira and grandson Doji are also Kyogen actors.

Interviewer: Kazumi Narabe, cooperation: Miho Project Ltd.

* Akira Shigeyama

Kyogen actor. Born in Kyoto in 1952, he apprenticed in the Kyogen art under his grandfather, Sensaku III and his father, Sennojo. He leads the theater company Noho Gekidan with American Jonah Salz, a professor of Ryukoku University and has performed Becket and English Kyogen overseas as well. He devotes efforts to the staging of new Kyogen plays and reviving old plays no longer part of today’s Kyogen repertoire. He has also directed opera.

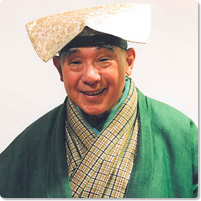

3G Project experimental performance

“Commedia Dell’Arte and Kyogen”

Mar. 23, 2009 at Kyoto Art Center

Mar. 24, 2009 at Istituto Itariano di Cultura di Tokyo

Sennojo Shigeyama (left), Akira Shigeyama (center), Alessandro Marchetti (right)

© mihoproject

©mihoproject

Su-kyogen (Kyogen performed in a sitting posture)

Shuron

Sensaku Shigeyama (left), Sennojo Shigeyama (right) ©Shigeyama Kyogen Kai

Yoka Kyogen

Tofu Kozo

Written by Natsuhiko Kyogoku

Directed by Akira Shigeyama

©Shigeyama Kyogen Kai