- Although this does not pertain only to the shamisen (*1) , the trend among artists in the Japanese traditional arts definitely seems to be toward increased specialization in their arts. In the case of the shamisen, people who do nagauta (*2) (long narrative poems with shamisen accompaniment) stay within that specialty and people doing minyo (traditional folk song) specialize only in minyo . The boundaries between the musical genre are firmly established and very few artists cross those boundaries in their musical activities. I believe that makes you unique, in terms of your broad ranging of activities.

-

Ever since I became a performer, I have always had the idea that I wanted to be “a Japanese shamisen player” in the broad sense of the term, so I have never been very concerned about or conscious of genre. But that said, since I am a shamisen player, I believe that the shamisen should not lose its Japanese and its Edo Period flavor.

There are four main pillars to my musical activities. The first is hauta (*3) as classic traditional shamisen music. Next is the regional songs usually called minyo. That is a name I don’t like, and I prefer to call it chiho uta (regional songs. The third is Risougaku (*4) which is an attempt to make new shamisen music based on the idea of minyo as Japanese folk music. And although I say new, it is still based in tradition. The fourth is the “ATAVUS” group that I perform with as a contemporary, living form of folk music.

And, since I also compose and perform shamisen music as contemporary music, I believe that you are right in saying that in the shamisen world I must appear to be someone engages in a lot of different activities. - I don’t think there are any other shamisen artists in your generation who are engaged in activities like yours. What made you think to cross the boundaries of the different genre of shamisen music?

-

The biggest reason, I believe, is my strong desire to play the shamisen. There is a 17th century book called the

Shichiku shoshin-shu

that tells how to perform on the shamisen, and reading it one gets a sense of the surprise with which the Japanese first encountered the shamisen. It appears that it had been imported as an instrument separate of any knowledge of how it should be played. So, I believe that the people at that time were like children with a new toy in their search for how to play it. And I want to play the shamisen with the same spirit the people at that time must have had. If I can do that the shamisen can be more alive as an instrument. I want to overcome the image of shamisen music as old music and make it more alive in the present. That is the feeling that started me on my multiple-genre course.

Also, since in traditional shamisen music the shamisen is always in a set with the song, I thought the instrument could also be played separate from song. I had the desire to separate the shamisen from song so that it could be played more freely. - It would seem that this approach you have to must be related to your original encounter with the shamisen or your early training with it. Can you tell us about your first encounter with the shamisen?

-

I didn’t really begin learning the shamisen at a very early age. I was about 11. Actually, I wanted to learn the guitar, but I grew up in a small town where it wasn’t easy to get a guitar. My hometown was a harbor town on the Tone River that still had a good number of geisha and traditional entertainers, so the shamisen was a familiar and accessible instrument. And, since it was also a stringed instrument, I thought it might be just as good—even though it didn’t have as many strings (laughs).

Once I began learning the shamisen, I would go to my teacher in town for lessons every day. I already had a reputation at the time as a bad boy in town, and my teacher apparently thought I would quit before long. So the arrangement was that I had to take the fee to him for each lesson. I remember that at the time it was 25 yen per lesson, so I would get the money from my mother or someone would give me some spending money and I would take that to go for each lesson. They say I never missed a day, so I must have really liked it. - What types of pieces were you learning at that time?

- I learned pieces from all of their repertoire, including Tokiwazu songs, Kiyomoto songs and nagauta. I was taught minyo and hauta. It seems that from the time I was a child I was singing adult songs without even knowing the meaning of the words or emotions. I was often told that I was singing like a seasoned geisha, even though I was just a child. It became a sort of trauma for me, and to this day, whenever I see a TV show where they have a child singing adult songs, it depresses me to watch it. I guess that is proof of how much of a trauma it was for me.

- But if people were saying that you sang like a seasoned geisha, it must mean that you were quite good at it.

- It seems that I was (laughs). I was often up on stage playing and singing at festivals and the like.

- And did people call you shamisen child prodigy? Were you famous at the time?

-

Yes, I was famous (laughs). Like many parents I guess, my mother saved posters from my performances, with things like “Child Prodigy” written on them in red ink (laughs). Seeing that made me feel her maternal affection. By the time I had reached middle school, I had decided to become a professional shamisen performer, and I moved to Tokyo, with my family in tow. Usually, when a young person makes that kind of move, it is to study under some specific teacher in an apprenticeship where the teacher looks after you. But I was the reckless type and I just picked up and moved to Tokyo with no certain plans. But it happened that in the neighborhood where I settled there was a nagauta teacher named Yoshie Kineya and I was able to enter an apprenticeship under her.

As a teacher, Yoshie sensei [teacher] had a very liberal approach. She used to take me to the nearby art museums and historical museums in Ueno and have me write reports on the things I saw. Since playing the shamisen is a physical act, anyone can play the instrument to some degree if you train the right muscles. But if you can’t go beyond that and find a certain atmosphere or feeling when you are playing a piece, it is nothing more than a physical exercise and, thus, meaningless as performance. So, she often told me to go out and find true art, things of true beauty, and learned to appreciate and be moved by the real thing. I feel like I was the luckiest person in the world to have met her and to have been able to spend those impressionable young years under her guidance.

I studied nagauta under Yoshie sensei until I was 18 or 19, and around that time I was getting jobs accompanying dancers [of traditional Japanese dance] and was feeling the desire to reach a level where I, as a musician, could perform on the same artistic level with a dancer and achieve a form expression that involved give-and-take between the dancer and the musician. That made me decide to quit nagauta for a while, and so I left Yoshie sensei’s studio.

Up until that point, I had been guided by the desire to properly instill in myself, in my ears the distinct scale of the constituted the true “shamisen sound,” and to the degree that I hardly ever listened to [Japanese] popular music or folk music, not to mention foreign music. The shamisen tonal scale has half tones that are slightly different from foreign music, in a way that you might call narrower or more nuanced. So, I thought that if I listened to other types of music besides nagauta I wouldn’t be able to achieve the true shamisen sound when I played.

That tonal nuance is the thing that I find most difficult to explain to people from other countries. With the shamisen we call the points where you press the strings down to get the different notes “ kandokoro ” (literally “sense points”) and they are constantly changing, or fluctuating, with the music. You could say that the sound is determined by a balance with the sound that has come before it and the sound that is to come next, or you could say that the kandokoro is not the same every time—in other words not a specific pitch—but, it is like each note has a “sound character” ( onkaku ) that defines it. It is a sound that, when you play it, the listener gets an intuitive sense of the feeling intended. That is the unique aspect of the shamisen that I wanted to instill firmly in myself back in those days. - After you left Yoshie sensei’s studio, what did you do?

-

While continuing to do nagauta, I became a live-in apprentice with the minyo artist Fujimoto Hideo the 1st. At that time I took a combination of my grandfather’s [given] name and my teacher’s name and began performing under the new name Fujimoto Hidetaro. But at the age of 24 I left the apprenticeship at the Fujimoto home and worked for about two years doing recordings for commercials and popular music (

kayokyoku

). At that time it had become popular to use shamisen accompaniment for popular songs, and I sometimes found myself playing the shamisen in the orchestra pits of places like the Tokyo’s Kokusai Gekijo and the Nichigeki Hall. I have fond memories from that period.

At the age of 26 I went independent under the name Honjoh Hidetaro. What was your intention in going independent under the name Honjoh Hidetaro? Did you have an image in mind at that time of becoming a shamisen performer active in multiple musical genres?- In my case, it was a situation where I was forced to go independent. At the time, our shamisen world had no family-line [school] system, so I thought that as long as I had to go independent, I would start my own family-line school of shamisen music under the Honjoh name. It was partly the impertinence of youth and I regret it now, but I thought that if I created my own family-centered school, apprentices would come and support my musical activities and make it possible for me to pursue the kind of shamisen music I wanted more freely (laughs). So, I started a new genre of music that I called Risougaku and gave myself the new name Honjoh Hidetaro so I would be the founder and head of a new family-centered school. I regret that now.

Usually, when you start a new school of music like this under a new name in the hogaku [Japanese traditional music] world, you have a commemorative celebration and concert series, but I didn’t do any of that. I thought there would be time for that once my activities took some definite shape [style], and in fact, for a concert I had celebrating the tenth anniversary of my establishing the Honjoh name, master artist Fujimoto Hideo came to perform with me. I will never forget the thrill of that moment.- Did any apprentices come as you expected?

- They didn’t, because nobody knew what was going on (laughs). A year after I quit [the Fujimoto school] and went independent, I had “Honjoh Hidetaro no kai” concert at the Yomiuri Hall [in Tokyo], and for that concert I composed and performed a piece based on music of the Silk Road called Camels and Ships , inspired by the idea that the shamisen had originally come to Japan via the Silk Road and the sea routes from Persia. The piece was like a story of the journey of the shamisen to Japan by camel and ship. That was at a time before the Silk Road became a popular subject and destination for the Japanese due to a series of NHK [national television] documentaries. After that did concerts every year at [Tokyo’s] Kosenenkin Hall and Nihon Seinen Hall, and this continues today.

- Those are big halls. Were you able to get enough audience to fill them?

- They were sell-outs. I found out that I had a large number of fans from my days with the Fujimoto school (laughs). In my Fujimoto days I only performed in the student recitals but whenever I performed the hall was always full, and after my performance it would empty again.

- I guess you were an idol, weren’t you (laughs).

- I guess so (laughs). Partly because I was the youngest performer in the minyo scene at that time. Among the shamisen genre at the time, the minyo performers wore the most flamboyant kimonos, but I didn’t like that. And, partly because I didn’t have the money, I made it my style to wear a plain [pattern-less] kimono with a pure white Kenjo [Hakata] obi sash and white zori sandals. And when I did, that style became popular among my fellow performers as well.

- And you began composing from the time you first went independent, didn’t you?

- I never really studied composing, it just came out naturally.

- Until the influence of Western music came into Japan, I don’t believe there was no separate profession of composer in Japanese traditional music. The musicians of old both composed and performed. And what remain among their works is what we have the classics today. But today, performing and composing are separate professions and it seems that there are few like yourself who actively compose and perform.

- For me, especially with the shamisen, I have a sort of basic distrust of composers. When someone who specializes in composing writes a piece for shamisen, I feel that something is amiss. They don’t understand what it means for a piece to have the [fluctuating] “sound character” I mentioned earlier. As in Western style composing, people put notes of specific pitches together into a melody, I feel. In the case of the shamisen, because there is a “sound character” each piece has its own distinct pitch, and making sounds of those distinct pitches fit together in a piece is in itself a very difficult thing. If a piece is written with notes in the same way as a koto [Japanese harp] or shakuhachi [bamboo flute] piece, the shamisen doesn’t resonate at all. For me, the biggest problem is when the shamisen doesn’t resonate, and that is why I feel that I have to compose pieces myself. Because I want to bring the shamisen to life more and enable it to resonate.

For me, composing comes just as naturally as speaking with words. I pursue sound with the desire of finding new things that can be done with it. When composing in a field of traditional music like hauta, the forms are set to some degree and those phrases can be used, and in the lyrics you can use word play to an extent.

In pieces that will be classified as contemporary music, as well, I want to be able to compose things that only the shamisen can perform, things that have the “language” of the shamisen and achieve a “fragrance” [flavor] of the shamisen.

The shamisen is by nature a monophonic instrument, but because it has “sound character” you can achieve expression purely with that, and that immediate opens up a new world of dimension [of musical expression]. When using an equally-tempered scale, you need to use more than one sound in order to achieve that kind of expansive effect, but with the shamisen you can do it with one [monotonic] sound. I feel that is what is amazing about the shamisen.- Back in 1977 you did the soundtrack for director Masahiro Shinoda’s movie Hanare goze Orin when you were 32. The year before that you had performed with the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra for the Tokyo Ballet Company’s production of Niji no hashi , and you went on to work on the music for film and television. Clearly you have worked on a wide range of projects.

- Since I had been active in a number of different shamisen genres, I was probably the easiest one for film or TV people to come to. And I myself was young and anxious to try a lot of different things. I even took on projects based in times when there was no shamisen music. Since there was of course some kind of music in Japan before the shamisen was imported, I tried to imagine what kind of music would be appropriate and then compose works within that concept. One of the things that has made me glad I studied minyo folk music, is that there are cases where some melodies of very old Japanese music remain in parts of old songs from different regions of the country. Sometimes I piece those fragments together to compose a song, like piecing together fragments of an old pot found at an excavation site to recreate the original.

- And you are able to do that because of the variety of different types of music you have studied since you became an independent musician, aren’t you?

- That’s right. Something my mother used to say often is to not just look at things without focus or purpose but to look well and then file what you have seen away in your drawers. I was also told to look at everything, both good things and bad. And since I have that approach in mind when I read a book, for instance, I will often hear something later and be able to recall that the same thing was written in such-and-such a book I read. So, when I am asked to write music to fit a certain era, its ideas come to me very naturally out of those draws of things I’ve experienced until now. I remember things that would be suitable and am able to use them. Things come to me intuitively that way. I once heard you sing a minyo from Ogasawara and was very surprised by it. Partly because it was the first time I had heard the music of the Pacific island chain of Ogasawara and also because it sounded like Micronesian folk songs. It gave me a renewed sense of how diverse the Japanese islands are. Was that a result of field work you have done?

- I have never been to the islands of Ogasawara, but I have listened to people from there sing their songs. Usually when people go collecting regional minyo, they probably get an introduction to a local singer and go to listen to them sing, but I don’t like to do that. My minyo gathering method is more like watching and listening to them sing from a more detached position. And as I do, I tend to absorb it all at once, like sucking the nectar from a flower. So when a sign a minyo from Ogasawara, it is probably different from the way other people sing it.

- Does that mean that when you re-produce the things you have gathered, the nectar, it comes out in a different form through your own personal filter?

- That’s right. When I learn an Ogasawara song and sing it, I am not an Ogasawaran, so I can’t sing it as they do. But I can recreate in my performance the image that I have gotten from their singing. Since it is not my job to copy them, I let the things I hear run through my own filter and then make it my own. So, in a sense, when I gather new songs I am re-arranging and composing at the same time. In the case of minyo, the same song will be sung slightly differently by any two people, and depending on the physical condition of the person at that moment, the tempo may become faster or the key may be higher and the image of the song may change completely as a result. You need to be able to see through those elements, to have the ears to hear those differences.

- So, are you listening to the songs as a resource for future use?

- Exactly. When I am singing, I vary the tempo of the songs depending on the songs that come before and after it in the program. Taking something like the Itsuki Lullaby, depending on its place in the order of that day’s concert, I might think, “It would be perfect to sing it with the beat and melody that so-and-so used.” In this way, for a given song I don’t learn just one way of singing it but several different rhythms and styles of singing it. That enables me to perform with much greater freedom.

- Since the 1970s you have been introducing Japanese shamisen music overseas on programs supported by the Japan Foundation and others.

- When I was younger, I had the opportunity to travel to a number of countries, like the U.S., Brazil and countries of the Middle East, and to experience there a variety of folk/ethnic instruments. That experience has been a great asset to me. I also had the opportunity to play with performers of traditional instruments in each country, which prompted me to re-consider Japan’s minyo music.

The world of the classics is something that developed as a performing art, I believe, but I think ethnic music is something that occurs spontaneously, and within that music is the spirit of gratitude for the blessings of the natural world. The classics are the spangled, man-made creations, while ethnic music has a different type of brilliance. I believe that we have to value our Japanese folk music and ethnic music much more than we do now.

One other thing I realized by traveling abroad is that, although Japan is a small country, it has many distinct and different regional characteristics and cultures, and even the sense of rhythm and pitch are different. The way people clap a beat is completely different in many regions. Realizing and polishing these regionally distinct traditions would surely be a great way to create wonderful folk arts groups and music or dance companies. And that makes me wonder why it isn’t being done.- For a three-week run beginning at the end of January, you will be serving as musical composer and performing live on stage in a London production of Shun-kin (a story about a folk song master and her apprentice). This production is based on the short stories Shun-kin-sho ( A Portrait of Shunkin ) (*5) and Inei-raisan ( In Praise of Shadows ) by the famous Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki (*6) and is co-produced by Tokyo’s Setagaya Public Theatre and Britain’s Theatro Complicite. Its world premiere was in Tokyo last year. It is directed by Complicite’s Simon McBurney and the cast is Japanese. How was it that you became involved in this production?

- The person who had been asked by Simon (McBurney) back in 1993 to find the shamisen performer who had the most beautiful sound in Japan, saw the 1993 production of Hamlet that I composed and played the music for and apparently liked it. That was a production of Hamlet staged at the Panasonic Globe Theater (now called the Tokyo Globe) and the Swedish director, Peter Stormare, said that since the play was being done in Japan he wanted to have the music performed on Japanese instruments. Eventually it was decided that the shamisen would be used.

When I met Simon, he said he wanted to do Shun-kin, which perplexed me a bit because the world portrayed in that story is jiuta (regional folk music: *7 ), which has a different sound from the shamisen I play. For people who know traditional music, they would be asking, “Why this kind of shamisen?” I then asked Simon if he still wanted to use me, knowing that contradiction. When he heard my shamisen, he said he wanted to use me in any case. When he said that, I decided to take the job. Then I began participating in the workshops for the production.- What kind of music did you decide to create for Shun-kin ?

- This play was ten years in the making. It is based on the works Inei-raisan and Shun-kin-sho , but at first it was mainly based on Inei-raisan rather than Shun-kin-sho . It is Inei-raisan ( In Praise of Shadows ) that depicts more directly the beauty of light and dark and the use of shadows in Japanese daily life, and in that case I thought I could do music with the right kind of expressive nuance.

As with the play itself, I began working on the music ten years ago. Simon divided the actors into groups and had them working on the script and staging [movement] for different parts of the story in a workshop method. Using this method he had each group do several scenes for a certain part of the story. When I first saw those workshops in progress, I felt that the work process was the same as composing and I thought that it was something I would be able to do. As the actors worked up a scene, I could work along and immediately come up with music through improvisation to go along with it. Each group had a different mode of expression, so the music came out differently in each case. Unlike musicians, the actors get into the scenes intellectually from a variety of perspectives and levels, and it was fun to be stimulated by that to compose music to go with it, thinking how to play each part and coming up ideas one after another. It was very interesting working with those actors.

Around that time, Simon asked me if I could act. I told him absolutely not. But in the end he had me on the stage performing the whole time. Although there was no actual acting involved, it was the same for me as if I were acting out a part as an actor. Just on a whim, I happened to give Simon a short explanation about the construction of the shamisen and showed him how the neck is separated from the body and then how the neck comes apart into several pieces. I took it apart and then reassembled it again. That is something I should not have done (laughs). Seeing that, Simon apparently had a moment of inspiration, because he added an opening scene just after the curtain rises, where I come out carrying the shamisen in a case and proceed to assemble it. Then, at the end of the play where the main character dies, the shamisen is left on the stage when the final exit is made and the curtain falls. Looking back, I realize that it is something that causes wear on the shamisen and I should have just kept my mouth shut instead of making that original explanation that led to those two scenes (laughs). I regret it a bit.

Assembling the shamisen there on the stage and then performing on it is in fact a very difficult thing. The shamisen is a sensitive instrument that is easily affected by changes in humidity and has to be tuned constantly. For this play, the instrument has to be assembled and the strings changed properly without damaging them before the play begins. Then the instrument has to be taken apart again and put in the case to be ready for the opening scene. Once the play starts and it is assembled again, I have to play while caring for the strings as best I can on it. Listening to your performances in hauta and other types of music, I would imagine that you like the type of aesthetic world Tanizaki creates in Inei-raisan ( In Praise of Shadows ).- Rather than calling it a world I like it, I would say there is a certain resonance that I feel in common with it.

For Shun-kin I have composed the music solely based on the movement of the play and a feeling for the inner beauty of the Japanese mentality, while trying to keep the sound as simple as possible. I believe that people in Western style music use chords to create music but, as I mentioned earlier, the shamisen is an instrument that can create images with just monophonic notes. When I’m performing in hauta concerts as well as other cases, I want to create the kind of music where the listener can be drawn in naturally, and once they are, I don’t need to make any displays of technique. I only need to give them the notes one by one as they flow from the strings, and allow the listeners to use those notes to weave their own world of music. So, I don’t play dramatically or with flourishes most of the time, just mostly in a straightforward, unadorned way. The shamisen is an instrument with the potential to create images in that way. And I will be happy if the audience at this play can feel the beauty of the sound of the shamisen.- It sounds like you began by getting Simon to understand the shamisen as an instrument, but did he have any specific requests regarding the music you composed?

- There were instances where he said things like that he wanted a stronger sound, but basically the music I was doing was in line with what he wanted, so there were no requests that he made in that sense. At times when he seemed to be thinking and not satisfied with what he was hearing, I would happen to be there and get an image of what he probably wanted, and when I changed to that sound, his expression would change and I’d see that he was now satisfied. And there were also contrary cases where listening to the music seemed to give him or others images on how the play should move.

That finally gave birth to the classic piece Awayuki , an original piece of mine, Koi no Tamoto from Kanginshu (a collection of popular songs compiled in 1518) and Yugao in the Tale of Genji . When the main character dies at the end of the play to that song plays, it is one of the themes of Shun-kin , I believe. It is all right with me if the Japanese audience hears it as a regional folk song or if it is heard simply as straightforward shamisen and simply ordinary music.- You have performed on the shamisen in collaborations with the musician Haruomi Hosono and with electronic instruments like the synthesizer, as well as with musicians performing on Western instruments. When you play with musicians using instruments that don’t employ the “ambiguity” [tonal variance] of the shamisen, how do you deal with that difference?

- Actually, I don’t look at the synthesizer as a Western instrument, I consider it similar to the geza music (offstage background musical accompaniment ensemble) in Kabuki. When I’m playing on the yamadai (onstage podium for the main musician) in Kabuki for example, the music coming from the geza is the same as that from a synthesizer. With that attitude, there is nothing awkward for me about playing with a synthesizer, rather it is quite familiar and I can ask for the kind of sound I want them to play. I get them to play lots of sounds and I search for the sounds I should play.

That was the case when I created the group ATAVUS, because I believe that music is fundamentally playing with sound. If you are true musicians, you can always play together, no matter how different your instruments may be. If you put a group of musicians of true weight and they come together on stage, they should surely be able to produce great music. I just want to share that experience and joy with people who love the stage. Because music has the kind of effect that can make you come to love another musician for the quality of the sound they can make, even if you don’t like them personally at first. Also, when you are performing in a collaboration, you have a tendency to let the other musician do their thing. It is fun to listen to the other person when they are making interesting music, and that can stimulate me to come up with interesting sound in response. What attracted me about working with Simon was that kind of feeling of stimulating each other to produce something new.- What was the biggest new discovery for you that came out of working with Simon?

- I don’t know if you would really call it a discovery, but it was very stimulating to see the perspectives that he looked at things from, and the things he was sensitive about. For example, there was the device of having the actor holding a single bamboo pole to symbolize the shamisen. That is somehow similar to the kind of Shamisen character I was talking about earlier. It is extremely simple, but from that single pole a whole world of expression can be imagined. It had a deep rhythm and at the same time it spoke to the viewer with the simple warmth of contemporary art. I am very grateful for my encounter with Simon.

- Since the main character in Shun-kin is a professional shamisen player, it must seem affected to you to see an actor who is not a professional pretending to play the shamisen in the play. It creates a poor image, doesn’t it?

- What the actor is holding is just a bamboo pole, but that device was effective for giving the audience the image of a musician playing. In theater, it seems that you have to leave that kind of room for the audience to use their imaginations to expand on what is actually seen on stage. The performers can’t do it all for the audience, there has to be a shared effort with the audience to create the world of the play. Shun-kin gave me a renewed appreciation of the unique enjoyment of performing live that comes from the fact that it only becomes complete when there is the audience that has come to actively listen and watch what is going on up on the stage. I now have a sense that working with Simon this time has brought me to a new turning point in my performing career.

- What do you especially want the people of London to appreciate in Shun-kin ?

- The simple, monotonal sound of the shamisen that is different from the harmonies created by other instruments. I will be happy if people are able to hear the quality of that sound. The facility we will be performing in will be different, so I will adjust the sound to fit that environment. To do that, we have included rehearsal time that will make my stay in London more than a month.

- The complex overtone known as sawari (touch [on the strings]) that is produced when performing on the shamisen is one of the instrument’s unique qualities, but to people used to hearing Western classical music it can sound like nothing but extraneous noise. I would appear that this is the reason that the shamisen has not come to be appreciated overseas as readily as other traditional Japanese instruments like the koto, shakuhachi and wadaiko drums.

- Sounds like the sawari of the shamisen are found in all types of ethnic instruments in all countries. They are instruments that people have made purely of natural materials, so each instrument has its own “life.” The instruments of [Western] classical music are instruments designed to create pure, distinct sounds when played in ensemble with other instruments. Therefore, their expressive qualities and purpose are different from ethnic instruments. I hope people will see that the shamisen is an instrument that can produce the kind of finely nuanced sound that touch innate human sensitivities.

Also, I will be singing in Shun-kin, so I want the audience to get some appreciation of the appeal of [traditional] Japanese use of the voice. I believe that the human voice is the most wonderful instrument of all and even in very short songs like hauta , just a couple of lines of a song can bring the listener to tears. Short songs, including folk songs, are moving because they sing directly about true emotions. Since the human voice is the only instrument that can deliver both emotionally moving words and meaningful music, I hope very much that the audience will appreciate the Japanese voice in these performances. - In my case, it was a situation where I was forced to go independent. At the time, our shamisen world had no family-line [school] system, so I thought that as long as I had to go independent, I would start my own family-line school of shamisen music under the Honjoh name. It was partly the impertinence of youth and I regret it now, but I thought that if I created my own family-centered school, apprentices would come and support my musical activities and make it possible for me to pursue the kind of shamisen music I wanted more freely (laughs). So, I started a new genre of music that I called Risougaku and gave myself the new name Honjoh Hidetaro so I would be the founder and head of a new family-centered school. I regret that now.

Hidetaro Honjoh

The world of Hidetaro Honjoh – pursuing shamisen music as a traditional Japanese folk art, and even venturing into British contemporary theater

Hidetaro Honjoh

Born in 1945, Honjoh is one of Japan’s representative shamisen performers and composers. He studied nagauta under Yoshie Kineya and minyo under Fujimoto Hideo I. In 1971 he went independent and established the Honjoh school [style] of shamisen, adopting the professional name Hidetaro Honjoh. He continues to teach performers of the next generation as the family head of the Honjoh school of shamisen while engaging in a wide variety of activities, from performing the traditional classics to composing and performing for movies, stage and television. He is constantly undertaking new activities, such as his establishment of the group ATAVUS, aimed at reviving and re-establishing hauta and Japanese ethnic music. He has won a large and appreciative audience with the tonal beauty of his shamisen and the richness of his singing voice.

Interviewer: Kazumi Narabe

*1 Shamisen

The shamisen is a Japanese plucked string instrument. It is constructed of a body [sound box], consisting of a rectangular wooden-frame box with skin stretched on both sides, and a long neck that passes through the body. The tree strings strung on the neck are plucked with a plectrum and/or the fingers. The origin is said to be the Chinese three-stringed sanxian , and according to the accepted theory it came to Japan in the 16th century via the Ryukyu islands (present Okinawa islands). As a newly imported foreign instrument, the shamisen soon became popular among the common people and its use spread quickly to everything from minyo folk singing and theater music for Kabuki and the like to more artistically sophisticated chamber music like jiuta . Thus it eventually became a central instrument in Japanese music. As the instrument was improved and new methods of playing it were developed, numerous and varied genres of shamisen music were born. In the process, these developments gave birth to unique Japanese music forms such as the katarimono (narrative shamisen), typified by the shamisen of Bunraku puppet theater that accompanies the narration of the tayu narrator, and utamono (song shamisen) that accompanies the singing in nagauta and the like.

*2 Nagauta (shamisen)

The shamisen that Honjoh usually uses is a mid-sized shamisen, among the various sizes of the instrument in use today. Nagauta is a genre of that developed as the accompaniment music for Kabuki theater in Edo, (present-day Tokyo). As a result, the nagauta shamisen is characterized buy its ability to produce beautiful high notes and its rich tonality of sound.

*3 hauta

This is a form of popular song born in the middle of 19th century. It was a very popular form in the country’s political capital, Edo (present Tokyo). It consisted of short, stylish or witty verses sung to a shamisen accompaniment. Since 1993, Hidetaro Honjoh has been presented a series of concerts of classical and new hauta titled “Hauta – Listening to Edo.”

*4 Risougaku

A form established and named by Hidetaro Honjoh that attempts to revive and recreate the minyo [folk] songs he specializes in. Honjoh adds contemporary interpretations to existing minyo to make them more relevant and alive to contemporary taste.

*5 Shun-kin-sho ( A Portrait of Shunkin )

This is the story written by Junichiro Tanizaki of the life of shamisen mistress Shunkin, the beautiful second daughter of a wealthy Osaka merchant family, portrayed through the eyes of her faithfully servant, Sasuke. This is one of Tanizaki’s representative works that combine traditional aesthetics with his particular obsessions.

Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965)

One of Japan’s representative authors, Tanizaki is known for a literary style, called akumashugi (demon-ism), defined by sensuality and often taking the femme-fatale as its subject. Words such as aestheticism, eroticism, fanaticism, romanticism and masochism are often used to describe his works. Born in Tokyo, he eventually moved to the Kansai region (Osaka, Kobe, Kyoto) and his youthful interest in things Western shifted to an interest Japanese tradition and aesthetics that is reflected in the many works he wrote during his career. Among his representative works are Sasameyuki ( The Marioka Sisters ) about the daily lives of four beautiful sisters, Chijin no ai ( Naomi ) and Tade kuu mushi ( Some Prefer Nettles ). Tanizaki also worked on a modern colloquial version of The Tale of Genji .

*7 Jiuta (shamisen)

Jiuta shamisen is one used in the jiuta music that developed in Osaka and Kyoto, known as kamigata music. Jiuta is traditionally a music/song form passed down through generations of blind performers. In the feudal period, music offered a means for the visually impaired to support themselves and live independent lives. In the story Shun-kin-sho , the main character, Shunkin, is a blind woman who lost her eyesight as the result of illness at the age of nine. By devoting herself to the study of jiuta, she eventually becomes a master musician. The size of the shamisen instrument determines the thickness of the strings and the plectrum. The playing technique and, naturally, the sound also vary with instrument size. Jiuta shamisen is larger than the nagauta shamisen with a slightly thicker neck. The most distinguishing characteristic of the jiuta shamisen is the presence of a metal weight made of lead or other metals in the bridge on the instrument’s soundboard that holds the strings. Varying the size (weight) of this bridge weight enables slight adjustments in the sound of the instrument. The jiuta shamisen is usually performed in ensemble with koto or shamisen and is basically a chamber [music] instrument for use in the home or [tatami] parlor/banquet rooms.

Photo: Daisuke Ishizaka

Photo: Daisuke Ishizaka

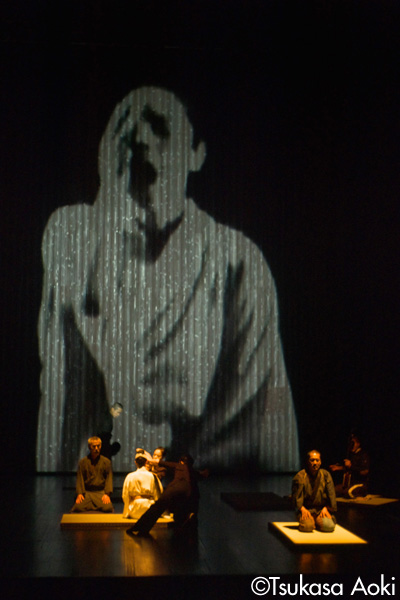

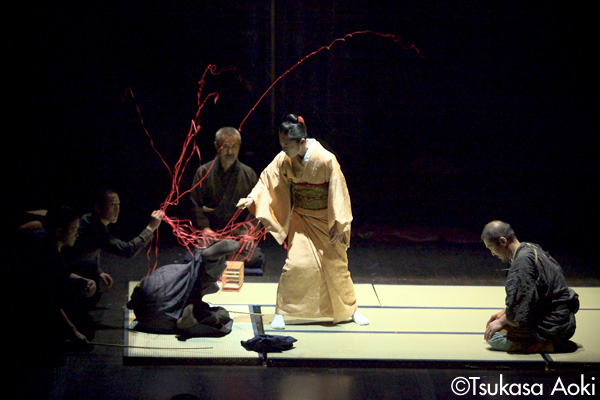

Shun-kin(Co-produced by Setagaya Public Theatre, Complicite)

(Feb – Mar 2008 at Setagaya Public Theatre)

Directed by Simon McBurney

Performed by Eri Fukatsu, Songha Cho, Hidetaro Honjoh and more

Photo: Tsukasa Aoki

Shun-kin

Photo: Tsukasa Aoki

Related Tags