- Were you born in Nagoya?

- I was born in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture in 1964. It was the year the Tokyo Olympics was held and the year that the Shinkansen bullet train connected Tokyo and Nagoya. I grew up in the Imaike district of Chikusa-ku which is famous as a bar district and I went to the local Meijo University. In short, I’ve never lived outside of Nagoya.

- When did you begin working in theater?

-

In middle school and high school I was in the

Kendo

(Japanese sword fencing) club and absorbed in the martial arts. About the only theater I saw was the Yoshimoto comedies on TV. But, I did like people such as Hachiro Oka and Kanbi Fujiyama.

At college I was in the Business Department, so I had no direct relation to theater, but when a friend said he was going to enter the theater club at our school named Shishi, I went along with him. It turned out that there weren’t many people in the club and they were really anxious to get new members, so they welcomed me too, and I thought, “Why not?” (laughs). - What was your first production?

- I took part as an actor in a play based on a script that one of our upperclassmen had written. I don’t even remember what my part was, but the script was like a play on Kohei Tsuka’s Hiroshima ni Genbaku wo Otosu Hi (The Day the Atomic Bomb is Dropped on Hiroshima), or rather it was like a perfect copy of the script. Our upperclassman insisted that it was his own original, though (laughs). Anyway, that was my first experience with a play, so I thought, “This is theater!” There was the actor facing the audience in the pin spotlight and delivering long lines, and there were actors talking to each other in machine gun-like speed until the words got garbled. It was a perfect copy of a Tsuka play (laughs). I myself had never seen a Tsuka play, but his works were very influential in the college theater scene at the time.

- When did you begin to write your own original plays?

- It was in my second year of college. We had been invited to give a performance at a prison hospital and I wrote the script. I don’t even remember the name of it now. It was written with a Tsuka touch and at first they liked whatever we did, but it was a 3-hour performance and near the end that atmosphere in the place was getting pretty annoying (laughs). After that I became Shishi’s representative and I wrote a trilogy based on Japanese myths. The title was Takarajima -- Back Drop wa Kousurunda (Treasure Island -- this is how you do a back drop), and it was a really a preposterous story that brought in scenes with professional wrestling. I got the idea for the professional wrestling from a performance by the Minami Kawachi Banzai Ichiza theater group that I saw at the Nanatsudera Kyodo Studio. It was incredibly funny.

- When you began to work seriously as a playwright, were there any writers who influenced you especially?

-

Juichiro Takeuchi was definitely the biggest influence. I feel that I’m conscious of Takeuchi’s style at times when I am writing a script. I didn’t see his plays from his early period, but I saw the remakes of

Ano Oogarasu, Saemo

and

Kaki ni Akaku Saku Itsuka no Ano Ie

in the 1980s. I saw not only the Nagoya performances but also went to Tokyo to see the Atelier performances, too.

The first Takeuchi play I read was Shonen Kyojin . It’s the kind of work that keeps hitting the audience on the head like a baseball coach who makes his players practice their fielding endlessly. When I read it, I asked myself, “What is this stuff!” But when I saw the actual performance I was really moved by the strong presence of the actors Katsumi Kiba and Ryuichi Morikawa.

In the end, my plays during my college years were a combination of the writing style I borrowed from Takeuchi and the action I borrowed from the Minami Kawachi Banzai Ichiza theater performances. - Whose plays were you watching besides Takeuchi’s?

- Before college I had never been to any plays, but after I joined the theater club my upperclassmen told me I had to go see Juro Kara’s Jokyo Gekijo (Red Tent), so I did. There was a performance of Red Tent’s Shin Nito Monogatari at Shirakawa Park, so I went and stood in this long line of people on a rainy day. There was a gritty, underground feeling to it all and I remember feeling that if I entered that tent I might never leave it alive. There was something truly frightening about the atmosphere (laughs).

- Sounds like a Horror House (laughs).

- No. At a Horror House you know there is an exit at the end, but with the Red Tent, I wasn’t sure that I would ever get out (laughs). I was seated there right in the front row and suddenly Kara came out and shouted, “Hey, all you patients of the Shinjuku Asylum!” I didn’t know what was going on. When Kara and the actress Lee Reisen would come out on stage there would be calls from the audience of “yo, Kara” and “Lee!” like at a Kabuki performance. I don’t remember much about the contents of the play but I do remember how exciting it was. I can still see in my mind’s eye scenes like when an actress was trying to stuff some money in the napkin disposal box in the women’s toilet and couldn’t seem to get it in.

- I would like to back up a bit and ask you what it was that originally attracted you most about Takeuchi’s plays.

- One of the things that attracted me was his rhythm of the prose. That is for certain. When I read the plays of Takeuchi they entered my head and stayed there so naturally. Plays like Hisan na Senso (Tragic War) were so easy to understand and so fascinating. And, after seeing the play on stage and then reading the script again it was even more interesting because I could enjoy reading it with the pace and intonations of the actor Kiba. Originally I wanted to be an actor, so I was determined to enter Takeuchi’s theater company, Hihozerobankan. In my senior year of college I had already gotten a regular job offer, but I called Hihoreibankan and asked if they had any openings for new actors. I could tell from his voice that it was the actor Kiba who had answered the phone, and when he said no, they weren’t recruiting. Before I hung up, I said “You’re Mr. Kiba, aren’t you. Please keep up the good work.” Then I said to myself, “This is hopeless. I guess I’ll just have to take my job offer.” It was just at that time that I went to see the movie Keppu Rock directed by Sho Ryuzanji. There were a lot of actors from the small-theater movement there, and after listening to Ryuzanji and Takeshi Kawamura do a panel discussion after the movie, I decided that I couldn’t just go off and join the ranks of the business world (laughs).

- You started the theater group B-kyu Yugekitai in 1985, in your 5th year of college, right?

-

Yes. I turned down the job offer I had gotten and stayed in college for another year. My parents were really mad when I said I was going to do theater instead of getting a job. It is certainly natural that they should get mad. Anyway, I begged them to let me do theater, boldly making the claim that I would do a play that would draw an audience of 1,000 people and do a Tokyo performance by the time I was 25.

At the time, our Shishi group drew the largest audiences of any Nagoya college theater group and people told us that what we were doing was interesting, so I guess I had a bit of a swelled head. I was also determined to make our theater even more popular, and I actually believed that I was the one to change the Nagoya theater scene.

Then, in 1987 I won the Nagoya City Culture Promotion Award for my play Shimpan – Horonigaki wa Caramel no Aji (Umpire – Bittersweet Is the Taste of Caramel). I had happened to see a leaflet soliciting entries for the award contest and I thought that if I won a prize my parents might not be so opposed to my doing theater. So, I wrote Shimpan on a whim, just for the purpose of winning the prize. I had thought that it would be interesting to write something about a baseball umpire after seeing a leaflet for a one-man play by Kenichi Kato titled Shimpan . The idea for the play came to me one day while I was waiting to meet my girlfriend for a date. So I got out one of my college notebooks and wrote the whole thing down in about two hours while I was waiting. - Was there any particular baseball umpire that you used as your model?

- No. It all came from my imagination. I did like baseball and often went to games at that time.

- Did things change for you after winning the award?

- It was my mother who changed more than me. She wasn’t especially happy when I won the award, but when NHK called me afterwards and asked me to write a play for one of their radio programs, her attitude really changed. She had been dead set against me going into theater before that, but after the request came from NHK, she was suddenly very supportive, saying she wanted me to do my best in my theater work.

- Shimpan won acclaimed when it was performed as a solo play by Ben Izawa from the theater group of Sou Kitamura. And it was performed in an actual baseball park and broadcast on NHK.

- I’m really glad now that I wrote Shimpan . I was 23 at the time, and Sou Kitamura directed the Izawa production for me. He also told me to rewrite it as a dialog instead of a monologue. I learned so much from that experience.

- After Shimpan you began writing new plays for B-kyu Yugekitai. Were there any other writers besides Takeuchi who influenced you at that time?

- I am not the type that does a lot of reading. When Takeuchi wrote things about writers like Kafka and Kobo Abe, I would go and read their works, but that was about all. Of Kafka I read The Metamorphosis and The Judgment , and in Abe’s case, I liked his novels more than his plays. Abe lies with a consciousness of guilt and I like the way he goes into such detail about how to tell lies. I also like the grotesque images Abe uses, such as kaiware daikon sprouts suddenly coming out of one’s shins. And, I like the horror cartoonists Kazuo Umezu and Hideshi Hino.

- Are you not interested in writing novels? In the postscript of Nukegara you write that people who have something they want to write become novelists and people who have something they want to see become playwrights.

- There are some playwrights who also write novels, but after turning 30 I realized that I couldn’t write novels. I don’t have the vocabulary to be a novelist.

- Earlier you mentioned Sou Kitamura, who also bases himself in Nagoya. When did you begin seeing his plays?

-

I have been seeing his plays since his Suisei 86 period. I saw plays like

Goodbye

and

Banka RA Blues

, and I remember being really surprised by the actor Hiroshi Kanbe and the way he stutters through his lines. I also liked Kitamura’s other actors very much. But, as clear as the characters of the actors come out, I don’t feel that I was influenced at all by Kitamura’s writing style.

In my 4th year of college, One of the members in our Shishi group wanted to do a production of Kitamura’s play Hogiuta (Ode to Joy). But when I read the script and when I watched a video of Kenichi Kato acting it out, I still couldn’t really understand it, and I wasn’t really anxious to do that production at first. But, then I heard a tape of Kitamura directing T.P.O Shi-dan theater group in a production of Hogiuta , and I found that to be incredibly interesting. It was a legendary performance with Kentaro Yano, Senko Hida and Izo Okachi. I then I knew that I just had to direct this play, and I had to play the character Gesaku. So I ended up stealing the production from my fellow member (laughs) and staging it as an outdoor performance. - You are said to be the kind of playwright who writes to fit the character of the actor in a role. Kohei Tsuka, who influenced your early work, is said to be a playwright who values the individuality and character of the actors and works out the script by explaining the part to the actor verbally in rehearsal and then write down what comes out. Do you think that you were influenced by that?

- Rather than calling it Tsuka’s influence, I would honestly say that it was the natural outcome of having to write plays for the actors you have at hand in the company. I am not one who believes that the work (the written play) is something that exists before all else. I am the one who can’t write until I see the faces and the bodies of the actors. That is even true when I write a play for a company other than my own. So, I always have them introduce the actors to me first and get to know them as best I can before I can start to write.

- What is the most important aspect of the actor you look at?

- Their voices are the most important thing. After doing a preliminary workshop with the actors I may go out drinking with them and such, so that I can listen to their voices and observe the way they speak, their physiques and the gestures they use. I also look to see the things they respond with interest to. But, the most important thing of all is the voice. A person’s ability to be convincing is decided by their voice. Listening to their voices tells you the important things.

- When you were first working in theater, including your college theater days, you were writing, directing and acting. Lately you seem to have given up the directing.

- It has become increasingly hard for me to handle both the directing and the acting. An actor doesn’t have to think about the entire storyline and how one scene will carry over into the next. For the actor it is enough to think about how to create their own presence in the here and now of a scene, but the director has to be thinking about more than that. I got tired of seeing the director in myself that was forcing me to hold back as an actor. Since I want to keep writing and acting for a long time, I have asked Shogo Kamiya to do the directing for our company. But, when I write a play for another company and am not involved as an actor, I will do the directing.

- What is the appeal of acting for you?

-

Taking on the state of mind of a character. For example, in the role of a murder, taking on the state of mind where you are ready to kill. Of course, if the play is not going well, you do not always get into the desired state of mind.

Also, there is a completely different appeal when I am acting in one of my own plays and when I am an invited actor in someone else’s play. When I acted in a play by Atsushi Fukatsu, I couldn’t understand the part just by reading the script. But, during the course of the rehearsals that part I couldn’t understand naturally seemed to instill itself in my body. I like that strange feeling of not being yourself anymore. It doesn’t bother me at all. It is like enjoying the grinding of sand on your teeth when eating a clam that hasn’t been completely rinsed out. - Listening to you talk, it sounds like you are a person who is always trying to see yourself objectively to some degree. When you are writing, are you the type who finds the words pouring off the tip of the pen. In other words, the type whose pen seems to move by itself?

- When I am writing I get tired very quickly. If I write for an hour or two, I have to lie down then for about an hour. Then I get up and write for another two hours before I have to lie down again. It is a repetition of that. Day and night no longer exist. When I lie down to sleep I will dream and suddenly get a revelation in my dreams about the story. If I have just a little free time during the day I will use it for writing. Even when the writing is going well, I will stop to take a nap and rest. I believe that it is not good to be in a state where the writing is going too well and the pen is running on by itself. Maybe I am too much of a skeptic. My writing is always punctuated with naps (laughs).

- It seems that there are many writers who can’t write and the frustration builds and then all of a sudden the words come pouring out. So, what you describe seems rare. A napping writer (laughs). Perhaps that can be called a kind of objective writer. By the way, in your Kishida Award-winning play Nukegara , the protagonist deceased father sheds his skin repeatedly, getting younger each time. That idea was brilliant. How did you come by it?

-

The idea of a dead person coming back as a rejuvenated incarnation of themselves is an idea that many writers have used in the past. Kazuo Umezu used it in his manga

Again

, so it is not really new. In fact, when Bungaku-za asked me to write a new play for them it was just at a time when I was living with my father, who was battling with senility. He would go to the toilet at night and not come back for an hour or more. I would go and open the toilet door and of course there he would be. It was then that it occurred to me, “What if he shed a layer of himself like an insect, left it there in a wrinkled pile and came out a younger version of himself?” I quickly wrote the idea down and said to myself, this is going to work! [for a play] (laughs).

I think that part of the basis for the story may have come from an Umezu manga that I read some time ago. And the opening scene where the six shed skins of the father are all sleeping together comes in part from the first scene of Takeuchi’s Yoi-Machi-Gusa . That play begins with a scene of remembrance where a woman is sleeping under a tree. I had long wanted to do a play that started that way, and I thought it would be interesting if all of as sudden there were six fathers all sleeping together. - It seems that you are in fact quite a journeyman writer.

- Yes. I think I am a journeyman, a writer who works steadily at his craft. Another playwright in the Nagoya area, Tengai Amano of Shonen Oja-kan is someone I think of as a genius type, while I see myself as a journeyman type craftsman. I have had this feeling about myself for more than ten years now. It was at about the age of 30 that I started seeing myself that way, around the time that I came down with a duodenal ulcer. I realized that I wasn’t a genius, and I have followed the path of the craftsman ever since (laughs).

- Just being a skillful craftsman doesn’t win someone a Kishida Drama Award, though (laughs). I would like to ask you what the theme that you are most interested now is.

-

It is the theme of what morality is. That is what my new play

Puramoral

(Plastic Morals) our company will present in June is based on. I have a daughter who is just entering middle school and I am serving as the president of the PTA right now. As everyone knows, there have been an increasing number of incidents of “suspicious persons” appearing harassing children lately. But, when I go to the school wearing my usual worn-out denim jumpsuit, I must look like one of those “suspicious persons” (laughs). In fact, I have been mistaken for one in the past.

“Who is this strange guy?” You can’t know a person just by looking at them. If you meet someone for the first time and you have no information about them, it is in fact hard to tell what a human being is like. When a murderer is caught and you see them on TV, you often think, “How could such a serious-looking person do such a thing?” At other times you may think, “He looks like the kind of person who would do such a thing.” Like Ryunosuke Akutagawa wrote in his famous story Yabu no naka (In a Grove), people can look completely different to different people or when looked at in a different light. That is what I am interested in. We ask, “Who in fact are you?” - When a terrible incident happens and the commentators on TV are saying “How could a person do such a thing.” But, wouldn’t you say that human beings are unfathomable creatures to begin with?

- Yes, yes. By nature, there is no way to really know people, or what they will do. That is why most of the people in my plays don’t have names but designations like “Man 1” and “Man 2.” I do this because if I give a character a name like Mr. Kimura, the audience will accept him and have him imprinted in their minds as Mr. Kimura, and I don’t know if that is a good thing to allow. Because he has the name Mr. Kimura, is it all right to let him be known simply as Mr. Kimura. It is because this is a point that bothers me.

- When was it that you arrived at that kind of style as a playwright?

- It began in 1992, when B-kyu Yugekitai did the play Indojin wa Bronx e Ikitagatteiru (The Man from India Wants to Go to the Bronx) and Takeuchi directed it for us. He was ruthless in telling us the bad parts of the play and criticized everything, right down to the way the actors stood. That was an eye-opening experience for me in countless ways.

- Of the things the Mr. Takeuchi told you at that time, what left the deepest impression on you?

- He said “Show them from the beginning. Let the audience know the answer from the beginning.” So that is what I did with Nukegara too. He often told me, “If you think of something interesting, write it right away and make it into a play right away.”

- Your plays often begin with absurd or irrational situations, like Dokan (Earthenware Pipe), where a big earthenware pipe suddenly juts into a room and provides an opening into new worlds, or Kan-Kan Otoko (Kan-Kan Man) about a man whose job is collecting the bodies of people who have been hit by cars and killed. How do you feel about being called a playwright of the absurd?

- I can’t write unless I have one of these [strange] situations to start from. So I don’t think of it as absurdity, but I don’t mind be called that kind of playwright. It is like the eating of a clam and having the sand grind between your teeth that I mentioned earlier, I can’t start anything without an odd situation as the starting point.

- Your plays themselves unfold in the situations of everyday life. What is it that you find in everyday life that you want to make into the motif of a play?

- I find it very interesting when I get a glimpse of some “passion” that is hard for a third person to understand. For example, I have a friend who works in a police crime lab, and he says that when he sees a footprint he can tell you a lot about what kind of person left that print. Ever since he was a child he had a fascination with the bottoms of feet. Even with wild animals, it was only his footprints that he was interested in, and he could tell you what animal it was just from its footprints. I love to listen to the things people like that have to say.

- So, you are interested in people with unusual talents?

- Right. Especially people with talents in seemingly meaningless areas. For example, if I hear about a person who loves turtles and is obsessed with turtles, I start to imagine the world of the person and the turtle. Then I come up with a story like “Two Men Who Devote Their Lives to a Turtle That Has Grown So Large It Fills a Room” (laughs).

- Is it an attraction to the extremes to which such passions go? Or is it an attraction to the “existence” of the human beings themselves?

- That’s a good question. When I encounter a person with that kind of passion, I begin to look in my mind’s eye for potential distorted variations or developments. For example, in Kan-Kan Otoko there is a person who is staring fixated at the railroad tracks. I begin to develop it in a distorted way and soon I am asking, “What is that person? Is it the body of someone who has been hit by a train?” The imagination is given free rein and then I as how I relate to that imaginary world. I want to look at both that distorted world and we who are being pushed to the breaking point by that distorted world.

- So, the world of theater for you is the distorted things you create and yourself there dealing with them. Is that a correct analysis? You drive yourself to limit as you write, and the result is that you have to create a distorted world with seemingly absurd situations. But, always you find yourself there, too, dealing with it.

- Yes. That is a pretty good description.

Norihiko Tsukuda

A world of the imagination overflowing from the everyday- Playwright Norihiko Tsukuda

Norihiko Tsukuda

Norihiko Tsukuda was born in Nagoya in 1964. He is a playwright, director and actor who graduated from Meijo University. He is leader of the theater group B-kyu Yugekitai. Using outlandish situations, he creates a theater world that unfolds in a straight and rhythmical way peppered with comedy. He has won many prestigious awards, including the 3rd Nagoya City Culture Promotion Award for his play Shimpan–Horonigaki ha Caramel no Aji , the Playwright Association Outstanding New Playwright Award and the Yomiuri Theater Grand Prix Outstanding Play Award. The play Nukegara for which he won the 50th Kishida Drama Award was written for an Atelier performance at the Bungaku-za theater.

(Interview, editing: Jun Kobori/Cooperation: Katsumi Mochizuki. An interview recorded at the B-kyu Yugekitai studio in Nagoya, Aichi Pref., May 10, 2006)

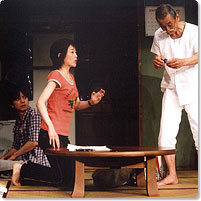

Bungaku-za Atelier no Kai

Nukegara

(at Bungaku-za Atelier, 2005)

Written by Norihiko Tsukuda

Directed by Yuko Matsumoto

Photo: Kenki Iida

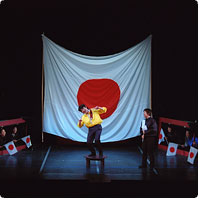

B-kyu Yugekitai

Two Hours to Self-destruction, Or How We Learned to Love the Doctor’s Distorted Love

(2005)

(c) B-kyu Yugekitai

Related Tags