- Could we begin by asking what originally got you involved in puppet theater?

- I was born in 1961 and as a child I loved watching the children’s shows on TV that used puppets, like “Hyokkori Hyotanjima” and “Thunderbird,” and also the “Ultraman” series using rubber-suit superheroes. There was great vitality in the television industry in those early years and I think its influence was especially great. My mother was a kimono seamstress and there was always a lot of kimono material in our house. From about the age of three I was making puppets with my mother using scraps of material and wood spools, or stick puppets that imitated the Hyokkori Hyotanjima characters. In nursery school I said I wanted to do a puppet play and did a puppet version of the story The Gigantic Turnip based on the Russian folktale about a family who work together to pull a giant turnip out of the ground. In elementary school I got my friends together to do a puppet play for our culture festival.

- Did you make your own puppets back then?

- Yes I did. I made them with my friends. I guess I was what you might call an otaku today. At the performances I was recognized as the leader, so I worked hard with everyone. But at other times I tended to stay home making puppets (laughs).

- Another puppet theater artist active today from the next generation younger than you, Jo Taira, is also from Sapporo, Hokkaido. He also says that he was doing puppetry when he was a child. Is there some special tradition of puppetry in Sapporo?

-

Sapporo has the first public puppetry theaters for children ever established in Japan. They are the Kogumaza (Little Bear Theater) established in 1973 and the Yamabikoza (Echo Theater) established in 1988. Kogumaza is exclusively for puppet theater and the Yamabikoza is a children’s theater where children’s plays and puppet theater are performed. Both theaters were established by the former mayor of Sapporo, Takeshi Itagaki. When Sapporo and Munich became sister cities he went to Europe and one of the things he saw in Munich was the national puppet theater. He thought it was a great thing for the children in a society recovering from the devastation of World War II. That is what prompted him to establish the Kogumaza.

The administrative director of the Kogumaza was a Sapporo city official by the name of Hiroshi Kato who happened to be a close friend of the director of the Puppet Theater Company PUK, Yasushi Kawajiri. Both of these men have passed away now, but they were of the generation that started puppet theater in Japan from virtually from scratch in the poor years just after World War II. When my generation came up, the Kogumaza they started was mainly used by students and adult groups, but lately amateur housewife groups are very active. There are about 40 puppet theater companies in the area and these performances being given almost every week.

That is the kind of very widespread puppet theater culture Sapporo has, and it has given birth to very talented people like Jo [Taira] whom you just mentioned. I saw Jo perform at Kogumaza when he was just a sixth grader in elementary school and I remember thinking that he must be a genius. There have been other extremely talented young people as well, but the problem is that even if they continue puppetry through middle school and high school there is no system for people to become professional puppeteers in Japan. Many people give up their dream of becoming puppeteers when they realize this and turn to actor other professions, and that is a shame and a waste of talent. - What kind of puppet plays did you create as a young student?

-

When I was a student it was a time when the national TV station NHK was running broadcasts of one of Japan’s representative puppet-acted TV shows “

Shin Hakkenden

” produced by Jusaburo Tsujimura, and at the time puppet theater in Japan was mostly a medium for children’s stories, with nothing geared for college students. So, I wanted to make puppet plays that college students would want to see, thinks that I would want to see. What I wrote were puppet plays influenced by the plays of playwrights of Japan’s small-theater movement I liked, such as Juro Kara, Minoru Betsuyaku and Yoshiyuki Fukuda. I particularly liked Fukuda’s

Sanada Fuunroku

and I must have read it 100 times as I was writing my puppet plays.

I also wrote a silent theater version of Macbeth . I got about 20 friends together so three were lots of puppets in it, and it also included a student band playing live with three synthesizers, three electric guitars, drums and folk instruments. It was on a scale that I could never work on today, but at the time everyone pitched in and helped me out. I was in the Education department of university at the time and there were still some remnants of student activism. Even though I had joined the puppetry club, but it was an era when everyone was more interested in going to the student demonstrations than making puppet plays. Ours was the last generation involved in student demonstrations like that. - After graduating from Sapporo University, you entered the Hitomiza company in Tokyo in 1985. How did that come about?

- It happened because Shiro Ito of the Hitomiza had seen one of my plays at a Sapporo festival or someplace and he invited me to come. I think it was a play where I directed an amateur adult theater group. It was around the end of the student activist movement when students and working adults were full of energy and there were puppet theater groups in all the universities and junior colleges in Hokkaido. The students and working adults in the puppet groups would get together once a year to do a play. I think it was one of those plays that Ito saw.

- I believe that at the time Hitomiza was mainly giving performances for young children at elementary and nursery schools. Was it a different environment from what you had imagined and what you wanted to be doing?

-

It naturally was different from what I wanted to be doing but I believed that I shouldn’t let myself be disappointed by that fact. At first I was assigned to the nursery school brigade and I would have to get up at a little after 5:00 in the morning and go around to the nursery schools of Yokohama, Kawasaki and Tokyo giving puppet performances. After those rounds I would return to Hitomiza and work at making puppets and stage art for the school performances, then at night some of the senior members would say, “Sawa, now were going to make a puppet play for adult audiences.” So I would work on that too and then when we were finished we would go out drinking. After burning the candle at both ends like that for about a year I got a high fever that put me in the hospital.

I should interject here that when I was in college I spent some time traveling around Europe and I met a priest in Paris and ended up being baptized a Christian by him. Then later when I was at Hitomiza and feeling lost about where I was headed, at the suggestion of one of the people in the company I started going to a church in Tokyo. And, while I was lying in bed in the hospital after collapsing the minister from that church appeared in one of my dreams.

In that dream the minister was leading me down a corridor with white nameplates sticking out from the wall at each door. Then he turned to me and said, “Look behind you. Who do you see?” “What?” I said, and turned around to look. What I saw was a black hole that I somehow knew intuitively to be my illness. “I can’t left myself be sucked into that hole,” I told myself. When I woke up from that dream my fever had gone down. After that I went back to Sapporo to rest and recuperate for about a month, and it just happened to be a time when they were interviewing for someone to fill an opening for an art teacher at the Hokusei Gakuen girls middle school. I thought it must be fate, so I applied for the job and got it. And when I went to the school, the corridor in front of the art room looked just like the corridor in that dream. Before that I was a rather nonchalant Christian, but since then I have become more serious (laughs). - Why did you quit your job as an art teacher and go to Europe to begin puppet theater again. ?

- Mr. Kato of the Kogumaza told me that he had heard there was a graduate school for puppet theater studies at Charleville Mezieres in France and why didn’t I go study there. I couldn’t speak French and besides I was responsible for a senior class at the high school I was working at, so I thought it would be impossible. But a lot of people were behind cheering me on with support and when I applied for a public grant thinking that I didn’t have a chance, it was accepted! After that I felt that I had to go. And as I was debating in my mind what to do, one of my fellow teachers told be, “When a child is born there are more than a thousand career choices open to it. But when that child enters a Japanese elementary school that number suddenly drops to 500, and when the child enters middle school the number drops again to two- or three-hundred. When the child enters high school, only about 100 choices are left, and if the child goes on to college there are then only a few dozen career choices that college will prepare the child for. In that way, the education we are conducting here in Japan gradually narrows the paths open to a child. But even an old man who has been told that he might die tomorrow may still have some hidden talent that may blossom. So you should definitely go [to France],” he said. That helped me make up my mind.

- That was in 1991, wasn’t it?

- Yes. I went to participate in a 5-week summer workshop called Babel Tower at the Charleville Mezieres graduate school. I was then supposed to enter the graduate school for the autumn semester, but there was a misunderstanding that prevented it. And, as I was at ends and not knowing what to do next, the instructor of the summer workshop, Josef Krofta invited me to come to the Czech Republic. I went there in 1992.

- What did you actually do in the Babel Tower workshop?

-

As you know, the Tower of Babel is a story from the Old Testament about a huge tower that the people were building to try to get up to God’s height in the heavens. This angered God and he made the people, who all spoke the same language at the time, suddenly all speak different languages. Babel Tower is a theatrical workshop based on the idea of how people of different languages find ways to communicate in a confused post-nuclear holocaust world. I believe there were 27 people from 15 different countries in the workshop and we were all told to speak only in our native language, which meant we were speaking in 15 different languages.

The play begins with a scene where a tower of about 200 cardboard boxes has collapsed and we are all crawling out from under that rubble. The actual work of putting together the play was done in English, but even the English that we from the 15 countries spoke wasn’t good enough for real communication, and I myself am very bad at English.

On the second day of the workshop we are all unable to communicate, but we decide to at least decide when lunchtime will be. One French person said the restaurant he liked was only open from 2:00 to 4:00 so let’s make that the lunchtime. Then the Germans said, we are here to work, so we don’t need a lunch any longer than from 12:00 to 12:45. The British said that they wanted a tea time at 3:00, and the Italian said, “I’m fine with any time as long as I get enough to eat and can have some time for a nap after eating.” That made Krofta mad. He said “Everybody shut up!” and the lunch hour was set from 12:00 to 1:00.

It is such a typical story that you can’t help but laugh. When someone asked me, “Nori, what time do you want lunch to be?” I said, Any time is OK with me.” Then I was told, “You Japanese!” (Laughs) That was how those five weeks went. - Didn’t you make any puppets there?

-

I went to a scrap heap and found some rubbish to make puppets with, but Krofta’s basic rule was only to bring in a puppet when one was absolutely necessary. That was a firm rule. If you can’t answer the question, “Why is a puppet necessary here?” then it is best for you to just walk through the scene yourself as a person. That concept was completely different from any puppet theater I had known until then.

For example there is a scene where a baby comes floating down a river in a cardboard box and we come out dressed in rags and rescue the baby in the box. But there is no puppet of a baby in the box actually, there is just the sound of a rattle to express the presence of the baby and we all act as if there is a real baby in the box. Then at the end we show the audience that the box is actually empty.

In Krofta’s mind, we can manipulate a box to make it look like there is a baby inside because we are puppet theater puppeteers, but it is nothing more than an empty box. He said that through this work he wanted to show us that a baby is a symbol of the future and hope, but that hope should be inside of us, the puppeteers. The work that came out of that Babel Tower workshop was actually performed as a finished work the following year by his DRAK puppet theater company. And of the original 27 people who participated in the original summer workshop I was the only one to perform in the DRAK production. We also toured with that production and there was a long run in Prague of about two months. - Was something like that Babel Tower workshop revolutionary at the time in Europe?

- I believe Krofta was doing that kind of workshop in various places around Europe at the time. But the one I attended had people from 15 countries, so it certainly must have been one of the largest he did.

- Czech puppet theater is world renowned and the DRAK company is especially famous. Can you tell us about DRAK in some more detail?

-

All the larger cities in the Czech Republic have public puppet theater companies, and DRAK (which means dragon in Czech) is the public company of the city of Hradec Kralove with a history of about 50 years.

During the 1960s a woman producer Jana Drazdakova brought Krofta, the artist Petr Matasek and the musician Jiri Vysohlid to DRAK. These three geniuses worked together on her productions from the 60s through the 90s and there presence brought great changes to Czech puppet theater.

At the same time there was a major rebirth in puppet theater in Poland. It was a time when the socialist system was breaking down and there was a sense of urgency that if they didn’t do something to tie in with the audience, the theaters would go under. That is when they started creating plays where live actors began performing on the same stage with the puppets. Up through the 1990s DRAK was the front-runner in that renovation of puppet theater. Now those three artists are all in their mid-60s and Matasek already quit DRAK seven or eight years ago. With the change of generation taking place now things are undoubtedly changing, but for those 30 years I feel it is safe to say that DRAK was a world leader.

DRAK has created a variety of different works involving an interaction of puppets and people. For example, in a collaborative project with Israel they created a work in which people in a closed train bound for a Jewish concentration camp turn into puppets during the course of the journey. There was also a work that was an omnibus of Beatles numbers, which had been banned during the communist era. While singing the words of the Beatles song Nowhere Man about man who can’t see the truth; “he’s as blind as he can be” “just sees what he wants to see” “isn’t he a bit like you and me”—I think that’s what the lines were. And as they sing they are taking apart an anatomical model of the human body. At the “he is blind” part they take the eyes out, at the “he doesn’t speak” part they take out the throat and the innards and throw them into a bucket along with the bones. When there is little left of the anatomy model but bones, they begin manipulating it as a puppet. It is at once very comical and grotesque at the same time. With Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da a boy and a girl playing with each other using puppets made of crumpled up pieces of paper with test notes on them, and in the end they burn them. - Did you become an actual member of the DRAK company?

- I did many collaborations with DRAK but I never actually joined the company. In 1992 I began studying drama and puppet theater as a student of the Czech national Academy of Performing Arts in Prague where Krofta taught. The department had a very long name including “alternative” and “figurative” and “artistic expression relating to puppets,” and it was a name that Krofta had created. For a while the word “alternative” was the buzzword in Europe and it expressed the idea that if there was one main path there would always be an alternative path and either of them could be walked with freedom. I entered the design department of a school that aimed to raise actors who could also use puppets, singers who could also dance, mask actors who could also do acrobatics. And my instructor of that faculty was Matasek.

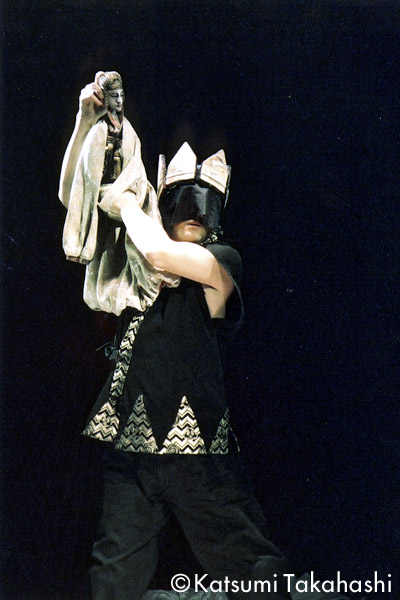

- One of your representative works is Macbeth and, if I remember correctly, it premiered in 1992. It is a solo play where you act the part of Macbeth wearing a mask while you manipulate a puppet in the role of Lady Macbeth.

- My Macbeth is a work that I created with Matasek while I was training at the Academy in Prague. We decided to work on a play that we both knew, and it turned out to be Macbeth. I believed I had no talent as an actor and I didn’t want to do a solo play by myself, but I was told that it would sell (laughs). It is a silent drama and also a colorless one with the set, the puppet and my costume all in white, black or silver.

- Did you design the puppet and the stage art?

-

That’s correct. Vysohlid said I should make a device of scrap iron that would produce sound, so I made a set with a ladder in the middle and branches extending out form which I hung a crown made of sheet metal and scrap and masks and puppets in away that I could make sounds at I physically manipulated or dumped into the different parts in the course of the play. When I performed the piece in Japan, however, I made it a colorful set instead of a monochrome one.

During one performance of Macbeth I lose about one kilo in weight. At first I didn’t know about proper breathing technique and I thought I was going to die along with Macbeth out there in the course of the performance (laughs). There were several times when I wanted to just quit in the middle of the performance. - Why did you make it a silent drama?

-

With all my plays, not just

Macbeth

, I make it a point to avoid bringing in words with meaning. The main reason for this is to ensure that it is a piece that I can perform anywhere. There are some exceptions, like

Romeo and Juliet

( A PLAGUE O’BOTH YOUR HOUSES!!!), but since I have clients in many countries, I am in trouble if I don’t have a repertoire that can be performed anywhere regardless of the local language.

But now I want to create plays that use words. But when I say words with meaning I mean words in the sense of the yatta! (I did it!) in HEROES where you know what the character is saying even if you don’t know the language in which it is spoken. It is a difficult task, however. - What made you think to make Lady Macbeth a puppet?

-

Since the Czech theater principle is that everything that appears on the stage must have meaning, you could never see anything like the

kuroko

(black costumed hooded stage hands) of Japanese traditional Bunraku and Kabuki theater whose very costume says, “Pretend I don’t exist.”

If you are going to appear on stage it must be in a capacity that gives vital information to the audience. So, I experimented with a number of possibilities and finally concluded that, no matter how hard I might try to act out the part of Lady Macbeth with my own body, it is still going to look like a man (laughs). So I decided Lady Macbeth would be a puppet.

In the play I make my entrance as a dark, unseemly figure with the look of a poor itinerant street performer, and I begin to pick up things resembling bones lying by the roadside and piece them together into a mask. When I put on the mask I become Macbeth, and at the end of the play I remove the mask and return to original dark figure before leaving the stage. Matasek said to me, “Aren’t there men who think they are dominating their wives but in fact the wives are manipulating them?” That made me realize and adopt a relationship in which the puppeteer is actually being controlled by the puppet. - This concept is different from the “ dezukai ” (the main puppeteer appearing on stage without a head/face covering) of Bunraku, isn’t it?

- Yes. But it isn’t as if they don’t know about dezukai and the concept. During the socialist era when the puppet theater company people were all civil servants with their income guaranteed by the government 100%, they were able to try all kinds of methods. That is when they brought the puppeteer out from behind the wall that had always kept them out of sight and came to the conclusion that the puppeteer has to be able to perform as an actor as well.

- Do you write a text for your silent dramas?

-

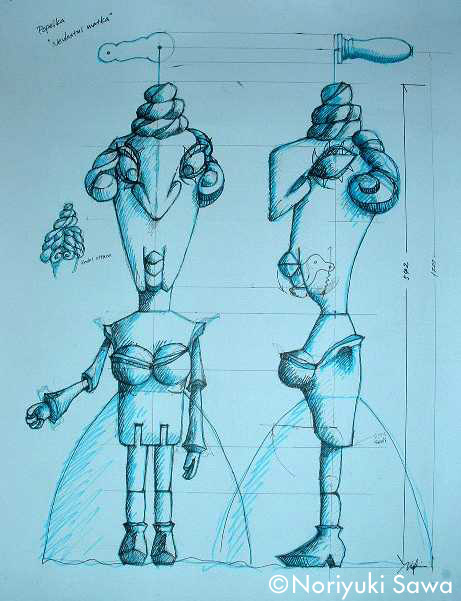

I write a text and I draw pictures. Countless times I have written a script full of stage notes only to have Matasek cross them all out and have me write the text over again. During the course of rehearsals the contents also change, so rather than writing a scenario as such I will draw pictures to check the balance of the symbolic elements of the things that appear on stage. For example, in the case of Lady Macbeth the symbolic elements include the fact that she is a woman, she is small, she is a puppet being manipulated but she is actually controlling her man. I draw pictures to make sure these elements are being communicated visually.

In addition to these drawings, I make life-sized design drawings of the puppets. When I make the puppets myself I know what I want, but when I have them made for me by the company’s workshop I do a full life-size, 1 to 1 scale blueprint of the puppet to make sure there is no misunderstanding. And in the latter case, when I have the workshop make the puppet, I will still do the final finishing myself. - You order puppets to be made by a workshop?

-

As I mentioned earlier, many of the puppet theater s in the Czech Republic are first sector public institutions. In the case of the puppet theater company in Ostrava called Divadlo Loutek Ostrava (The Municipal Puppet Theatre Ostrava) it has 20 actors/puppeteers, three people staff the puppet workshop, two or three people staff the large props workshop and two or three people are in charge of the costume department. I send my orders for puppets props and costumes to them in the form of design drawings or blueprints. At the theater there are performances every morning at 8:30 and 10:00, so the work in the workshops starts before that at about 6:00 in the morning. After the performances, the actors rehearse through the afternoon into the evening. Then the day ends with design work and scenario corrections and revisions at night.

On some days there are also two stages in the afternoon, so we are working at 100% capacity full time. At Ostrava we give 470 performances a year. The capacity of our theater is 250 people and with the school children coming to see a new puppet play every semester, they are coming by bus all the time and the theater is always full. Our puppet theater works are divided in ones for nursery school and lower elementary school age, ones for mid- to upper elementary school to middle school and high school and then a third type for adults, and we are making new plays every year. So the performers have to have an active repertoire of about ten plays that they are performing in rotation day by day.

The theater has a producer and an artistic director and there is also a dramaturge who is responsible for planning the marketing strategy concerning why the theater should be doing this particular work at this time and taste the staging should be done in. There is also a division of labor in the theater work, with staff in charge of taking care of the puppets after the performance and other staff in charge of hanging up the costumes. - Such facilities and a staffing certainly show what an important position puppet theater still has today in Czech society.

- As it’s written in the travel guidebook, during the Hapsburg rule of the 18th and 19th centuries, the only places where the use of Czech language was permitted in public performance was in the puppet theaters and by traveling performers. So, the Czech Republic has that history where puppet theater was helping to maintain the national identity. That’s why the national Academy for the Arts has a puppet theater department. It is a country with a special fondness for theater, and even its former president, Vaclav Havel, is a comic playwright. If you translate that into Japanese politics it would be as if Koki Mitani were Prime Minister (laughs).

- It truly is an interesting country (laughs).

- Havel became president thanks to the active support of the country’s cultural elite and theater people, but he ended up saying it was too stressful a job for him. On a national telecast he even said, he’d rather be in bed with a woman than be president (laughs). That’s the kind of country it is.

- What is the relationship between puppet theater and other forms of theater?

- It is a relationship where the boundaries are unclear. Now Matasek isn’t doing puppet theater but creating plays for the national theater. At the Ostrava puppet theater as well you don’t see puppets appearing much anymore, and they are now writing plays that don’t include puppets. And since all of the puppeteers can also act, the profession is becoming more and more borderless.

- How many plays are there in the repertoire of puppet theater plays you have created?

- Of my solo plays alone there are 25 to 30. They range in length from long works like Macbeth that are 40 minutes or so in length to short one of just one to three minutes. Of these five or six are long works. The number grows when you include the works that I have done the directing and stage art for. In terms of type, there is also a variety, such as ones using an overhead projector to create a shadow play affect. My latest work, Kaguya Hime doesn’t use an OHP but I consider it a video oriented work.

- It seems that you often use Japanese folktales and Shakespeare for your subjects?

- Not really. I use a variety of sources. For my longer works I make a point of using traditional stories, but I choose my sources more freely for shorter works. My subject may be a crab or a fish and there are times when I am struggling near a deadline and wondering if it really looks like a crab. Since I started out in design I may get my ideas visually first. For example, the visuals move and transform and the story develops out of these changes.

- I feel in your works like Macbeth that your use of color is very Japanese.

- I like beautiful colors. And although I haven’t been particularly conscious of it in the past, I find that my choices in colors and materials have unconsciously been Japanese in flavor.

- While continuing your activities in puppet theater in the Czech Republic have you found sensibilities that feel to be uniquely Japanese?

-

I have. It is hard to explain but the spaces, but I feel that the distances maintained between people and things are different in Europe and Japan. For example, when Czech people greet each other they hug and kiss, but there is no involvement between these people. Japanese only bow to each other, but I feel that there is greater involvement. I would summarize as a difference between solids and liquids. In Europe people say “It was fun” and hug and kiss each other, but there is an underlying acknowledgement that your fun is different from mine. Japanese mix like currents of water flowing together, but in Europe there is the definite division of individual and individual, stone and stone; they may work jointly, but there is no complete mixing.

That difference in the way people interact also reveals itself in the distance with things (puppets). In Europe a puppet never becomes more than a thing, but in Japan it is perceived as something mystical that can harbor a life of its own. I don’t necessarily have that sense, I think that kind of Japanese puppet theater will be highly regarded if it is performed overseas. - How is Japanese puppet theater actually viewed in Europe?

-

It is viewed as a wonderful art. The interest in traditional Japanese puppet theater is especially strong and there is much research is being done. When I did

Romeo and Juliet

with Krofta he said something interesting. “When I saw Japanese Bunraku I wondered if the three people behind the puppet couldn’t be put to better use? (laughs). I said, “But they are masters.” He answered, “I am a university professor. I can see that they are masters, but even though they are trying to make themselves “invisible” their visible presence there on stage is undeniable.” He went on to say that he wanted to give a name to the theatrical meaning of those three puppeteers and give them clear meaning. When I asked him if he wanted to make them characters in the play, he said, “Yes.”

That led him to make a play in which the three puppeteers behind Romeo became members of the Montague clan and the three behind Juliet became members of the Capulet clan. The family tries to manipulate their children (puppets) at will but the children (puppets) dislike being manipulated and eventually leave their handlers and end up as heaps in the floor committing suicide. It is a simple concept, isn’t it? That made me realize something important and convincing.

In his text describing Romeo and Juliet , Krofta used the expression “the empire of movement.” What he meant was that the three puppeteers behind the Bunraku puppet have status and a clear hierarchy, as if an empire were moving the puppets. He went on to say that he found boundless appeal in this tradition, like new land that has never been put to the plow. To them, I think Japanese traditional puppet theater represents a treasure chest of new themes and ideas. As with the Theatre du Soleil’s production Tambours sur la Digue , people really want to try things with it, but there are few cases where it has been done successfully. - What do you think is it about Japanese puppet theater that they feel attracted to?

- I think it is probably a keen sense of articulation. There is something very clean and unconfused about the theater Japanese create. I would describe it as a keen sharpness in English. What we call a pure and gallant “cleanness” ( isagiyosa ) in Japanese is something that they cannot express. I think it is the appeal of that cleanness that attracts them.

- What do you yourself think of the state of Japanese puppet theater? Speaking frankly.

-

Japan has produced a unique

manga

and

anime

culture, but in each country there is a unique culture that cannot be expressed in any other medium. For example, in the Czech Republic there are many small theaters and young people go there in the evening to watch puppet theater or plays and then stop by a pub to drink beer before they go home. In Spain everyone dances. In elementary schools there are “Theater” classes that are taught by instructors who might be the directors of small local theaters. They come to the schools and teach the children dance and drama. Unfortunately, Japan has not taught that kind of culture.

I may be dreaming but I think what Japan needs is an educational institution where people could study all the world’s new puppet theater methods. It wouldn’t have to have its own facility. It could just be done on an intensive summer seminar basis, where artists are trained and financially viable plays are created so that performers and designers could make a living from puppetry. Even if you raise good artists, it is meaningless if there is no market for them to make a living in, but that is something that takes a long time to create. So, we have to start from things that can be done now. - Are there any types of new puppet theater you want to create?

-

I have started an effort with

Kaguya Hime

and what I want to do is a kind of figure theater that is based primarily on [stage] art. Krofta’s method is very intense and powerful, and throughout Eastern and Central Europe, theater is generally under the firm control of powerful dramaturges, which over the past 30 years has created a situation where the puppeteer/actor has a more prominent position than the puppet. I think the puppets should be given a little more respect and freedom.

At the Academy in Prague we are beginning to see a bit of rebellion against the Krofta method, and we are seeing a new trend toward a more serious approach to the puppets themselves and their manipulation. This kind of change occurs in every generation. When Krofta was young, the mainstream was puppeteers who dedicated their lives to the handling of marionette puppets, and he was criticized as a villain who was destroying the important illusion of puppet theater. Now that everyone has experienced the Krofta method, the new generation seems to be returning to a love of puppets.

I am seeing this in the works of the students I teach at the Academy in Prague. For example, in a story like Warashibe Choja where a boy who manages to get a cow and then goes on to get one thing after another, the cow is made of tin and as the play progress people and things fitted with magnets become attached to the cow one after another. When the scene calls for a wall in the background, the puppeteer (actor) uses his/her own body to express the wall. If the scene calls for a slope, the puppeteer uses his/her arm to create the slope. Since they have been trained as actors as well, they do these things naturally and almost unconsciously. When the scene calls for water to be brought in, they puppeteer tucks the puppet under his/her arm and becomes an actor who then runs off to get water. Today’s new generation has been brought up to do these kinds of things naturally.

Noriyuki Sawa

A look into the world of performer Noriyuki Sawa With the new form of puppetry known as figure theatre

Noriyuki Sawa

Born in 1961 in Sapporo, Hokkaido. Noriyuki Sawa was part of the puppet theater Hitomiza and an art teacher before going to France in 1991 to study puppetry. In 1992 he enrolled at DAMU (Academy of Performing Arts) in Prague, Czech Republic, to study puppetry and now works as an instructor in the same school and as a puppet artist, director, and performer based in Prague and active mainly in Europe. In 2001 Sawa co-produced the international project MOR NA TY VASE RODY!!! A Plague O’Both Your Houses!!! – Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet with The Japan Foundation and the Czech puppet theater, Theatre DRAK. Among his representative works are his Macbeth solo silent drama using masks and puppets and King Lear using shadow play techniques. He has won the Franz Kafka Medal, the Prague Children’s Theater Festival Grand Prix, the prize for Best Performance for Children in the International Puppet Festival in Ostrava, Czech Republic.

Interviewer: Chiemi Tsukada

Noriyuki Sawa meets Hirotoshi Nakanishi “KOUSKY IV”

(March 2007 at Aoyama Round Theatre)

Photo: Shozo Kajiwara, STARKA

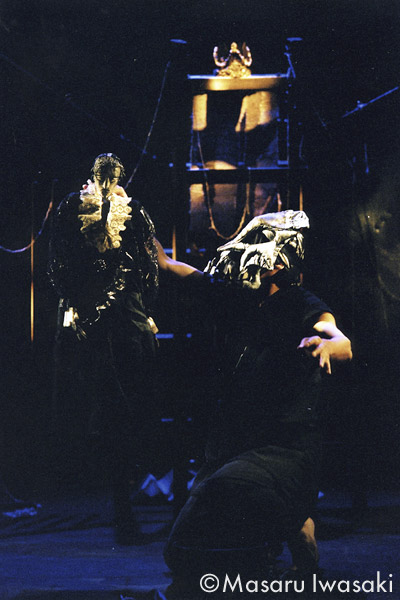

Macbeth

Photo: Masaru Iwasaki

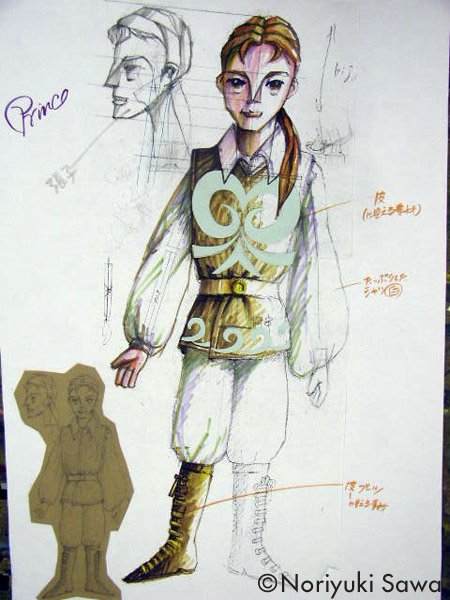

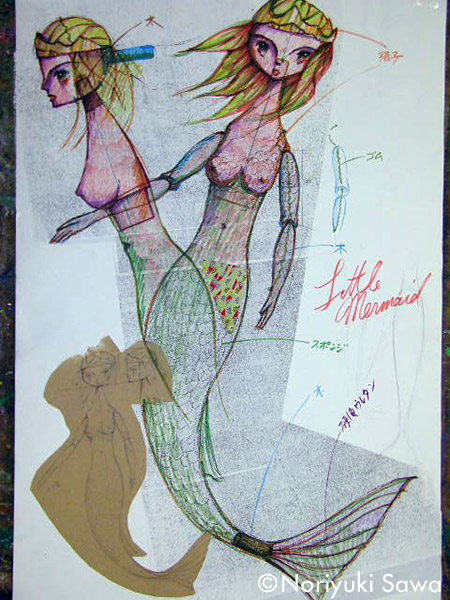

Japan-Czech Republic Joint Contemporary Puppetry Project

The Japan Foundation + DRAK present

MOR NA TY VASE RODY!!! A PLAGUE O’BOTH YOUR HOUSES!!!

Based on Romeo and Juliet by W. Shakespeare

(Toured in Hradec, Warsaw, Prague, Pécs, Tokyo, Iida, Sapporo; June-August, 2001)

Photo: Naoki Harada

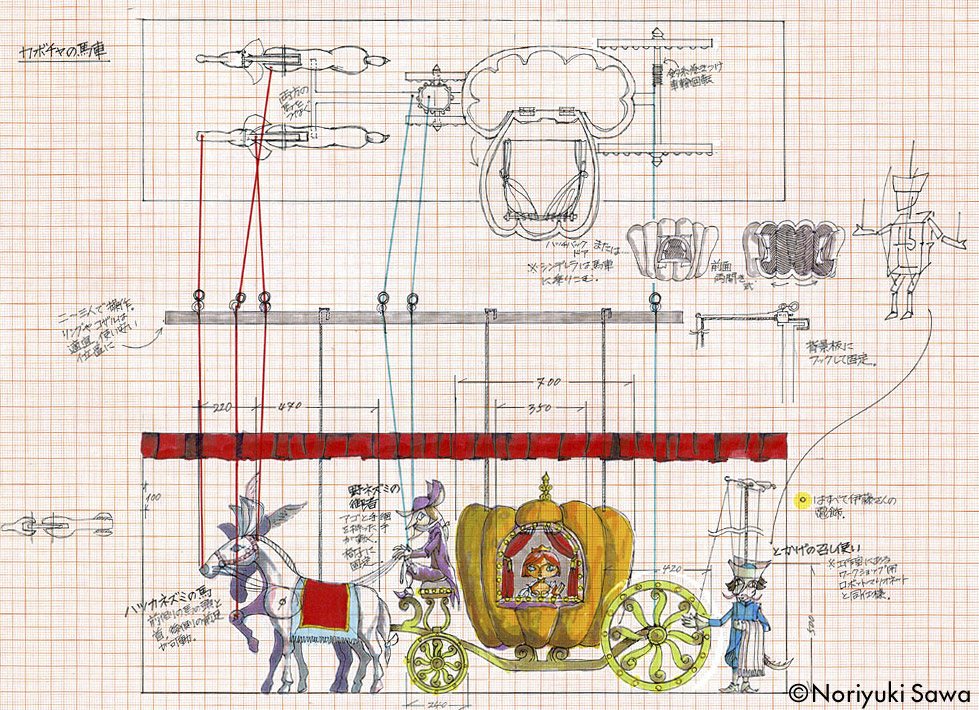

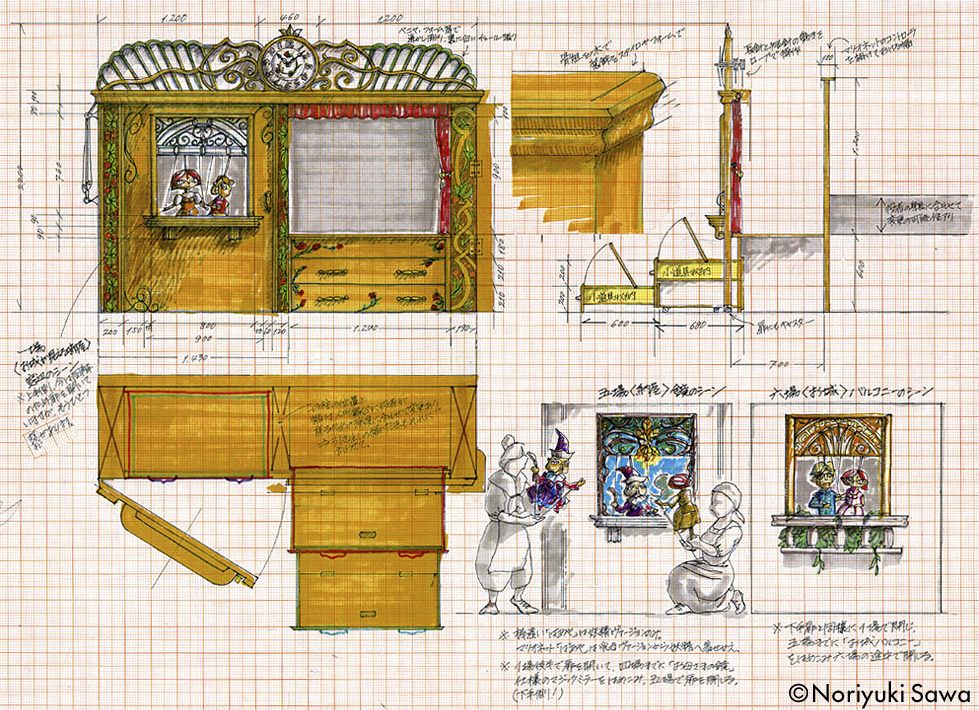

Visual sketches for puppets and stage arts

King Lear

(2004 at Aoyama Round Theatre)

The World premier in The International Scenography exhibition in Prague 2003 (PQ-03) Directed, designed and performed by Noriyuki SAWA

Music by Hirotoshi Nakanishi

Photo: Katsumi Takahashi

Related Tags