- You are a former member of the institute affiliated with the theater company “En.” Considering the fact that most companies in the small-theater scene tend to be made up of people from the same college theater groups, it seems a bit unusual that you belonged to a New Theater company like En.

-

Let me start from the beginning by saying that I began theater when I was in high school. However, since it was the drama club in a boy’s school, I was the only one who was really interested in doing theater, while the rest of the club members joined for less reputable motives, like the fact that the club room had a door that could be locked to keep them from being observed. Since it was a high school with an affiliated university I could have just gone on to that university, but since it wasn’t very active in theater, I decided that the best universities to go to for theater were probably Waseda and Meiji. I took the entrance exams and got into Meiji.

However, it turned out to be a time when the Meiji student drama club “Daisan Erotica” had just gone independent and most of the best actors had gone there, so we were left with a lack of good members. With nothing better to do I agreed at the suggestion of an upperclassman to join the film research club, but there were some people who wanted to do drama and they asked me to be one of the actors—the director at that time was Yuko Matsumoto, who is now active at Bungakuza—and I later wrote and directed a work with the people I met then.

That turned out to be such an amateurish production that I realized the limits of working only with people of my same age and that led me to decide to join a theater company with people of all ages and learn from the beginning how plays are created. So, I took the exam to enter the company in my junior year of college. - Was En the only company (which has an affiliated institute) you took an entrance exam for?

-

In fact I also took the exam for the “Ninagawa Studio” group for young actors started by the director

Yukio Ninagawa

, but I wasn’t accepted. I was so nervous at that exam that I couldn’t remember any of the lines when we were given a script of a lay at random and asked to act it out in our own way. I was desperately trying to remember the lines and I ended up acting it out so slowly that Ninagawa told me, “It you act that slowly the audience will go to sleep, stupid. You can leave” (laughs).

Thanks to that experience, I went into the entrance exam for En institute thinking that I could never be as nervous as I was that time with the Ninagawa Studio exam, so I ended up not being nervous at all, and everything went well. - Why did you choose En?

-

Because it was a company with a variety of different types of directors doing completely different kinds of productions. It just happened that during the year I was thinking about taking the exam to enter a company En was doing works by the popular small-theater writer Kohei Tsuka and the silent theater of Shogo Ota and Shakespeare and Racine. So I thought, if they are doing such a wild mix there must be someplace that I could fit in.

I had no wish at the time to enter one of the existing small theater groups. They have a unique style in which the company is led by a playwright who also does the directing. So, I thought that if I got into one of those groups and said I wanted to write and direct too, they probably wouldn’t let me. - I believe that the New Theater companies are organizations for professional theater people with literature departments and acting departments. What kinds of things do they teach you there?

-

I don’t know about the other companies, but En’s institute didn’t have specific curriculum or things that we were taught. During our first six months the actors did do voice training and other things together, but after that we went right into doing things like serving as assistants for the stage directors in actual productions and helped making the sets and props. Since I was also on the staff for productions put on by the people in the company’s training course, I would be making sets, helping out at the rehearsals, make more sets, and then going out drinking afterwards with my colleagues maybe until 3:00 in the morning. After that I would have to get up at 7:30 to open the studio for the trainees doing independent studies. So, I was basically living at the studio (laughs).

Because of that situation I had to teach myself about playwriting and directing. However, there was one director who was very knowledgeable about Chekhov named Takashi Sakuma who taught me a lot. For example, I am still aided by today by one bit of advice he gave me. That was to always think about what the characters who aren’t on stage at the moment are doing while they are not on stage. - If there is no training system for new directors at a professional theater companies like En, how are Japan’s directors educated in their craft?

- That is definitely a problem, I believe. Since they aren’t taught, it simply becomes a case of having people emerging who get the idea by themselves that something is new and interesting and it turns out to be new and interesting for other people as well. Because, in some cases, it just happens that something is right in sync with the social trends of the time and it becomes a hit for that reason alone.

- How did you come to start your company Gring?

-

From the beginning I wanted to do writing and directing, but in my second year with En’s institute I switched to the actors department with the aim of becoming an actor. When I failed the qualifying to remain in the company at the end of my fourth year, I still wanted very much to be an actor, but now without a place to work, for a while I ended up accepting acting parts here and there, wherever I was asked.

But, since I had originally intended to be a writer and director, wherever I worked I was always acting like a director and saying things I had no real right to say. I would do things like tell the direct, “That movement isn’t right.” (Laughs) I was the type of actor that I know I would never want to work with from the beginning if I were a director. (Laughs) Eventually nobody offered me parts anymore, and people told me, “If you are so full of opinions, you should be running your own company.” So, I decided to take their advice and I rented a studio. I was already 30 by that time. - Did you rent the studio before you started Gring?

- That’s right. Because Gring started out as a self-produced style of company where I would contact my former colleagues from En and get people who were free in terms of scheduling to work with me on a production. I had no money at the time and I had to work part-time as a cram-school teacher to just manage to get enough money together to stage our first three productions. The audience response wasn’t bad and so I proposed to our people that if we were going to continue doing production we should all pitch in and get together the capital to pay for them. That is the style we still use today.

- From the very start of Gring did you have the same style of play that you do now with, a number of people delivering lines at a good tempo in a tone of realism as a number of interwoven episodes develop?

- In fact, I had my eyes opened when I saw Hideki Noda’s— Sakura no Mori no Mankai no Shita and I wanted to write plays like that. But, when I tried and found that I couldn’t, the pressure of it all had me hyperventilating (laughs). I wrote until I had about 800 pages, but it wasn’t working. Still there was one part about three pages in length where a cram-school teacher is rambling on and on, and I thought I had written that rather well and enjoyed it. Sakuma-san read it and said “You may want to write like Hideki Noda, but you are not that kind of writer. This rambling style looks more interesting.” So, our first play became one about a group of cram-school teachers talking about doing something entertaining at the celebration party for their students who pass their college entrance exams.

- Your Gring plays seem to be the complete opposite of Noda’s plays from the standpoint of action of stillness and of fantasy and realism.

-

I have tried to analyze that difference myself. When I watch Noda’s plays, I get the feeling that he is the kind of person who thinks that running faster than others is beautiful—the fact that Noda was on the track team in high school may have something to do with this. So, his text runs, and it has to be running for those kinds of lines to come out. If people all stand on different grounds, then I think my ground, or perspective, is something like “fixed-point observation.”

My family used to run a delicatessen and box lunch business in Yokosuka for three generations. When they would make me sit at the cash register I would watch the working women and people from the neighborhood come in to buy something and say some really heavy things without batting an eyelash, like: “It looks like that coffee shop owner became a thief after he closed down his shop.” I think I have an almost inexhaustible stock of scenes like that where people say some serious things in the same tone of voice as when they are just chatting about meaningless everyday stuff. So, when I create that type of scene the words just pour out. That is what made me realize where my plays should be coming from.

It also happened that the first theater I rented was a pretty large one of the type that—and this gets back to what Mr. Ninagawa said to me that time (laughs)—if you stop the action and have someone deliver some long lines the audience is going to go to sleep. Or, to keep the action moving, I had to have people coming and going rapidly on stage. This is part of the reason why I got into the pattern of having seven or eight actors moving in and out and carrying on several different story lines at the same time. I believe that this writing style was born from my actual life experiences.

I’m also a type how easily gets tired of things, and if there is single story line playing on and on I tend to get tired of it. But, I have also worried that I should not be that way, so I think I will try writing a two-person play once. A play where one story played out by two actors takes one turn after another. The playwright Ryo Iwamatsu once advised me that it is a good experience to write a play for just two actors because you can’t make an hour and a half play with just two characters unless it is a pair that are in a very dramatic situation or relationship. - I have heard that you have a rather unique way of writing in which, when you get stuck you back to the beginning and start writing the play all over.

- Although I don’t know how everything will turn out, I do think about a general plot when I write. When I start writing there will be three or four story lines playing out at the same time, and I know what scene it will start from and I have an idea of how it will develop through the middle stages, but I don’t know how everything will end up. I write gradually, while thinking about what order the episodes should be told in and what movements of the characters should make to get me to the middle stage as I envision it. When I get stuck I go back to the lines at the top and look at them one line at a time to see where they stop. I ask myself at length what development will lead to what results. When I finally find a line that is problematic, I take out the laptop that I am writing on and erase all the lines after that one and save it with a new file name and begin rewriting from there. In this way it goes from the second draft to the third, and by the time it I finished I usually have about 40 drafts. Things come together between the 30th and 40th drafts. Once I get past the 30th I begin to feel that things are coming to a conclusion. It usually takes about a month and a half to write the first hour of the play, and the rest usually only takes about two days.

- Can’t you do something like writing the episodes and the characters’ appearances out on cards at the plot level and try rearranging them to work out the right flow and then write the whole thing when you have found the right order, for example?

- I have tried that, but it keeps ending up the way I originally had it in my head, so nothing interesting comes out of that process. I don’t feel like I’m making any breakthroughs, it becomes boring to write and the work dies. Not knowing how things will turn out while I’m writing is more stimulating and more fun.

- Until now, you have written plays set in places like a zoo that’s going out of business, or a hotel where members of a school trip are staying, or the back-stage of a strip joint, or a barber shop. Are there some kinds of places that you find especially appealing to write about?

-

Yes, there are. One is the kind of place that the playwright and director Oriza Hirata has called “semi-public places.” If it is a private space it is hard to have people making entrances and exits. So, it is easiest to write if it is a place that is half public and half private.

Also, in my case, there is usually a place right next to the setting that I want to write about. For example, in our first Gring production it was an empty lot next to the cram school. The cram school is the place where the students and teachers meet and it is the place where the students’ mothers come to complain; all the important events happen in the cram school. Then there is the empty lot next to it where the teachers practice their skit for the students’ acceptance party. The important meetings take place in the cram school and the people who don’t want to be involved in those confide their real thoughts in the empty lot.

In the case of the strip joint, what I really wanted to write about was what was happening on stage and, since it was a work that dealt with the Mito nuclear power plant accident, I wanted to write in the atmosphere of a town where the people have to live with a nuclear power plant. So, I chose the back-stage as the best place to show all of these elements came together from time to time. What is appealing is a place that is just a bit removed from the where the central events are occurring. Not completely removed but just a bit removed. - I hear that you always write in notes to the actors.

- Yes, that’s right. Since I wanted to be an actor myself, I want to do plays that make the actors look good. That is not a process of creating extensions of the innate individuality of the actor or trying to expand on it. The things I write for the actors are lines that I think would be interesting to have a particular actor say or actins that it would be interesting to see them do.

- I am also told that you have a particular play or book that you refer to when you write.

- That’s right, I always have one. It may be proof of how little story narrative there is in my plays (laughs). I think there is some resignation about the fact that I can never write something that is completely new. For example, my most recent work Niji (Rainbow) is built around Ibsen’s Ghosts . Ibsen’s is a story about syphilis, so I think things like making it contemporary by writing about HIV. For my play Kaizoku I thought about what would happen if I used the main male protagonist of A Streetcar Named Desire . The play Esperanto that I wrote in the Bungakuza Atelier was based on Mantaro Kubota’s Ohdera Gakko . The main reason for using modern drama works as my idea notes is that it is possible to take pure examples of human relationships out of the drama and rearrange them.

- It seems that all the characters that appear in your plays bring some kind of “grudge” to it. What kinds of “grudges” do you want to write about?

- I guess you can say that I have a desire to write about minorities. When you look at things from the perspective of a minority you find that what we think of as the accepted norms of society are not actually that normal. I want to write about the way people who are not in the majority see the world.

- What is interesting is that the “grudges” these minorities hold are never solved. And although they remain unsolved, the play ends with some slight flicker of hope.

- I am very happy to hear you say that. I think that probably reflects my view of the world. That is how I tend to look at the world. In other words, the problems that I encounter personally, for example, are seldom really resolved. It never happens that you wake up some day and suddenly your problems have been completely solved. Said from the opposite standpoint, if you sit in a place where a lot of different people from the real world are coming and going and look at the world from that perspective, you can encounter people there who will make you feel good that you had a chance to meet them, if only for a moment, and were able to hear them talk about something you will remember. That, I believe, is a very important thing. Your problems and worries may go on forever, but the people you meet today and share a moment with should help you get by.

- I imagine that you often have people say that for a young playwright you write a lot like the playwrights of the [older] New Theater generation. How do you feel about that?

- I think that is probably because my plays are about easy to understand situations, there is one clear role for each actor and the play develops in the form of a conversational drama. But, I don’t think that way. When I get one entertaining idea that I like, I believe that I can make it into a play. In the case of my latest work Niji (Rainbow), I had the idea of having a rain scene using real water, and then I thought that it would be moving to have light shine through a stained glass window and have it look like a rainbow (laughs). Although I can’t use huge amounts of water or have tons of flower pedals come showering down like Ninagawa does. My plays have stories that are ones that are built on a progression of very realistic, colloquial language, so you can’t suddenly do something big and dramatic at the end. In my play Innocent I wanted to have a shower of cherry blossom pedals at the end, but when I thought about it I realized that all I could really do was have a small flurry of pedals fall way off in the distance. Because the play to begin with is such a quiet one (laughs).

- Why are your plays always quiet ones?

-

I wonder why. When I got married I took my wife and went around to pay our respects to all of my relatives. We went to about 40 homes in all, and everywhere we went my relatives were the kinds of people who keep up a constant conversation, talking on and on. I guess that type of family character is what my memories are made of (laughs). No one makes grand pronouncements in a big voice, everyone just keeps talking normally. I guess it is in the blood. But, lately I am concerned about the fact that people say colloquial-language plays are becoming conservative. In other words, I’m questioning whether or not it is enough to just present the things I see in front of me in an easy to understand manner.

However, for our third Gring production I wrote a play called “Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow” about a National Defense Force soldier moving their base. At that time I thought that I could only write the kinds of plays I am writing now, and I also had the feeling that might be OK. One of the characters is a daughter who wants to write novels but finds that she can’t do it. She wants to write a grand-scale story but she can’t think of one. But, in the process of watching and listening to the small things happening around her, she gradually realizes it is only these small things that she is able to write about. That was clearly a case of me writing about my own feeling, and I thought at the time that if I pursued the writing of such details diligently and to the limit, something big and significant might be revealed on the other side. And that would be the same as giving people a truly grand-scale story. - For your 10th Gring production you have moved up to the Kinokuniya Hall, which is so-called mecca for Small Theater companies and hub of the New Theater. Why do you think your plays are so popular?

- I am not really sure that they are. The media writes about my works to a fair degree and I feel that my name has become known. If I really am being accepted by the audience, I think it must be because my “pursuit of detail” that I just mentioned is communicating to the audience and they feel those parts to be well written. I have come to feel lately that I really am a third-generation box-lunch maker. I can’t make sophisticated Kyoto kaiseki cuisine (laughs) and I can’t make creative new dishes. But, some may say that I make a good stewed tofu (laughs). I guess it’s the bloodline.

Go Aoki

Portraying the places where people with grudges come and go. The world of Go Aoki, a playwright shining light on the creases of the soul

Go Aoki

Born in 1967 in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Go Aoki graduated from the Literature department of Meiji University with a major in Drama. After being active with the “Theatrical group EN,” Aoki formed the theater company Gring in 1997. Since then, he writes and directs all the works for the company. Besides theater, he has co-written screenplays such as Chugakusei Nikki (Middle Schooler Diary) a (NHK screenplay) and IKKA (11th PFF Scholarship winner), and he also writes radio drama scripts.

Interviewer: Hirofumi Okano

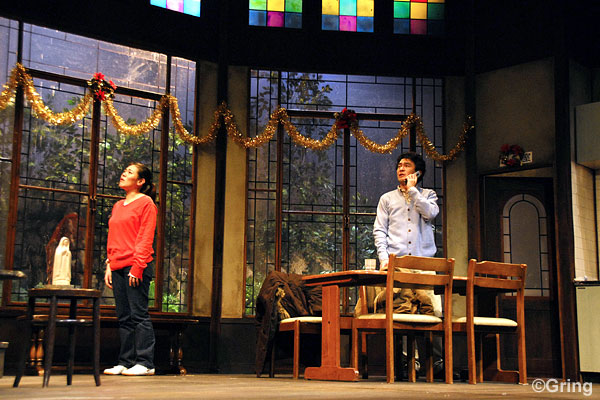

13th Gring production

Niji

(Rainbow)

Dec. 20-24, 2006 at Kinokuniya Hall

Written and directed by Go Aoki

Photo: Nobuyuki Kagamida

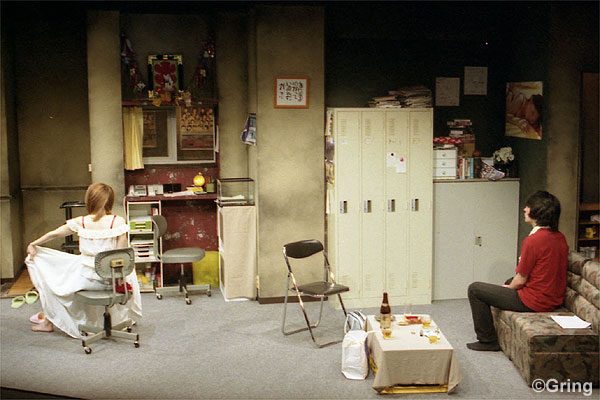

6th Gring production

Strip

Jul. 2-7, 2002 at Shimokitazawa Geki Theatre

Written and directed by Go Aoki

Photo: Hiroshi Kato

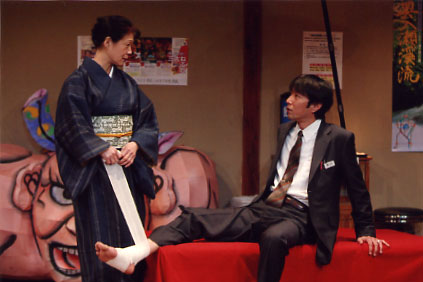

Bungaku-za Atelier no Kai produce

Esperanto – A Night on a Student Trip for Teachers

(at Bungaku-za Atelier, 2006)

Written by Go Aoki

Directed by Yoshisada Sakaguchi

Photo: Kenki Iida

9th Gring production

Kyuka

Jun. 25-Jul. 4, 2004 at Shimokitazawa Geki Theatre

Written and directed by Go Aoki

Photo: Naomasa Fukuda

10th Gring production

Strip

(re-staged)

Oct. 19-24, 2004 at THEATER TOPS

Written and directed by Go Aoki

Photo: Naomasa Fukuda

Related Tags