- Seeing your work, the label “action theater playwright” seems to fit perfectly. In your play Aterui (winner of the 47th Kishida Drama Award in 2002) about the battles between the Heian Period general Sakanoue Tamuramaro and the legendary warrior of the northeast, Aterui, and in your play Ashura-jo no Hitomi (Premiered 1987, performed by Kabuki actor Ichikawa Somegoro in two versions in 2003), where the supernatural-powered demon-exorcizing Onmyoji of the Heian Period named Abeno Seimei is used as a bi-player in a story of battles between demons and humans and love between men and women of supernatural powers, your plays unfold as romantic sagas involving fateful encounters between actual historical figures of a given period and fictitious characters and plots full of unexpected turns of events. And these stories invariably involve thrilling and violent action.

- It is true that I may be the only playwright around today that you might label an “action theater playwright.”

- How did you become involved in theater originally?

- It all started from a high school theater club. As a child I loved manga comics and when I went to high school I wanted to join a manga club. But, it turned out that the high school I went to didn’t have a manga club. Since you have to do some kind of club activity in school I looked around for the next most interesting thing and that was the theater club. In Fukuoka on the southern island of Kyushu where I grew up, there is a lot of emphasis placed on high school creative theater. So we used to go see regional drama contests and spend a lot of time making our own plays. That experience is what made me think that I could write plays too.

- What kinds of manga did you read then?

- I read all the popular manga weeklies for teenagers, like the Sunday and the Magazine . I also read the works of the great Japanese youth manga artists like Osamu Tezuka, Shotaro Ishinomori and Fujio Akatsuka. In particular, I read everything by Go Nagai, from his debut works and then when I was in middle school his work Devil Man (serial began in 1972 and became extremely popular as a Nagai masterpiece. The main character is a high school student named Fudomyo who becomes a devil-man with the heart of a human and the powers of a devil by becoming one with a devil in order to battle other devils) really struck me. I felt like I was maturing along with the development of the writer himself.

- How about the manga magazine Garo that Sampei Shirato and Yoshiharu Tsuge wrote for?

- Garo wasn’t like the youth manga s, so I didn’t like it. In short, I like the action stories of the youth manga and if you call me an “action theater playwright” it must be because that is the kind of action plays I write.

- You mean the kind of action stories with bright, outgoing, handsome and cool heroes like in the youth manga s rather than stories full of darker emotions like grudges and pathos? Did you write manga s yourself?

- I did. At university I was in the manga club, and when I got a job at the manga publishing company Futaba-sha (publisher of the Manga Action , also publishes numerous literary books) after university I took my original manga s to the job interview along with my persona vitae with the intention of being hired either as a manga artist or an editor.

- Did you not like theater as much as manga ?

-

I had only begun theater from a high school club. For whole time I like not only

manga

but also science fiction, because of “a sense of wonder” to be found in the words. It is something you don’t find in novels or other types of literature, it is the kind of fictional or slightly twisted idea or story line that grabs the readers and makes them wonder, “What is going on?”

In the latter half of the70s and early 80s, I believe there was that same kind of thing happening in the small-theater and underground theater works that were popular. I happened to see Juro Kara’s Jokyogekijo company’s performance of Hebihime-sama that they brought to Fukuoka in Kyushu to perform in an abandoned coal mine when I was in my first year of high school (1977) and I thought it was very interesting. I have had several fortunate experiences with theater like that. - The director of your Gekidan Shinkansen theater company, Hidenori Inoue, also began theater in a high school theater club in your hometown of Fukuoka. The first play he wrote was Momotaro Jigoku Emaki (a parody of the story of the demon-hunting boy Momotaro who was born from a peach [ momo ]. It is a play set to hard rock music and full of fight scenes.) It is a play that reminds us of what you are doing together with Shinkansen today.

- I saw that play in one of our high school drama contests and thought it was really interesting. I thought immediately that I had found someone who was thinking the same things as me, and it was a person who was one step ahead of me in terms of dramatization skills. I went to meet him and ask him if I could use his story to do another play, which is when I wrote a play that was a variation on his as the story of “the Demon-killing Demon.” He in return saw my play and liked it, and that is how we got to know each other. I have been doing the same type of plays based on Japanese legends ever since. Like the expression “As the boy, so the man” or “Once a playwright, always a playwright.” (laughs)

- What was the first play you ever wrote?

-

It was a parody on Tennessee Williams titled

The Case of the Crushed Manicure

. The next was a parody on Ionesco’s

The Lesson

in which the tutor kill the daughter only to have another daughter appear, one after another.

At first I thought drama of the absurd was “proper theater” and that is why I wrote things like that. Although I had my doubts as to why, at the time high school plays tended to be rated higher if they difficult to understand rather than ones with clear, easy to understand stories. After that I was strongly moved by the works of Kohei Tsuka, such as Atami Satsujin Jiken (the Atami Murder Case) and Shokyu Kakumei Koza – Hiryuden (A Beginner’s Course in Revolution – Hiryuden), and influenced by this I wrote a few plays using that kind of sophisticated rhetoric.

However, after I began doing plays with Inoue, I realized that this wasn’t me and that I should write things I could really believe in. When I asked myself what I believed in, the answer was “ manga -like action theater” or “movie-like action theater.” These were the things I had always been interested in, so I decided to try to bring manga -like or movie-like action to the stage. And that is what I have been doing ever since. - It is the kind of theater that the audience can see and understand, see and enjoy, isn’t it? What was your first play of this manga -like or movie-like style?

- Inoue came to me and said that he wanted to do a play to the title of Hoshi no Ninja (1986). It was a kind of samurai action drama with ninja and in the end a girl who fell from the stars flies back to her home in the stars on wings of light. I told him I liked the story and asked him to let me write the play. Since I liked the saga novels of Futaro Yamada, I added some of that flavor and once I tried that I amazed myself at how easily the script poured out of me. I thought, “This is the kind of work I should be writing.” Then, the next work I wrote after that was Ashura-jo no Hitomi .

- Ashura-jo no Hitomi has certainly had a long life as a popular work.

- Yes. It still hasn’t changed the essence of itself since then. It was Inoue’s idea to have a story of a woman whose love for someone turns her into a demon. Well, how can I explain to it. The work is something that came to me like a revelation from the gods. It is like a gift from the gods to me. In contrast, I think that Dokuro-jo no Shichinin (Seven Souls in the Skull Castle) is my diamond in the rough. It is a work that I have been cutting and polishing for 14 years since its premiere. I am grateful, though, that I have two such different works at the core of my repertoire, my oeuvre.

- In terms of its feeling, Dokuro-jo no Shichinin seems to be not as close to Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai as it is to the John Sturgess western film The Magnificent Seven based on the Kurosawa classic. It is a quick-paced action drama set in the Period of Warring States (16th century) in eastern Japan with a man who appears like a transformation of Oda Nobunaga (the leader of the Dokuro alliance, Temmaoh) fighting against outlaws typified by the main character, Sutenosuke. This play was done in two versions (both on 2004), Akadokuro starring Arata Furuta and Aodokoro starring the Kabuki actor Ichikawa Somegoro, and like Ashura-jo no Hitomi and Aterui , it is a play that seems so naturally suited for kabuki actors. Have you long had an interest in kabuki?

- No, I didn’t. But, reading books about Kabuki and researching it, I came to the conclusion that it was very close to what we were doing in Shinkansen. Like with Kabuki, we write for a specific actor, there will be jokes made during grand entrances and there will be audience-pleasing over-gesturing. So, if we are going to do period pieces, why not call it “Inoue Kabuki” (laughs). And now, the Inoue Kabuki we used to do in small theaters is being done in the big theaters with real Kabuki actors in the main roles. It just shows that it pays to continue doing what you do.

- What I find so interesting about your plays is the hypotheses they put forth. The work Susanoo—Kami no Tsurugi no Monogatari (1989), which made your reputation early on, takes its main theme from an ancient Japanese myth and tells a story of newcomers to the Japanese isles and the indigenous peoples building a nation, with some fictitious parts worked in. It is interesting the way you have actual historic figures meet fictitious characters at some specific place in a certain period of history and then the story develops from there, like a chemical reaction or catabolic effect. In Ashura-jo no Hitomi , for instance, you bring together the Heian Period (10th century) figure Abeno Seimei and the Edo Period (18th century) popular novelist Tsuruya Namboku.

- Since I was a child, I liked the romantic sagas of writers like Shiro Kunieda and Kyoji Shirai, although first it was Ryo Hanmura. In the 1990s I discovered Keiichiro Ryu, and his work was a real revelation for me. I got permission to do a play from his novel Yoshiwara Gomenjo (2005), because I was really moved by the way he depicted with such pride those people of the Yoshiwara red-light district who were normally discriminated against. I also like Futaro Yamada, but the underlying pessimism in his work goes against my nature somehow. Since I’m basically an optimist, I like to see people living with an optimistic approach to life. I feel that Yamaha and Ryu are like the front and back sides of a coin, the negative and the positive, and I personally am more attracted to the positive world of Ryu.

- One of the constant themes in your works is ethnic minorities as opposed to Ryu’s discriminated groups. Could it be that your ethnic groups are like the people that used to be called demons? Aterui is a story about the rulers of the day and those who will not submit—in other words it is a story of a battle with demons ( oni ). However, what makes your stories different is that they do not end with the pessimism of the resistance, the defiant minority.

- For me, the image of the demon ( oni ) is that of the indigenous peoples, but I don’t take them, the people who resist being conquered, as being in the right and therefore pitiable. I take a perspective in which it is a level playing ground with both sides—those in power and those resisting—being equal, and then I think about what kind of story I can develop from there. Of course, it is not enough for me that the story simply be interesting. That is where the battle between thematic integrity and entertainment value takes place.

- Whether they are people in power or those who resist that power, there is no interest unless they are characters with real blood flowing in their veins. In other words, I guess it must be a question of the (strong) presence of the characters depicted, whether they are fictitious or real.

- Yes, I think so. In the case of our Shinkansen company, we are involved in entertainment, so we have to provide works that the audience will feel satisfied after seeing. If a play ends with only a taste of pessimism remaining, what can you say? “Reality is hard.” That is a given. But we want people to come away from the theater saying, “That was really interesting, I enjoyed it.”

- Would it be all right to call you “an entertainment artisan?” Both you and Mr. Inoue seem to have this same stance, and I believe that is why Shinkansen has become such a popular theater company that draws large audiences.

- When we were young we did the kinds of riotous things that you can do when you are young, but if we forced ourselves to do that kind of thing now it would be empty and meaningless. In other words, both Inoue and I have continued to do what we feel to be true to ourselves, without clinging to the past. As a company playwright I will rewrite a work when there are new actors in the lead roles, and the sum total of all those efforts until now is our present state.

- When you think of Edo period playwrights, does Namboku come to mind for you before Chikamatsu.

- Yes, it is Namboku for me. When I wrote Ashura-jo no Hitomi , I read Yotsuya Kaidan first and found it very interesting. There was strength in the words and it made me realize that the old Japanese plays were more interesting than I had thought. But, I also wondered if young people in their twenties today would find such a play interesting if they went to the Kabuki-za Theater to see a performance of it. That led me to the conclusion that, since the text itself is interesting, we should do a play that would bring the spirit of the original text across in the present-day world. And, that is what Shinkansen is doing, I believe.

- Are there any particular things that you keep in mind when you are writing a play as an “action theater” work?

- I avoid writing in terms of concepts and try instead to express the story completely through the bodies of the individuals (actors). In order to do this you have to translate the tale into “people stories.” In the case of Aterui , I have to make it “Aterui’s story” in order for it to work for me. I believe it is a process of working down the themes into elements of the individuals’ feelings or the way they live and how the story develops through the clashing of these characters.

- So, in Aterui you have to think about the character of the individual Sakanoue Tamuramaro, for example?

- Yes. I believe that you can say that something you might call a dramatic theme can exist separate of the actual drama. But, what I am saying is shouldn’t the story come before the theme, and shouldn’t the bodies of the individuals who carry the story come first, too. In other words, you should first be concerned with depicting the characters standing on stage and let the theme that lies behind the story follow naturally as it will. In the case of action theater, isn’t really a question of if so-and-so fights so-and-so, which one will be the stronger? If you don’t make that a center of interest, the climax will not be exciting. The drama is created to achieve that aim. What I want to place importance on is the catharsis of the moment the stories that the characters carry as individuals are forced to clash on stage.

- And then, the characters speak words that carry weight based on those realities?

- That’s right. What’s more, it must not be in borrowed abstract expression that they carry in their heads but words that pour forth from that person’s body and the beliefs born of the conditions they find themselves in. With Aterui it will be Aterui words, with Ashura it will be Ashura words, their own personal words and no one else’s. Not abstract concepts or philosophical arguments.

- In your plays, the characters come forward and call themselves as names first, don’t they?

-

Yes, that’s right. It is the same with Bakin Takizawa, for example. In

Satomi Hakkenden

the characters are given names like

Shin

(truth),

Chu

(loyalty) and

Gi

(goodness) that have meanings in themselves. I am the same, and I spend a lot of time and thought on deciding the characters’ names. When the characters’ names are decided that also determines how they will be positioned. In other words, by the time the list of characters is complete about 60% of the play is complete. I think about the meaning the names carry and where they come from, so it takes me quite a lot of time to finalize the names. You could say that the reasons behind the names of my characters are another constant theme in my playwriting.

I think this is because the Japanese are a people of a country where words have spirits. The definite moves of the martial arts are the same way. We are quick to give a name to every move, like “ makkou karatakewari ” (“splitting the bamboo from straight-on”). We vie to create the coolest names and the names that sound strongest really do become strong. (laughs) - With its combination of hiragana, katakana and Chinese characters, Japanese is a very visual language. Just looking at the name of the main character in Ashura-jo no Hitomi , the swordsman Wakuraba Izumo, gives you an image of what kind of person he is. (laughs)

-

Another defining characteristic is the device of having things read as text in the stage notes. I also find a distinct rhythm to the dialogues.

Lately the notes and dialogues have gotten shorter, though. (laughs) There was a time in the past when I played with the text of the stage notes considerably. It is probably something fundamental for a writer, but first of all I want to write a “book” that the director and actors will find interesting when they read it. That is something I am always concerned with.

As for the dialogue, I want to write in a way that has a good rhythm for me. It is something I have only taught myself, but I basically write in a 5-syllable, 7-syllable meter and create a kind of fictional language that is different from the language of daily life. Therefore, I feel that the actors must have a fictional sensitivity and technique in order for it to work. - Do you visualize the scenes on the stage as pictures when you write?

- To some degree, I do have images in mind. But, Inoue is a director who brings such strong ability to construct the visual aspect of a play, so I defer to him in the visual realm. If I am an “action theater playwright,” then Inoue is an “action theater director.” I think it is a very rare talent that he has.

Kazuki Nakashima

Kazuki Nakashima’s spectacles of manga and Kabuki and romance legends

Kazuki Nakashima

Born in Fukuoka Pref. in1959, Kazuki Nakashima is active today primarily a theater scriptwriter. He has served as the company writer for theater company Gekidan Shinkansen since 1985. Since then he has primarily written play scripts that stress story narrative for the series of period action plays known as “Inoue Kabuki.”

His play Aterui starring Somegoro Ichikawa and Shinichi Tsutsumi (2003, Shinbashi Enbujo Theater) won the 47th Kishida Drama Award. In recent years, he has also been writing scripts actively for productions other than those of Shinkansen, such as Lady Zoro starring Hibiki Takumi and Oinari – Asakusa Ginko Monogatari starring Nobuko Miyamoto.

(Edited by Jun Kobori from an interview recorded in Shinjuku, Tokyo, Nov. 1, 2006; cooperation: Village Inc.)

Lord of the Lies

(Oboro no Mori ni Sumu Oni)

Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima

Director: Hidenori Inoue

Date: Jan. 2-27, 2007 (Shimbashi Enbujo, Tokyo)

Feb. 3-25 (Osaka Shochiku-za)

https://www.shochiku.co.jp/

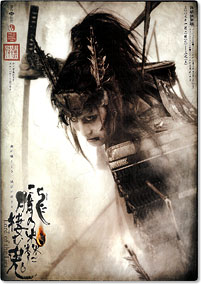

Ashurajo no Hitomi

1987 Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima Director: Hidenori Inoue © Village, Inc.

Hoshi no Ninja

1988 Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima Director: Hidenori Inoue © Village, Inc.

Susanoh

1989 Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima Director: Hidenori Inoue © Village, Inc.

Blood Gets in Your Eyes

(Ashurajo no Hitomi)

2000, 2003

Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima

sDirector: Hidenori Inoue

Cast: Somegoro Ichikawa, etc.

Associated with Gekidan Shinkansen and Village, Inc.

© Shochiku Co., Ltd.

Aterui

2002

Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima

Director: Hidenori Inoue

Cast: Somegoro Ichikawa, etc.

Associated with Gekidan Shinkansen and Village, Inc.

© Shochiku Co., Ltd.

Seven Souls in the Skull Castle (Dokurojo no Shichinin), Akadokuro version

2004 Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima Director: Hidenori Inoue Cast: Arata Furuta, etc. © Village, Inc.

Seven Souls in the Skull Castle (Dokurojo no Shichinin), Aodokuro version

2004 Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima Director: Hidenori Inoue Cast: Somegoro Ichikawa, etc. Associated with Gekidan Shinkansen and Village, Inc. © Shochiku Co., Ltd.

SHIROH

2004 Playwright: Kazuki Nakashima Director: Hidenori Inoue © Village, Inc

Related Tags