- Let’s start with your beginnings in theater in 1997, when you were still a student at Wako University and formed your theater company, Gotandadan. This was when you started your career as a playwright, producer and actor. Tell me about those days.

- I was bored silly in junior high and high school. Then I read that I could go see plays by small-theater companies for about 2000 yen, so I went to see them on my way home from school. I was amazed to see adults seriously at work on something so ridiculous. It opened up a new world for me. As a schoolboy I had wanted to be a novelist, but nothing I wrote was any good. I thought it would be more fun to do something with a lot of people, and I found an actors’ academy, Butai Geijyutsu Gakuin, near my high school that would teach me drama. That was how I began.

- In 2003, I saw Nagaku toiki (A Long Exhale). Your plays have no music or fancy lighting. There might be a futon or some other minor prop, but that’s it. I always thought of it as minimalist theater. Actors speak in normal voices, there is none of the loud, exaggerated speaking or gestures that one usually associates with small-theater productions. Have your plays always used this style?

-

My style has always been like this. When I first began acting, I practiced in my own room and performed in the corners of classrooms. If I stood up and ran around, the space would we lost. These constraints were part of the reasons my plays have never had much movement. I also knew that it would cost millions to create a stage setting if I set my mind to designing one. Rather than putting together something that was half-baked, I decided to limit myself to what I could do without spending much money. But that doesn’t mean I limited myself artistically.

For example, if you put ramen into an elegant bowl it doesn’t mean the noodles and the soup are going to taste good. There is plenty of time to think about the bowl and the toppings later. You’ve got to start out with the noodles and the soup. Once I ate something called Crab Ramen. It was a whole crab on top of a bowl of noodles. I couldn’t tell if it was crab or ramen [laughs]. There are plays like that. A story with a famous actor as topping. The focus is off. You can buy some great-tasting ramen for 500 yen. I figured that was where I needed to start. You need a script and some actors. Once those elements are in place and you’ve got something going, then you can start thinking about topping. I’m still in the process of writing plays, producing them, and getting actors to perform them. I still have a long way to go. - Have you ever worked with motifs that became the source of creativity, or had some similar experience?

-

Of everything I’ve ever heard, the things that have most moved me are my own dreams. When I was in high school, I had to get up at the same time every day, go to school, and exist within the narrow confines of school society. After I started college, I no longer had to get up in the morning. I didn’t have to go to class if I didn’t want to. That was when I started having dreams. Until then I had been so constrained that I had neither the ability nor the freedom to have dreams or to fantasize. I’d wake up and go back to sleep twice or even three times. That was when I finally started having dreams. I could never remember them afterwards, and they never made any sense, but they were so interesting.

When I was awake I couldn’t escape from reality, but in my dreams I had wild, unrealistic ideas. I was free. The value of anything creative, not just drama, but also novels and comic books, is the unfettered ideas they come from. This was my starting point for writing and putting on plays. I am still trying to do the same thing; put my dreams, just as I see them, on the stage.

Now that I’ve been doing it for ten years, though, I can see that even though I write scripts using an unconscious dream-like process, the act of producing one means communicating the story to actors in a logical manner. Actors then have the job of returning it to the realm of the unconscious. - It seems ironic that the result of all that unconscious work is having to make it all intentional.

- I’m getting better at writing. Unconscious elements are often hidden in the parts you don’t need. The better I get at writing, the more I can get rid of he unnecessary parts…. But then again, my work has a hatred of the refined, and I haven’t figure out how to resolve that conflict yet.

- Other than the change in consciousness, have you noticed any other changes over the past ten years?

- My motif has always been “life and death.” Until about five hears ago, I thought it was very nihilistic. Humans move towards their death from the moment they are born. But we don’t feel at the end of the day that we are twenty-four hours closer to death. We feel like we have lived for twenty-four hours. That’s an idiotically positive point of view, and it used to seem ludicrous to me. Now I think it’s wonderful. Writing plays has been my tool for thinking. The process of my flow of thought becomes a work of art.

- One of your representative works is Kyabetsu no tagui (A Type of Cabbage; 2005). The main character is a man who removes his memory from his head, and carries it around with him inside a cabbage. There is a female character who appears to be his wife. Her memory has been partly eaten by a worm, and her memory is more like a cross-section of the original. This is a play that has elements of the absurd. It makes the audience laugh and forces them to expand their own imaginations to their limits.

-

I wrote

Kyabetsu no tagui

in the form of a myth (one always begins at the same starting point but ends up in different places). I like to take pictures, but when I look at them later, I can’t remember what it was that interested me enough to want to take them. There is a clear difference between oneself in the past and oneself now, but there is no arguing that you are that person, and you have continued to be the same person ever since those days in the past. Just like a bracelet of Buddhist beads on a string, your memory is you linking different parts of yourself together.

So what happens when you pull your memory out later to look at it? It’s the connection to the past that makes you human. Can you call someone human if he or she has no past but lives entirely in the present? I believed a memory with layers like the leaves of a cabbage could be peeled away, one at a time, to reveal the unconscious of a man. Humans might be a life form no different from cabbages—that was the notion I built on. - I like the play Nagaku toiki about the man who can’t stop peeing. The performance uses real water and it floods the whole theater.

-

I had thought before about what it meant for someone to “get through” something. I almost never get angry, but it is an experience that everyone has, and I wanted to know what it was like to get through it. So I tried getting angry. I was sure I looked cool in my anger, but the effect was completely different and I had to laugh at myself.

I wasn’t very good at getting angry, so then I wondered about peeing. A main character who has been jilted will usually cry. But what if he peed rather than cried (to express his grief)? I pushed my character to the point where he was in danger of dying because he couldn’t stop urinating. If a person faced death like this, I thought they would probably be able to get through it and transcend it. I thought I’d look pretty cool if I was on the brink of death because I couldn’t stop peeing. I would be able to find nihilism by getting through it and experiencing death. That was the idea behind Nagaku toiki . There’s not just a man who has lost his love. There is also a father whose son has died, and he can’t stop peeing either. The pain of unrequited love and the pain of losing a child…. There is really no way to compare the two, but I thought it was interesting that there wouldn’t be much difference in the way a person expressed them. The two different types of sadness are profoundly different. Shouldn’t the way they are expressed be completely different, too? Because the expressions are similar, it just might mean that the sadness itself is also closer than we think. - Your most recent work, Idainaru seikatsu no boken (The Great Life Adventure; 2008), was also interesting. The younger sister of the main character, a young man, has died and he has ended up living idly with an ex-lover. The flyer for the play says, “We continue to live whether or not anyone else will have anything to do with us. This means that lives cannot be described as either grand or diminutive. Whether one lives holed up and idle or decides to pioneer a new frontier, there is little difference in the scale of the adventure.” Many of your plays are about characters like this who live rather anemic lives.

-

I have my own ideas of what a hero should be like, and these images are reflected in my main characters. My heroes are escapees from social pressure. We often hear people say, you shouldn’t try to escape, you’ve got to stand up and fight, suicide is just another form of escape. But I don’t agree. Escaping is just another way to live. Escapism should be viewed more positively. When life becomes too difficult and you find yourself being dragged down by it, all you’ve got to do is escape. It’s an important way to live.

Idainaru seikatsu no boken is based on my novel, Great seikatsu adventure (The Great Life Adventure). In the novel, the main character gives in once to nihilism. He manages to escape it by counting each noodle in a bowl of pasta. Escapism is a very positive skill.

I believe my heroes are influenced by their fathers. My own father never tried to encourage me. He drinks and sits in front of the TV watching samurai shows. I used to have problems with his lack of discipline, but now I admire him for it. The characters in my books are not perceived as escaping in as positive a manner as that, but I’m a half-step ahead of them, so it’s OK [laughs]. - In Ikiterumono wa inainoka (No One Alive Here?) for which you won the Kishida Drama Award, the characters die, one after the other, for no perceptible reason. It shows the variation of the stories of your plays.

-

There is meaning in changing the form of the same motifs when writing about life and death. If an artist draws a sunflower, it’s going to look different depending on the time, the place and the amount of light there is. It might be a bud or it could be past its prime. You never know unless you look at things from different angles.

My works follow several patterns. One is the “Road series.” It includes Nagaku toiki and Ie ga toi (Far From Home; the main characters are four junior high students on the road, and none of them really want to go home). A road is a public place, but when people gather on it, it turns into a personal space. That’s interesting. Then there is the “Room series” of plays that are set in something like a room, such as Doubutsu daishugo (The Large Gathering of Animals) and Futari iru fukei (Scenery With Two People). That is a category based on place. Then there are the categories of “Not Much of a Leap From Reality series,” “Great Leap Away From Reality series” and “Dream series.” Kyabetsu no tagui is in the Dream series, and Ie ga toi is in the Great Leap Away From Reality series. It’s not like I plan to write a particular series of plays, it just turns out that way. - All of your plays have elements of comedy. Do you want the audience to laugh?

-

I’ve never thought much about it. I have to admit that it’s easier for me when there is laughter. I said before that it was ludicrous that even though we are dying we feel like we are living. It’s basically absurd. To make a huge generalization, you could say that that is the true basis of all comedy.

I just remembered something. You could say that laughter is very close to aggression. Once, on TV, I saw people who believed in supernatural powers debating those who didn’t believe in it. At some point, someone came out and used his supernatural power to bend a piece of steel. Those who didn’t believe laughed when they were unable to explain how it had happened. That laughter sounded aggressive to me. It might be that I see manifestations of aggression in my own laughter and the laughter of others. I saw a documentary on Mother Theresa once, and it never showed her laughing. It might be that Mother Theresa experienced laughter as being linked to aggression and she refrained from doing it. - On another topic, a lot of your plays have female characters named Kanako. Is there a reason for this?

- It’s difficult to choose names for characters. Names that are cool sound narcissistic. I give names levels. Common Japanese family names such as Tanaka and Sato are level 1, Maeda is level 2. Senda [the interviewer’s name] has got to be about level 4 [laughs]. Given names are harder to divide up because they vary from year to year. Names like Kanako and Manami are easy to use; they’re always at about a middle level.

- Since 2005 when you made your debut as a novelist with Ai demo nai, seishun demo nai, tabi datanai (Not Really Love, Nor Youth, Nor a Trip), you’ve been nominated for a number of literary awards. So, you’ve made a name for yourself in this genre, too.

-

I’m ignorant about novels, so I can write as ridiculously as I please. No one can ever accuse me of doing something someone else has done before. At first, it was the same with plays, but as I gradually learned to tell which lines were good and which were terrible, I unconsciously began to censor the language I used. If I avoid using sensational lines, the play grows dull. If they sound sophisticated, all my plays will start sounding alike. I hear that lots of Koreans have plastic surgery. The more sophisticated people look with their surgically altered faces, the more they will all begin to look alike.

In the old days, work was refined according to different types of information, so they didn’t resemble each other, but in our day and age there isn’t much difference in the information cards we all hold, so the more we refine, the more things are alike. The only way to deal with this is to keep information out or stop refining our work. What I respect about otaku is that they keep most information out, and show their originality by sticking to only specialized information. - What type of director are you? There are some who really push their actors.

- As a director, I first have to believe in the play (script) itself. I also have to believe in the actors. I trust them to put everything they have into it. Even if an actor can’t do the part, I have to believe that it is still the result of his or her best effort, and I must accept it. Directors who push their actors are able to get superhuman efforts out of them, but nobody is looking for anything superhuman in any of my plays. I want the actors to show transcendence at certain moments, but basically, I want my actors to look like normal, everyday people on the stage.

- You also act in your plays.

- I’m always burdened with myself as the director, so when I get up on the stage, I’m aware of the audience and the other actors and influenced by them both. As an actor, I’m a little too sensitive to work with [laughs]. I do a good job at times, but I can’t keep it up. It’s okay to have one sensitive actor, but actors who are much less aware of things are stronger.

- The rumor is that you don’t have the ambition to move into commercial theater.

-

If becoming a major player means making more money, my family is already well off, so I don’t need to focus on that. I’m just not interested in major pieces.

People get impressed by loud sounds and beautiful lighting easily, and get excited just hearing a drum beating out a regular rhythm. It’s easy to be moved if someone comes up and grabs you by the collar and shakes you, but it’s just a form of catharsis, like giving someone an injection to make them cry. And that’s what ends up happening. Then you don’t need art. My plays might end up at the same point as others, but you can’t always be looking in the direction of the same exit.

Good stories and plots are not that complicated, and you can create a sort of pattern. You could even program them into a computer and have the computer do the writing for you. You might get something interesting out of it, but if you want to do it yourself, you’ll just be competing with the computer in terms of speed, and you won’t be able to win. The human unconscious is the only weapon that can beat a computer.

In Idainaru seikatsu no boken, the main character is sleeping next to a woman who may or may not be his lover. It’s hard to put into words, but there is something very human about it. You couldn’t express something like this in a major dramatic production where you have to be able to reach at least eighty percent of the population. With my plays, I’m aiming for the remaining twenty percent.

It’s the same with television series. You have to make the audience feel good, so you leave the uncomfortable parts to reality to handle and portray only the fun parts. But if you’re going to portray life and death, you’ve got to include the unpleasant parts and the parts that are irritating. The film director, Kazuo Hara’s documentary film Yukiyukite shingun (The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On; about a man who devotes years to a politically unpopular cause) made this clear to me. My impression when I saw it was that nothing could be this unpleasant. True art includes aspects that are painful and sad. That movie taught me that art has got to resemble real life. - Are you interested in performing overseas or in collaboration with foreign artists?

-

It would be great just to go on an overseas trip [laughs]. It would be difficult to get the subtitles right, but maybe works like

Idainaru seikatsu no boken

and

Nagaku toiki

, which are only about twenty percent speaking would appeal to foreign audiences who can relate to the lewd parts that anyone can understand. Improper subjects are ones that are easy to get audiences to share. In my workshop, I often use situations where someone is trying to hold their pee in. I have actors do an exercise where they are in a Ferris wheel trying to hold it in and they have to attempt to make a marriage proposal before the Ferris wheel goes around once. That’s an easy one for people to relate to.

A few years ago, I thought it might be fun to do Oyasumanasai (Good Night; a play about a man who gets lonely when his partner falls asleep, so he tries to keep that person awake) with a Japanese actor speaking English. I don’t suppose I’ll be able to do a collaboration, though, until I can find an artist who would respect it. - This is my last question. I’d like to ask about your performances this year. In June, your new work, Majiriau koto, kieru koto (Mixing Together and Disappearing) is going to be produced by Akira Shirai and performed at the New National Theatre, Tokyo. In September, you are going to be producing Aya no tsuzumi (The Damask Drum) from Yukio Mishima’s “Five Modern Noh Plays.” How do you feel about your first attempts to both let someone else direct a play of yours, and direct a play written by someone else?

-

As for the former, I tried to write without thinking about someone else doing the production, but it gradually began to bother me…. I make gaps when I write. Normal conversation lacks integration and begins to wander; it goes in directions I didn’t intend it to. When someone reads the script, I’m sure he will feel that it lacks coherence. It is left to production to give the piece the coherence that is not evident in the script. So it makes me think that no one but me can do the production. When I start thinking like that, it’s difficult to move on. I tend to write a rough draft and then begin to make revisions. I usually go through about fifteen drafts, but this time I’m doing even more, and I’m still not done.

“The Damask Drum” was an offer made to me by the theater. I had never read much Mishima before, but I’m interested in what I see as Mishima’s strategic nihilism and the way he gets it across. The piece has parts that laugh at love in a nihilistic way. I’m hoping to communicate that. There are many actors who I don’t know, and I won’t know how it will go until we begin to rehearse. Actors will only stretch in the direction they want to, and that might influence what I want to do with the piece.

Shiro Maeda

The view from an energy void Playwright Shiro Maeda’s Sense of Wonder

Shiro Maeda

Maeda was born in Gotanda, Tokyo, and graduated from Wako University. He formed the Gotandadan theater company in 1997 at the age of nineteen. The charm of his work lies in its naturally laid-back and amusing humor within a theatrical space. His plays Iya, mushiro wasurete-gusa (More a Forget-Me than a Forget-Me-Not), Kyabetsu no tagui (A Type of Cabbage), and Sayonara boku no chiisana meisei (Farewell, My Moment of Fame) were short-listed for the 49th, 50th, and 51st Kishida Drama Awards respectively. In 2007, he won the Kishida Drama Award for Ikiterumono wa inainoka (No One Alive Here?) This is a lyrical and humorous piece depicting death that grew out of a workshop involving the 17 actors who were selected from auditions, and for reasons never explained, all the characters die. It has been acclaimed as strict yet fresh theater of the absurd. Many of his short stories have been published in literary magazines, and several of his novels have been nominated for major literary awards, including Ai demo nai, seishun demo nai, tabi datanai (Not Really Love, Nor Youth, Nor a Trip) for the 27th Noma New Literary Writers Prize, Renai no kaitai to Kita-ku no metsubo (Splitting Up, and the Collapse of Kita Ward) for the 28th Noma New Literary Writers Prize and the 19th Mishima Prize, and Gureto seikatsu adobencha (The Great Life Adventure) for the 137th Akutagawa Prize.

Interviewer: Akihiko Senda

Gotandadan

Nagaku toiki

(A Long Exhale)

Premier: 2003

Plot:

Two colleagues are walking home from a drinking party after work, talking about nothing in particular. One of them mentions that he has recently been dumped by his girlfriend, and he turns to a fence on the side of the road and begins to pee. The pee begins dripping off the fence and onto the road (floor), but shows no signs of stopping. Passersby watch with curiosity—a grown man urinating in public, and the man himself becomes more and more uneasy when he can’t stop. Eventually his friend, who just happens to pass by and have brought a long a video camera, takes it out to record the event, when who should happen along but the peeing man’s ex….

Gotandadan

Kyabetsu no tagui

(A Type of Cabbage)

Premier: 2005

Plot:

A man’s memory has been taken out and transplanted into a cabbage. His wife has a worm in her head and is gradually losing her memory. A god wearing a short coat turns up. The man asks the god to get rid of the worm in his wife’s head, but the process goes disastrously wrong. The wife swells up to the size of the earth and can no longer be seen. The man now inside his wife hears her voice calling from outside. It is his memory taking in his wife’s memory, that is, the voice of the cabbageworm living inside the cabbage. Upon hearing his wife’s farewell, the weeping man begins peeling away the cabbage leaves.

Gotandadan

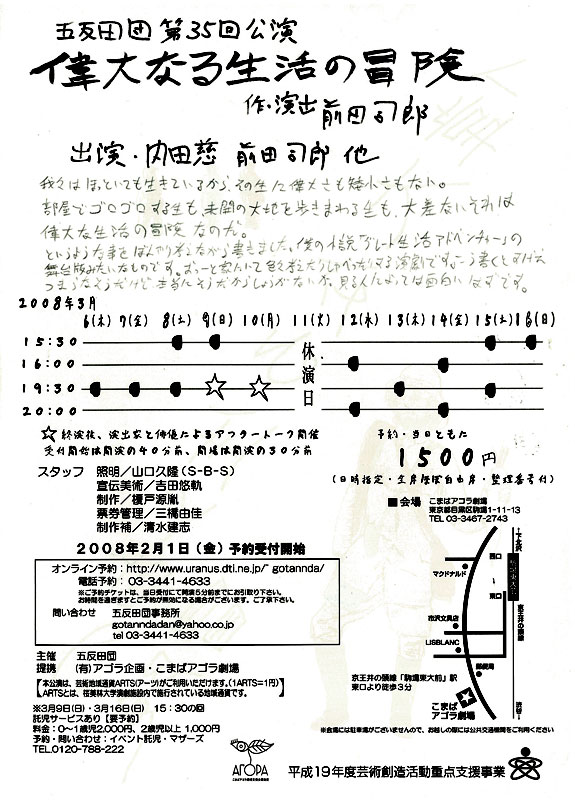

Idainaru seikatsu no boken

(The Great Life Adventure)

Premier: 2008

Plot:

Bedding is spread out in a room, and a man and a woman are sprawled out on top of it. The two are apparently ex-lovers, but the man is living with the woman, leading a life of seclusion. His only apparent goal is to win a videogame. Every once in a while, someone who appears to be a friend visits, and they have rambling conversations or play videogames. The man’s dead sister appears… perhaps he is having a dream. The woman he lives with orders him to leave. But the man doesn’t budge. In a way, it might even be considered positive…a “great life adventure, ” the way he continues to live his life doing absolutely nothing.

Idainaru seikatsu no boken ’s flyer (Maeda’s autograph)

“Series: Our Contemporary” Collaborations between Young Playwrights and Veteran Directors Vol. 2:

Majiriaukoto, Kierukoto

Dates: Jun. 27-Jul. 6, 2008

Venue: New National Theatre, The Pit Play by Shiro Maeda

Directed by Akira Shirai

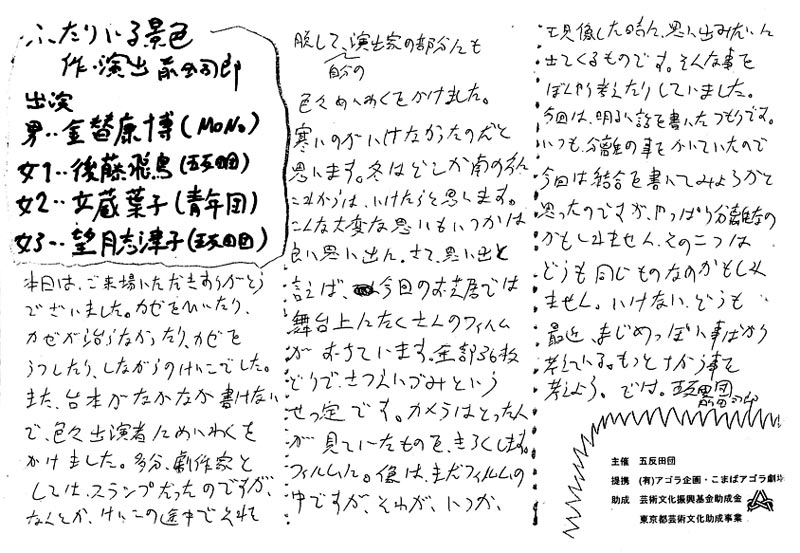

Flyer of Gotandadan’s 2006 production

Ftari iru Keshiki

(Production note by Maeda autograph)

Gotandadan production

Sayonara Boku no Chiisana Meisei

(Farewell, My Moment of Fame)

(Oct. 27 – Nov. 5, 2006 at Komaba Agora Theatre)

Synopsis:

A playwright calling himself “I” ( boku ) decides to donate one of the Kishida Drama Awards presented to him by his girlfriend to a poor country. While he is away, a snake living in his room swells up as it tries to swallow the girlfriend, the entire world, and by extension the play itself. These two symbolic episodes gradually converge arbitrarily to create a dreamlike rambling story. The author’s own experience of having twice been nominated for but failing to win the Kishida Drama Award also becomes a motif.