- I would like to begin by asking you how you came to stage Kafka works in the first place.

-

It started when the theater director of the Setagaya Public Theatre when it opened in 1997, Makoto Sato, asked me to come in as associated director. It seems that he had noticed my work using workshops to create theater productions, and the fact that I was holding theater workshops around the country.

When I began directing theater, I would not follow play script but prepare a number of different short studies, what you would call etudes in French, and act them out in the rehearsal studio in a workshop atmosphere in an effort to find how the text could be brought to the stage in the most interesting way. When I did the production Watashi ga Kodomo datta koro (When I Was a Child) based on Thornton Wilder’s Our Town and toured with it around the country, I tried a method in which we would tie up with the local public halls and hold workshops for the local citizens before the performance and choose several people from among the workshop participants to play roles as extras (people in the crowd) for the actual performances. It seems that Mr. Sato was interested in using that kind of activity and creative method in his new theater.

So, I became involved at the Setagaya Public Theatre doing things like workshops for high school students. At the same time I was asked to submit a report about the kinds of plays the theater could add to its repertoire. I believed that Setagaya Public Theatre provided an opportunity to do things that I couldn’t do with my own company and to try new things I hadn’t tried before, so I suggested doing Brecht and Kafka. The first play to actually be done from that proposal was Brecht’s Life of Galileo .

Kafka’s The Trial and The Castle had already been made into plays abroad, but Amerika had not, and therefore it had not yet been labeled “theater of absurd.” It is a story that is interesting in its Bildungsroman (cultured novel) aspect while also presenting a very Kafka-esque world. I wanted to spend some time and work on this project in a workshop atmosphere to see how the actors would read this novel from the standpoints of the characters’ movements and relationships. It was in my fourth year as a director (at Setagaya) that the plan for this project was finally approved and we were able to do our production of Amerika . - You started out as an actor for the Shingeki (New Theater) company, Bungakuza. At the time in the early 1980s it was the height of Japan’s small theater movement and the Tokyo theater scene was a patchwork of many different styles and forms of theater. Within that context you started your own company, Gekidan MODE and began creating productions using the workshop format. How was it that you originally came upon this method of working through workshops.

- Japanese acting takes on a number of different forms depending on the writer, the director and the company. But, if you were to divide it into two main types it would be the natural acting style of the New Theater companies like Bungakuza, which I belonged to, and that of the Angura (underground theater) movement that criticized our style. When I was attending Hirosaki University the upperclassmen in our university’s theater club were already saying the New Theater was no good anymore, but I hadn’t even seen any New Theater at that time. The attractive movie actors at that time like Yusaku Matsuda, Kaori Momoi and Yoshio Harada were all originally New Theater actors, so I thought I should get to know it a bit, and that was the kind of half-serious attitude that I joined Bungakuza with. But I already had the underground style acting habits of typical college theater at the time, so when I was a trainee at Bungakuza I used to take a semi-crouched pose and really shout out the lines (laughs).

- A semi-crouched pose and shouted lines would be an “Angura” (underground) acting style. Did your instructors point that out or criticized you for that?

- Yes. I was told to try to speak a little more naturally. The representative actress in Bungakuza at the time was Haruko Sugimura, and under her were actors with refined acting styles like Kiwako Taichi and Kazuo Kitamura. Seeing them firsthand, I couldn’t help but appreciate how skilled they were.

- In other words, your experience there was one of re-discovering natural acting and the good aspects of it?

-

Yes. I wasn’t actually good at it myself, though. Even in Bungakuza there are people who are good at it and people who aren’t, and I belonged to the latter group. But, discovering the differences between good and poor natural acting styles was interesting for me. Although she would be acting in a natural vein, however, Kiwako Taichi might suddenly shift gears to a different level of concentration and her acting would change from that point into something that wasn’t natural. Her acting and her methodology when she was in a gear like that seemed to me to be no different from that of the great Angura actresses like Lee Reisen and Kayoko Shiraishi.

The premier New Theater actress at the time, Haruko Sugimura, was the same. Even though she would point out to the younger actors, “You’re not being natural,” her own acting went beyond the natural. Even though she was past 70 at the time, she played the part of a 17 year-old girl in Onna no Issho (The Woman’s Life). That is certainly not natural. - She went on to play a girl at the age of 87.

-

I even thought it was close to the butoh dancer Kazuo Ono dancing in the costume of a young girl in his old age. Sugimura would play the role of a girl using an artificially young voice into her 70s, but in the end, from the second to last time she preformed that role in

Onna no Issho

she used her own low voice. I saw that performance at the Toyoko Theater and it really moved me. When I told her about it, she said, “I have been saying for decades that you don’t have to make a false voice, but I only just now have realized that for myself.” I thought that was incredible.

There were amazing actors like that in New Theater and, on the other hand, among the actors raised in the company of Tadashi Suzuki, who was a strong critic of New Theater naturalism, there were people who became too entrapped in a particular form of style. And, that fact made me think that it was possible to be just as critical of Angura acting. That is what brought me to the conclusion that there was a need for everyone to feel out their and the others’ acting in studio rehearsals first, and I believe that in turn led to my workshop approach. - You have just mentioned how incredible it was watching Haruko Sugimura. Was it like experience the primal ground of acting, or perhaps one could say the magic of moments, for you?

-

Yes. As a young aspiring actor at the time, those were the kinds of things I was most interested in, and then after that my interest began to shift gradually toward directing. I became interested in how an appealing performance was created. Was it method? My interested began to shift toward what from the actor’s perspective would be called a re-examining or re-evaluation of one’s acting.

Around the time I started my MODE group, there were a number of theater companies in Tokyo that were using an improvisational method and we got an actress from one of those companies to participate in one of our productions. But, part way through the preparations, she started to get nervously distraught because the way of working was so different from that of the director of her company. She asked me when the lines and the acting would be finalized. I answered that we didn’t finalize them and I asked her how they did things in her company. She said that the improvisational part was only up until a certain point and then the rehearsals would be taped and, from those tapes, they would finalize the lines and the acting. When I told her that nothing was finalized in our plays until the final day of performances, she said, “Then I’m quitting now.” (Laughs) - We hear that in your workshops you act out scenes based on a variety of materials, such as a fragment of a newspaper article or a scene from a Chekhov script.

-

Yes, for example, in our play

Kaisha no Jinji

(Company Personnel Affairs), we took the final lines of an illicit love affair between a female office worker and her boss, in which the woman finally dumps the man, and made it the episode to work on in one of our workshops. We borrowed the setting of Chekhov’s

Uncle Vanya

to create a scene. In the early years of MODE we would change that roles that the actors played every day so that the actors had to have the entire text in their mind all the time. That required a lot of rehearsal time.

There was one actor who had only acted in Shogekijo (small theater) plays in the past and he had trouble delivering Treplyov’s lines from Chekhov. Then I drew on his own experience and told him that these lines are the same as rebelling against the present theater world, so with that in mind, try saying it all in your own words. After that he said, “Until now I have just been memorizing the script verbatim, but now I think I understand.” And then he was able to speak the lines wonderfully. - Does “wonderfully” mean naturally?

- You could call it natural, or I would say it is when it sounds like the actor himself is speaking. Not like he is speaking as Chekhov’s Treplyov is but as if he is borrowing Treplyov’s words to speak his own mind. That is what I believe acting is about. The function of the workshops is to get the actors to speak as themselves and that is what the workshop space is for.

- Can we consider the workshops you were doing at Setagaya Public Theatre to be an extension of what you had done at MODE?

-

There is a continuity but the participating actors are different. The fact that what we are doing at Setagaya are productions produced by a theater has brought in a new group of actors who are interested in participating in workshops even if they don’t know my work. I was glad to see actors who have had a career in the so-called Angura Small Theater coming to participate. It is a fact that many of the people who started the Small Theater Movement in the 1960s had training in New Theater before that. For example, the butoh artist Akaji Maro spent some time in the New Theater company Budo no Kai, and when he has had a few drinks he will say, “Hey, I’m not an Angura actor, I’m a New Theater actor.” It is easy for me to work with people like that. Easier than it is to work with people who have no New Theater experience, actually.

At Setagaya Public Theatre I first directed Chekhov’s Platonov and then Brecht’s Life of Galileo . Because there were some very busy actors taking part in these productions, even if I wanted to do workshops, it was hard to get everyone together. We continued to do workshops with the actors who could attend, but what we did in them was not to work with the actual text for the play but things like working on a scenario by Godart. We played around with typically philosophical Godart text containing a direct connection to acting theory, such as, “You are an actor aren’t you? Say the lines you said in yesterday’s play again now. How are they different from when you said you loved me?”

Of course there will be cases where we could do workshops for a year and we still couldn’t bring out the best of a given actor with this method. When that happens, we have to make sure that that actor doesn’t stand out as different from the rest. It was during the workshops that I came to think about the necessity to make certain allowances in the composition and directing of the play in order to make sure that the actors can be in the same unified world as much as possible.

And it was as an extension of this working process that the idea of doing a Kafka play, as I had originally proposed, came to mind again. - Can you tell us in specific terms what kind of things you tried to do in your workshops while preparing to do a Kafka-based play.

-

We took a year working on

Amerika

and that included four or five workshops of a week to ten days. Rather than working intensively over a short period, we adopted a method with intervals in between where everyone would return to their own companies for a while and then assemble again to pick up where we left off in the previous session. In the Japanese theater system, no matter how finely you cut. So, I think it is meaningful that we were able to do that.

Actually, with Amerika there was an actor who had been decided on to play the part of the young Karl, but just at the time when the workshops were finished and we were ready to begin the serious rehearsals, we got word that he would not be able do the part because of an injury. In the workshops six or seven people, including some women had been doing the part of Karl, so it occurred to me that we could change the approach and have several actors play the part. And I believe that in the end it turned out to be a more interesting staging than if only one actor had been playing the role. - A case like this where a mishap can lead to fresh new ideas, we are reminded once again just how fascinating an art form theater can be. How did you conduct the auditions for Amerika ?

-

First of all I gathered a number of actors who had worked with me before. Then we held open audition. We reviewed all applications about 200 people who came first, and we reduced the number of potential candidates until we had about 50 people. Then we divided them into small groups and had them begin actually acting out of fragments of Kafka’s novel. The purpose here was not to check the quality of their acting but to see if they were suited to our working method or not. We wanted to choose actors who could find interest in the process of reading the original text and then imagining ways a scene could be staged and then trying a number of different patterns of acting it out, rather than the usual process of memorizing a script where the conversation is written out as spoken lines and the rest is described in stage direction notes. In such a method, the more patterns they can come up with the better. We were not looking for a correct answer, we wanted people who were not afraid of failure and were willing to expose themselves to uncertain situations and try new things.

When I say “expose themselves,” I mean allowing themselves to get into a particular mode they are trying. No actor can really expose their naked self completely. I often say that it is OK if everyone in a group that is trying out one of these etudes finds it’s not interesting. The important thing is that the actors are aware of what has happened and share a consciousness of it with the others. At the end of the audition process we selected 26 people to go into the final series of four workshops.

Another requirement for the actors was the ability to read the original book. In the case of Shakespeare, you’ll get by because everything is there in the words of the dialogue, even if you don’t read it with much emotion. But Kafka is different. There is no single interpretation in Kafka’s writing. For example, Josef K. may say one thing, but then his actions show something else, so there is an element of contradiction. What we needed was actors who could find delving into these ambiguities interesting. - It is certainly true that Kafka’s writing is shrouded in mystery. There is no single, consistent storyline from beginning to end.

- In Kafka’s writing he doesn’t use expressions like, “he did such-and-such as if ….” For example, he will write, “He jumped back in surprise.” He doesn’t write, “He was surprised so much that he nearly jumped back.” He has his character actually jump. What is interesting is what you might call a caricature aspect of the kind of off-the-wall strait-forwardness you might find in slapstick. So what you need is not the kind of actor who will act a natural impression of surprise without jumping back but an actor who will actually try jumping back. And it is not just with regard to Kafka. If the text says “He stiffened up like a chair on the floor,” we are interested in the kind of actor who will actually try to become a chair.

- In other words you were seeking new discoveries by working with Kafka’s original text?

-

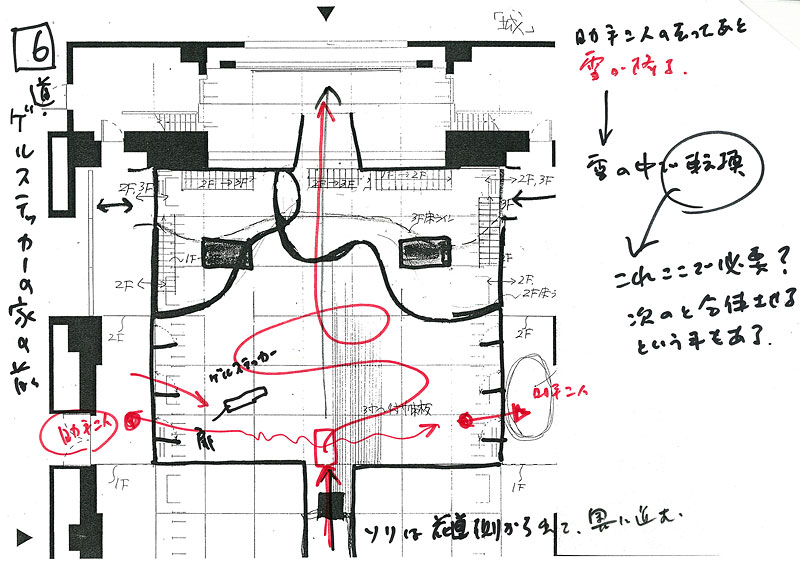

Yes. And as we do that I am thinking about the general allotment of roles and I get a vague overall picture in my mind of what the final composition of the play will be. I pick up the scenes that look like they will work well on stage and hand-write a rough outline of the play in diagram form.

And while thinking about how to best piece the parts together, I divide the actors into groups from around the third workshop with the roles assigned in each group and have them actually perform by group and show each other their versions. Although the text they are working from are the same, the actors in one group may deliver lines with very little movement, while another group will do the opposite, with more action than words. The performances of the other groups naturally influence them as they search for a variety of methods of expression. And as I watch this process I study the possibilities for viable scenes.

I also try out general images at this stage about what the set and stage art should be like, whether a large space is best or a small, confined one. I have the actors run through scenes while seeing what it is like if ten people or so are confined in a small 2.5×2.5m room, and then try it in a large space. These four preliminary workshops offer that kind of opportunity to try out a variety of “sketches” for how the play can be staged. - Kafka was writing novels, not plays, so it must be hard to translate his writings directly into theater as they are. How do you make plays out of his works?

-

First of all, I break the long Kafka novel into blocks. And these blocks do not necessarily coincide with the chapters of the novel. A scene of the final play may consist of the last one third of a chapter stuck onto the following chapter. Or I may take what were four or five different interior scenes in the original and lump them together into one scene that I may set in a pub. I show these compositional ideas to the actors in my outline diagram form, then the actor chose parts from these scenes that they feel would be interesting when dramatized and they try acting act them out.

There are cases where they choose scenes in the novel that have no conversation at all and they transliterate it into dialogue in order to create a scene that can be acted out. In a scene where middle-aged men are drinking in a pub, our older actors with more life experience can improvise appropriate dialogue, but younger actors have a hard time. In a case like that, I may give the young actor a memo telling him or her to try making up some lines where they are badmouthing their boss at work. - In the end, do all these fragmented scenes come together into one finalized play script?

-

You can’t really call it a play script because I just make cards about the size of a postcard for each block of the play telling what characters appear, what the set is like and what events happen. For example, with

The Castle

I had about 50 block cards at first, and after throwing out the ones that looked like they wouldn’t work on stage and combining some others into one scene, I ended up with about 30 cards. For

The Trial

I had a block that I titled “Josef exhausted at the bank.” It was a scene that in the original novel involved only Josef, the bank manager and the assistant manager, but as the workshops progressed I wrote notes that I wanted to try it as a scene with seven people, including other bank employees. Or, there was a scene that was an interior scene in the original but I got the idea during the workshops that I wanted to try it as an outdoor scene on a town square with a group of people in the background.

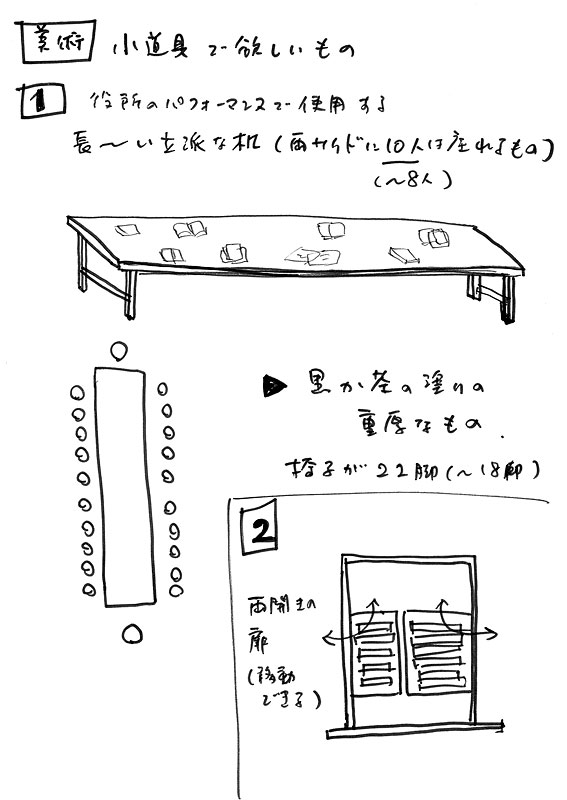

I also write down notes [on the cards] about the props to be used; how many tables and chairs, etc. And, although I am not good at drawing, I do simple sketches of the shape of furniture I want. Then I lay out all these cards on a big table in order and do a variety of simulations. Doing this, I see patterns, such as “If we have another bank scene here it will be too heavily repetitious, so let’s eliminate that scene.” I do these simulations over and over. That is how I put together the scenario for Amerika , but with The Castle and The Trial I ended up finding that using same story line as the Kafka original was the most interesting, so I didn’t change the order of events. - Do you write down on the cards things about the actors’ movements, such as, “A enters from the stage left, so we’ll have him come out and do such-and-such at this point.”

- I don’t do much of that kind of notation. I give those kinds of directions in the rehearsals. I think about those things in the final rehearsals once the set plan has come together. Although I do have general images in mind, such as when I want an actor to come out from the back of the stage and when I want them to come out from the wings.

- Did you use this card method when you were directing at MODE?

- Yes. The idea was inspired by the “Mass Image Method” that the critic Takaaki Yoshimoto wrote about. In his book he wrote about analyzing social phenomena using images. My directing assistants and staff say that it would be better to put everything in the form of a play script [booklet], but it is easier for me to think in terms of image cards and diagrams. I use different sizes of cards; I will use a small card for a scene that may last ten minutes and a large card for one that lasts 20 minutes. When I line these cards up in the order I am thinking of for the play and see a place where too many large cards come in succession, I realize that that section of the play will be too heavy, so I change the order. In that way I create the balance and rhythm of the play. I am told that this process is similar to how music is composed.

- Now that you mention it, it certainly does seem to me that your plays have a musical-type composition to them.

- When I decide that I want some particular kind of movement or a scene with a particular image at some point in a play I may ask a choreographer Shigehiro Ide to choreograph something for us and make it purely a dance scene instead of a real drama scene. But after it is choreographed and I see the final result in the context of the overall flow of the play, I may decide it is too heavy and end having to say, “I guess we don’t need it after all.” (Laughs) There have also been cases where I completely forget about a scene that was interesting when we first read it in the early stages of the workshops until one of the actors asks “Aren’t you going to use that scene that was interesting back in the workshops?” (Laughs)

- So, that is another aspect of the Matsumoto “card directing system”? (Laughs)

- I call it a “composition chart.” Since there is no play script in booklet form for the staff to refer to, I have them take down the necessary directions in a notebook with the music and lighting cues that will be needed. When we were working on The Castle and The Trial the directing assistant went to the trouble of typing everything into a word processor and printed out something like a play script, but the contents would have to be changed almost every day. I’d have to say things like, “Sorry, I cut this part. Please tear it out.” Or, I’d be asked if they could consider some section of the composition finalized and I’d say OK, but then after thinking about it overnight I’d decide to substitute it with a different scene make-up. It was with The Trial that I gave the staff and the actors the hardest time. I didn’t realize until the final dress rehearsal that the play’s running time was too long, and there was no time to correct it. So I kept working on it even after the performance run began. It was running as a double bill with The Man Who Disappeared ( Shissosha ) and I re-worked the composition of The Trial during the performance of Shissosha , cutting three scenes that shortened the production by 20 minutes.

- Is that how it happened? I remember commenting in a year-end review that year in a magazine that it would have been better to shorten a bit. And I guess I went on the wrong night (laughs).

- For example, in the scene where Josef K. and his lover the dancer are at a pub and they happen to meet a detective they know, there was originally a dance scene there. I took that out. The trouble is, however, when you take out one scene, you have to change everything from the set changes to the quick costume changes. After changing the make-up of the scenes I go to the my assistant director, the stage director and the costume staff to discuss with them how much we can get done, and they might say that the actors have to help with the set change so they won’t have time to change costumes. So then I have to go back and change the make-up of the scenes again. Of course the actors aren’t expecting the play composition to be changed suddenly when we have already been through five evenings of performances, so they are understandable surprised when I show them the new composition chart. I know that I really make things difficult for the actors and the staff. I usually prepare about twice the number of scenes for a play than will actually be performed in the end. In the case of The Trial , the first full rehearsals ran for five hours, but in the final performances I had that down to 2 hours and 55 minutes.

- Is it a process of gradually cutting out the unnecessary parts?

-

As we work, the actors must be thinking, “This part will probably be cut out in the end anyway.” I think they are probably predicting along the way which scenes will eventually be cut. Usually I start cutting scenes from about two weeks prior to the opening night. With

The Trial

, it was five hours long a month before opening and I started cutting early. But it wasn’t until we got into the final dress rehearsal that I realized I hadn’t cut it enough. And it is not just a process of cutting out scenes that aren’t necessary. For example, a 15-minute scene can sometimes be condensed into a 10-minute scene and made simpler. I feel that can also made the scene communicate its point better.

I’m told sometimes that if that is the case, why don’t I write a script that way in the first place. But I can’t do that, because that would undermine my fundamental workshop type working method. - Normally, if one is doing a Chekhov play for example, there is the script and you stage a production based on the script, but in your case you have the actors act everything imaginable and then cut away what you don’t need until the record of that process becomes the final equivalent of a script. It certainly would be natural for your actors to get a bit angry (laughs).

-

Yes, that’s true (laughs). Since part of the interest of Kafka is the way the characters talk on and on about unrelated things or insignificant things, I would like to leave in some of those parts. But I work together with the actors to cut out the things that don’t need to be said twice. The things that emerge from that process become more interesting. From what I hear from people who have participated in the contemporary dance artist Pina Bausch’s workshops, it seems that she has the dancers work a great volume of etudes into dances and then eliminates most of them in the end. Even if a particular scene may be cut in the end, the physical experience of having worked on it and thought about it will definitely remain. I believe that concept is close to what I am doing.

I want to spend time on this process, but in Japanese theater the most you can expect to be able to use a theater for dress rehearsals is the two days before the opening, so you are really going into the performances with a lot of uncertainty. And in my case I want to start cutting things and introducing new scenes after seeing the dress rehearsal. And, it occurred to me that perhaps a public theater could offer an environment where I could have that freedom. - In the plays you direct, I find very effective the dance pieces that appear between the acted scenes or the music, like the brass music you used in Amerika that was reminiscent of the music in the movie Underground . Can you tell us where these ideas come from?

-

The dance pieces like the one in the dream scene before Josef’s execution in

The Trial

, or the scene where the woman carrying a bucket crosses slowly through the crowd of people on the street, these are things I choreographed myself. I don’t think of it as dance. I am just trying a variety of methods to achieve the kind of theater (stage) space I would like to see.

As for the music, since my MODE days I have always chosen all the music myself. So the sound people usually dislike working with me, because I don’t let them choose any of the music (laughs). In Amerika I used the Jewish folk music performed by an ensemble known as klezmer. I had people buy CDs of klezmer music for me overseas, and I listened to about 50 in all to find pieces that interested me. During the workshops I tried playing this music and having the actor perform with it as the background music.

When I am directing I always have an audio set next to me so I can play different pieces of music and see if it fits with what is being done on stage. The music itself has a composition, of course, so you can work around the image of filling the stage space only with music and lighting during the prelude portion of a piece of music and then have the actor(s) come our on stage naturally as the music enters the main theme and have them disperse as the interlude starts and at the finale have them disappear. And you can work dialogue into the whole at different places.

If the music matches the scene well, there are times when no spoken lines are necessary. If it is a scene that expresses grief, and a sadly emotive piece of music is playing, all the actor may need to do is to stand there. An actor who can feel this knows that words are not necessary. And there are cases where this can stimulate the imagination of the audience even more than words. In contrast, there are times when music can be use to implant an image in the actor and then when the sound is stopped at some stage the actor can remain silent and the mood continues. Even without the sound, the image already implanted by the earlier music remains inside the actor and it can have the power to make the actor a different figure, even if he or she is just sitting still in a chair. - It seems that music, art and other elements like lighting all have equal value for you and you bring them all together into one image. From the standpoint of the audience, your plays add scenes with psychological or subconscious elements that we don’t when just reading Kafka as literature, and the resulting “dramatized Kafka” is very interesting. Now that you have done dramatic productions of this much Kafka, what do you now find interesting in Kafka, and in what ways?

-

Some readers of Kafka say that my plays add humor and sexuality that isn’t in the original Kafka, but I don’t think that is true. I believe that there are sexual images and lots of humor written between the lines in Kafka’s work. In the way that Kafka has been read so far in Japan, I feel that perhaps this element has not received enough attention. But in dramatizing Kafka, I have found this aspect to be a very interesting. I have realized that the reason I didn’t find

The Castle

interesting when I first read it as a young man was because I read it only in terms of concepts and wasn’t able to read those other aspects between the lines.

I believe that humor is essential in theater. If you don’t have a certain amount of experience in love and experience in the ways of society, you can’t read the humor that is written into Kafka’s literature. I now find it very interesting and humorous when characters like public officials or lawyers appear in Kafka’s stories and they hold truly ridiculous principles in their jobs. But what may appear at first as nonsense are actually the kinds of situations that actually exist in society.

Also the way Kafka depicts sexuality is interesting too. There is the desire for love and there is the desire for physical intimacy, and the two do not necessarily coincide. There is a lot of unrequited love and unrequited sexual desire in Kafka’s works. In the staging it may take the form of a character leaning on the woman and caressing her as he delivers the line, “The trouble with your lawyer is …” In other words, when it is stage you can see that gap between emotional and physical love clearly. - There surely are many instances when seeing things acted out physically by the actors brings a realization of what was actually intended between the lines.

-

We can perhaps see Kafka in theater as a reflection of ourselves today. It may not be a complete baring of ourselves, but there are some graphic images we can get.

Of course we are also drawn to the literary themes Kafka deals with. In my staging of Amerika and The Castle I used a subtitle projection system to introduce what we might call some main Kafka aphorisms. With regard to questions such as, “What is the self?” Kafka describes the solitude of the individual with expressions like “Looking up at a high window in a solitary prison cell,” which is a kind aphorism that we may or may not provide us an understandable reason.

Also, Kafka’s descriptions of the visual aspect of people’s appearance, clothes and things like buildings are very detailed. It is interesting to try to imagine the images Kafka is describing. It brings new realizations about new perspectives for looking at things or how the streets of town appear when you are in a certain mood. I was talking to one theater director who said that showing that kind of appearance is possible in movies but it is probably difficult to achieve in theater. But, I think it is possible in theater too.

In Kafka’s novels there are many scenes of sleep, and passages where he describes people waking up to find that things have changed. A famous example is in the beginning of The Metamorphosis where the character wakes up in the morning to find that he has changed into a giant vermin. And then he writes, “It was no dream.” He doesn’t write, “It was a dream,” he writes “It was no dream.” I believe this is what makes Kafka so interesting. - You have also staged a version of The Metamorphosis . When the main character wakes up as a vermin, you didn’t use an insect costume of anything, but just showed the character as a normal human figure. But the people around him begin to treat him as an insect. It was a fearsome theatrical device in which, as the people around him said, “You are a vermin,” he actually came to look like an vermin. I felt it connected to contemporary social problems like bullying as I watched the play. It is very Kafka-esque. If we were to be explanatory, we could say that it connected to the Holocaust and to discrimination, ethnic cleansing and other forms of annihilation of those who are different from oneself. It shows these tendencies in a very real way.

-

I thought from the beginning that it would be OK to have the character Gregor Samsa just lying there in bed in his pajamas. I saw a tape of Valery Fokin’s theater version of

The Metamorphosis

and he had the actor appear in the form of vermin and the scene where he is on the bed and can no longer move, I found it very distasteful. The deformity and actors movements were like that of a disabled person, and in the end he can no longer move and is disposed of. That appeared to me to be very discriminatory in nature. So I definitely didn’t want to stage it like that.

I preferred to use and approach similar to the simple structure of Noh and Kyogen theater, in which an actor can come out and just say, “I am a mountain monk from around here,” and from that point he is a mountain monk. The Metamorphosis was published while Kafka was alive and he requested that a vermin not be used in the illustrations for the book. The final print used as the illustration for that scene was one of family members peeking in the room where he lay and screaming in alarm at what they saw. It doesn’t show the vermin itself. There is much speculation about what kind of vermin or insect it was, but nothing specific is written to describe it. So, we wonder if someone really did undergo a metamorphosis. It may not have been Samsa but his family that underwent the metamorphosis.

Osamu Matsumoto

The world of director, Osamu Matsumoto - Staging Kafka with his unique style with workshops and composition cards

Osamu Matsumoto

Matsumoto was born in Sapporo in 1955 and is the leader of and director for theater company MODE. After performing as an actor with the Bungakuza, company for ten years, he founded his own thatear company, MODE, in 1989. There he won acclaim for adapting and directing works by foreign playwrights like Chekhov, Becket and Wilder as contemporary Japanese plays. He has also collaborated actively with leading contemporary Japanese playwrights including Miri Yu, Yoji Sakade , Oriza Hirata, Masataka Matsuda and Akio Miyazawa. From 1996 to 1998 he served as full-time director of the Hokkaido Theater Foundation. For five years from 1997 to 2001 he served as associate director of the Setagaya Public Theatre and mounted there in 2001 a highly acclaimed production of a play based on Kafka’s Amerika that was brought to stage through a year-long process of auditions and workshops. A revived production of this play in 2003 won Matsumoto the Yomiuri Theater Grand Prix Outstanding Work Award and Outstanding Director Award, as well as the Senda Koreya Award of the Asahi Arts Awards. In 2005, his production Shiro based on Kafka’s The Castle again won him the Yomiuri Theater Grand Prix Outstanding and Outstanding Director Award Work Award. In addition to his series of works based on Kafka, his notable productions have included Watashi ga Kodomo Datta Koro (Yomiuri Theater Grand Prix Outstanding Work Award and Outstanding Director Award), Puratounofu (Yuasa Yoshiko Award) and Galileo no Shogai . He is also an assistant professor of the Art Dept, of the School of Literature of Kinki University.

Interviewer: Yoichi Uchida, journalist

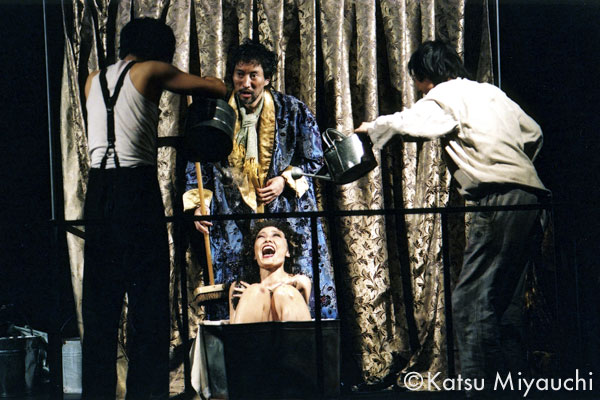

Setagaya Public Theatre production

Shinpan

(The Trial)

(Nov 15 – Dec 8, / Setagaya Public Theatre)

Written by Franz Kafka

Directed by Osamu Matsumoto

Photo: Katsu Miyauchi

Setagaya Public Theatre production

Shissosha

(The Man Who Disappeared)

(Nov 15 – Dec 8, / Setagaya Public Theatre)

Written by Franz Kafka

Directed by Osamu Matsumoto

Photo: Katsu Miyauchi

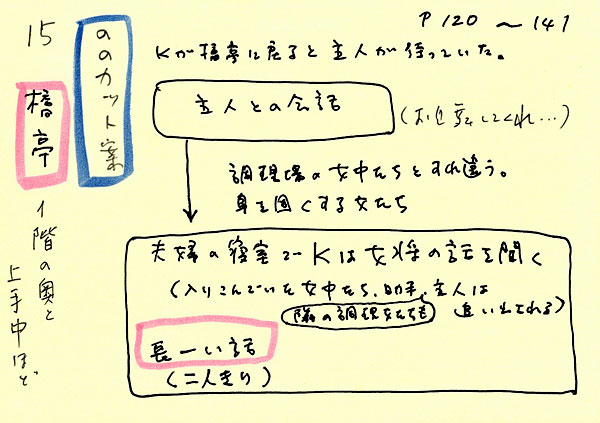

Samples of the director’s cards for The Castle

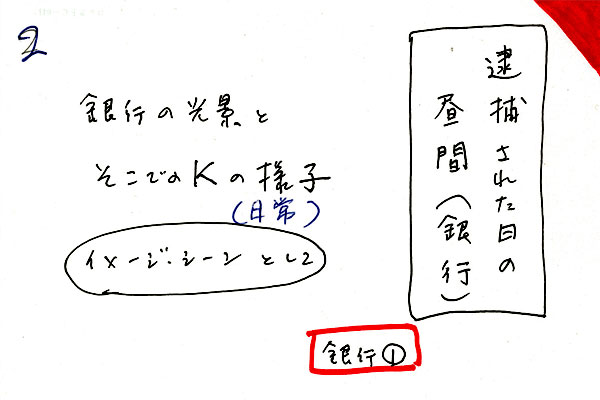

Samples of the director’s cards for The Trial

Samples of the director’s cards for The Castle

Related Tags